This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 8 Autumn 2016.

The Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp (KMSKA) is currently undergoing renovation. It is a major operation. The majestic, iconic building at Leopold De Waelplaats dates from the late nineteenth century. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, it became apparent that numerous shortcomings would have to be addressed if the building could continue to be used responsibly as a museum: roofs were leaking, the indoor climate was less than ideal, galleries needed modernization, there was too little space, and so on. In 2003, the then Government Architect of Flanders announced a competition for a renovation design. The firm Claus and Kaan Architects (now Kaan Architects) was selected and the details of a master plan were worked out. In 2011, the KMSKA closed to the public, signaling the start of a major renovation and restoration project in which numerous parties are collaborating.1

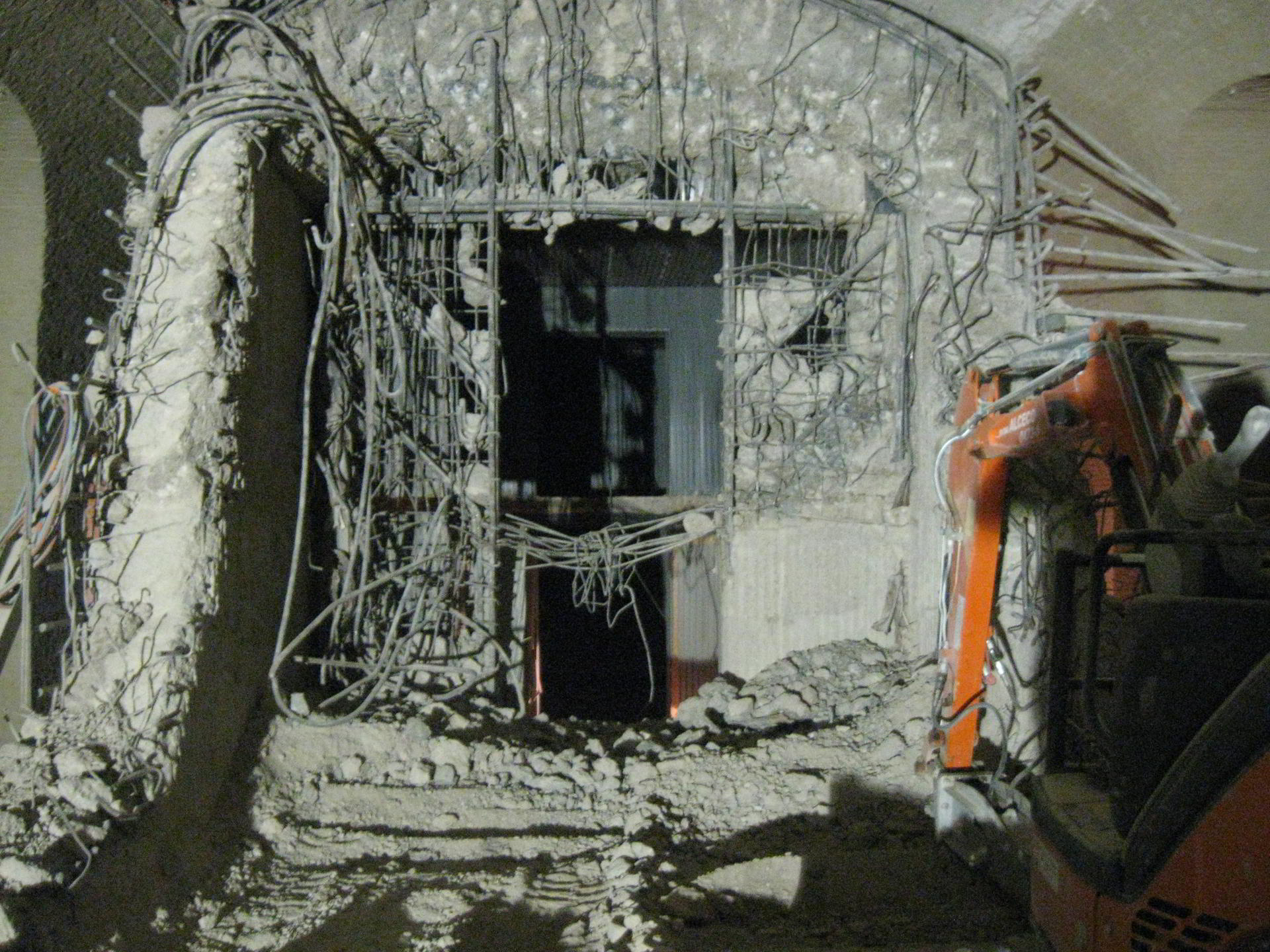

Demolition and Construction

The first phase involved the removal from the heart of the building of a reinforced concrete bunker (5.5 m. wide, 21 m. long and 9 m. high) that had been built in the 1950s, during the Cold War. The bunker had been built to protect the museum’s art in the event of a nuclear attack. Its walls were between 0.75 m and 1.5 m thick: 550 m³ of reinforced concrete, with a total weight of 2,150 tons. Removing the concrete was a completely manual operation and obviously very time-consuming. In the resulting space, a fully climate-controlled painting depot was built.

In the next phase, all the artworks were removed from the museum galleries and some of them stored in the new depot. This was necessary in the case of monumental paintings by Pieter Paul Rubens and others, which were too large to leave the museum. They were lowered on cables through openings in the depot ceiling and the floor of the gallery just above the depot – a system that had been constructed for this purpose when the museum was built and that remained in use over the decades (in both World Wars for instance). Another part of the art collection was transferred, along with the restoration studio, to a hired state-of-the-art new depot built outside the city. In addition, numerous artworks were moved on long-term loan to other institutions: the Cathedral and the Rockox House being the primary locations in Antwerp, along with international museums such as the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and The Metropolitan Museum in New York.

