In June, the exhibition Old Masters from Kyiv in The Hague opened at Museum Bredius in The Hague. The exhibition was prompted by Abraham Bredius’ visit in 1897 to Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko in Kyiv, whose collection forms the core of The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts. In Bredius’s notebooks, temporarily on loan from the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, the then director of the Mauritshuis gives a detailed account of primarily the Dutch and Flemish paintings he saw, his field of expertise. The exhibition is accompanied by a free visitor’s guide (in Dutch, English and Ukrainian) with more information about Bredius, his trip to Kyiv, the Khanenkos and the history of their collection, as well as the works on display. Following the close collaboration, Suzanne Laemers, curator of early Netherlandish Painting at the RKD and co-curator of the exhibition, asked Yuliia Vaganova, director general of The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, a number of questions about the consequences of war.

Fig. 1. Interior of the mansion of Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko on the then-named Oleksiivska Street in Kyiv, before 1917

What did the full-scale invasion mean for The Khanenko Museum and its staff, both practically and emotionally?

“What would your first thoughts be? You wake up to explosions, check your phone, and read the unthinkable: war has begun. Would you immediately accept that your life will never be the same? Or would you try to convince yourself, just for a bit, “No, no — this is some terrible mistake”? If we could ask the museum itself, it might say: “Oh, not again…” Because it’s been through this before: World War I, Soviet-era collection raids, World War II. It remembers Bolshevik artillery shelling Kyiv in 1918, explosions just a block away. Then came the Nazi air raids in 1941 — they shattered the windows. And in October 2022, a Russian missile strike did it again. Same windows.

“The museum probably hoped this kind of thing was a thing of the past. Humanity, after all, had made that noble promise: never again. Maybe the museum believed we’d keep it. As for the team, our minds did a very human thing: they protected us. We just couldn’t wrap our heads around a full-blown catastrophe. Or maybe we were too scared to. We didn’t think civilians would be bombed. Why? History wasn’t exactly reassuring. But still — denial is easier than panic. Yet, on 24 February 2022, almost the whole team showed up. We started conserving the collection. Many of us made the impossible