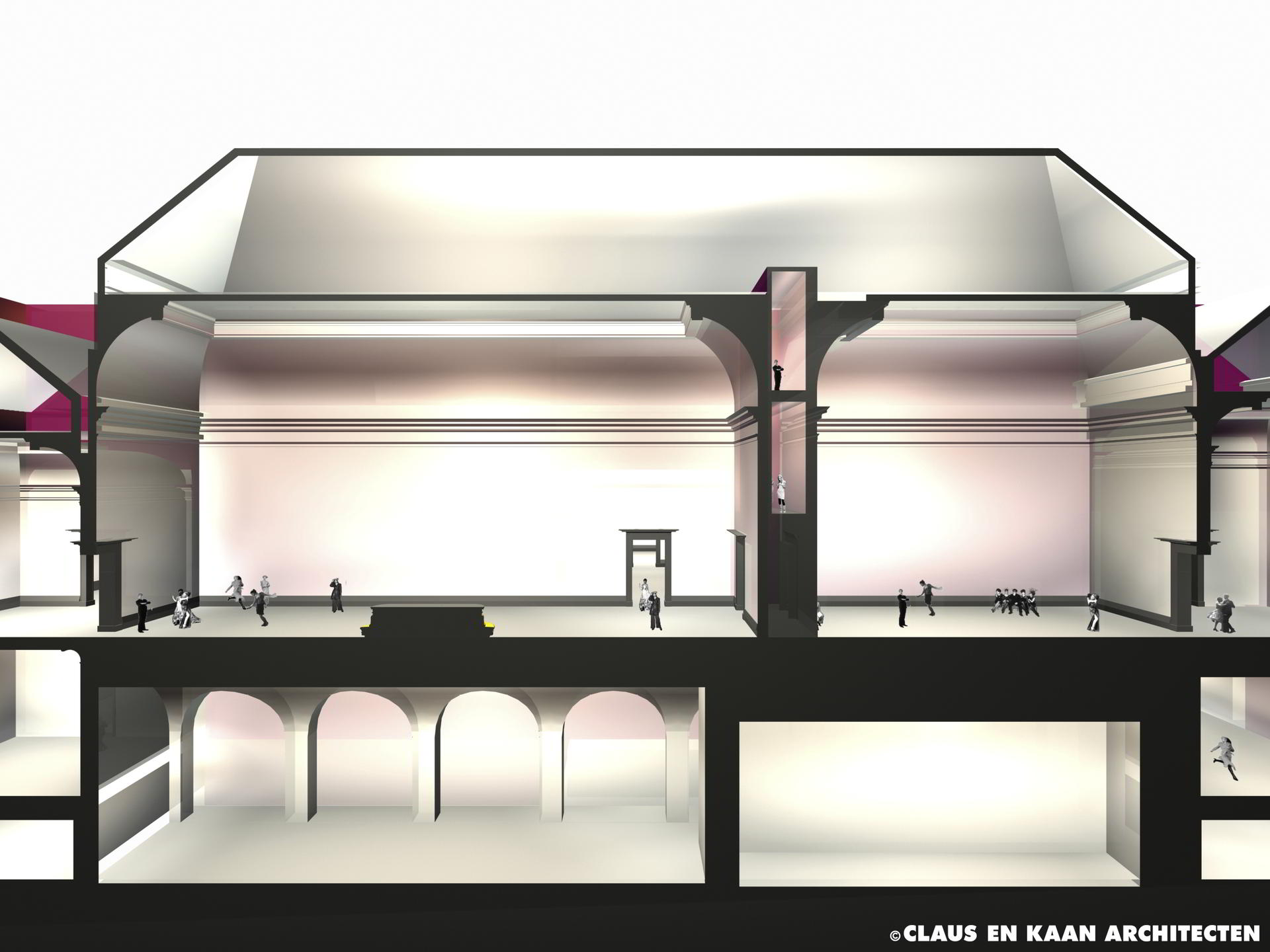

All in all, then, a great deal of work had to be done in the museum before the actual renovation and restoration of the exhibition rooms could even begin. The next phase started with the removal of extra rooms that had been added over the years, along with false ceilings, old technical equipments, and large quantities of asbestos. Doorways were bricked up and new connecting passages were constructed in the walls. In the meantime, from the outside it looked as if nothing was going on in the museum, until a large crane arrived. Set up in the space that had been cleared, it towered over the surrounding roofs. In the middle of the museum, along two sides of the central “Rubens and Van Dyck Galleries,” a four-story structure was built: 835,000 kg of steel, serving as the skeleton for the “vertical museum.” Lift shafts and new staircases were put in place. Above this structure, a completely new story was added.

3. Cross-section: on the left, in the center, and on the right the old building; at bottom center the internal depot area with above it the Rubens room flanked by the “vertical museum,” © Kaan Architects

“Feel, see, work”

The new KMSKA consists of three functional, related zones that provide congenial surroundings for old and new alike: “feel, see, work.” The “feel” section is the entrance to the museum, the block for public facilities including the visitors’ desk, ticket checks, and the museum’s main inner street. This provides access to the café, the shop, museum workshops, the auditorium, the library and reading room, the interactive information zone, and support functions. The “work” or “back office” area is at the rear of the building. The long foyer or “back street” here is the counterpart to the “main street” at the front. This area is not open to the public. It contains the staff entrance and leads to the offices and canteen, as well as providing access to the security department and diverse collection rooms and depots. The “see” area is the building’s central section, with all the rooms that are used for the collection. These are the old restored museum galleries and the new vertical museum. This part also includes an area not open to the public, with depots and rooms used for collection management and research.

4. Longitudinal section with the new passageway between the Rubens and Van Dyck rooms, connecting the two sides of the “vertical museum,” © Kaan Architects

The new museum is inserted, as it were, into the old one. The two are separated, although they are connected. This preserves the authenticity of the nineteenth-century rooms and other spaces and shows proper respect for the historic building. On the first floor, where the museum entrance is located, a large, long staircase in the new part of the building leads directly to the fourth floor. A third floor has also been added. This consists of three exhibition areas, two of them on the north and one on the south side. These are connected by a newly-constructed, invisible passage between the Rubens and Van Dyck galleries (the latter having been shortened by 2.9 m for the purpose). The vertical museum contains mezzanines allowing daylight to stream down into the galleries below and enabling visitors looking up or down to take in several stories at once.

All in all, with this renovation the KMSKA will acquire 40% additional exhibition space. The operation increases the number of rooms from 37 to 50, with a total exhibition surface area of 7,400 square meters.

Old and New Exhibition Spaces

The most important factor in museum architecture, of course, is ensuring that the paintings and other artworks can be displayed to the best possible effect in the different exhibition spaces. The new KMSKA will be architecturally eclectic, with its new hybrid of classical nineteenth-century rooms and a sleek twenty-first-century section. The rooms in the old part are 5.5, 7 and 12 meters in height, while the new ones range from 3 to 14 meters in height. Conspicuously large volumes. It is a big challenge to decide which works can be hung where and how they can best be combined. Furthermore, arranging the circulation of visitors around the building poses problems of its own. On the second floor, with the Rubens and Van Dyck galleries, there is none of the new architecture to be seen. The rooms have vertical and horizontal axes: it is here that the art dating from the fourteenth to nineteenth centuries is displayed. The KMSKA’s collection (totaling over 8,000 artworks) dates from the fourteenth to the late twentieth century. Although the center of gravity lies squarely with work by Flemish and Belgian artists, the museum also possesses an important and varied collection of artworks by international masters. The new arrangement will be based on themes. This means that the Old Masters will not be displayed according to century or “school.” Works will be grouped together on the basis of universal themes such as “mother and child,” “suffering,” “evil,” “power,” “morality,” and so on. The theme “body,” rather than focusing solely on portraits, will include works that highlight how the body is experienced and how it is viewed. Still lifes and landscapes – genres of which the KMSKA possesses an extremely rich collection – as well as sculptures, will also naturally receive the attention and space they deserve. Within the diverse themes, connections will at times be demonstrated between older and twentieth-century works. This will display the museum’s splendid collection from a fresh new angle and delight its visitors.

For decades, the painting depot and the restoration studio were located in the front section of the museum, which was closed to the public. The renovation reinstates the original route around the museum. The monumental rooms, with their stately columns, will again become a “salon” assigned to nineteenth-century art: the Academy painters, pleinairists, and naturalists. The restoration studio will now be located in the rear of the building, and visitors will be able to watch the conservators at work from the adjacent passage. The studio will be beside an “activities area” that will be incorporated into the visitors’ standard route.

The vertical museum will include separate rooms on the first floor for the James Ensor collection – the largest in the world, with 37 paintings and over 600 drawings. The work of Rik Wouters will also be displayed separately – in one of the smaller rooms on the third floor, where there will also be a print room and a gallery for small scale twentieth-century sculpture and changing presentations. The twentieth-century art collection will be displayed – under the headings “light,” “color,” and “form” – on the first and fourth floors.

In devising the “way-finding” around the museum, we focus both on the easiest route around the displays for visitors as well as on the most responsible routes for transporting the artworks to their exhibition places. A study of these factors revealed that the nineteenth-century rooms on the first floor are the most suitable for temporary exhibitions, since these three sections allow for both small and large exhibitions, besides which they are easily accessible. The exhibition plan for 2019 to 2024 is currently being prepared. The size and content of the exhibitions, as well as the type of show (monograph, thematic, etc.) will be considered and the changing displays reviewed. These decisions will naturally take into account the capacity of the rooms and realistic scheduling, including matters of logistics. It is a challenge to imagine how all this will work when we are not yet entirely accustomed to the building itself.

Please be Patient

It may be closed, but the KMSKA still dominates Antwerp’s southern district. Passers-by see a building and its gardens wrapped in banners and a huge crane towering over the roofs. When the museum reopens in 2019 it will be as an open house for art, a high-profile international scholarly institution that aspires to an active role in society, a creative hub in a network of cultural actors.

In the meantime, you are welcome to visit the website www.hetnieuwemuseum.be, where you can follow the progress of the renovation work as described above. You can also view the artworks can be viewed in diverse locations around Belgium and elsewhere (see exhibitions at www.kmska.be).

Elsje Janssen is Director of Collections at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp. She has been a member of CODART since 2011.

Notes

1 The renovation project was commissioned by the Vlaamse Overheid – Departement Cultuur, Jeugd, Sport en media (Culture, Youth, Sports and Media Department of the Government of Flanders) – Stafdienst Infrastructuur (Infrastructure Executive), Fonds Infrastructuur (Infrastructure Fund); responsibility resides with Het Facilitair Bedrijf – Afdeling Bouwprojecten (Services Company, Building Projects Unit); the architect Dikkie Scipio is assisted by the Bureau Bouwtechniek (Construction Technology Bureau) and other research offices (stability, technology, restoration); the contractor is Artes Roegiers.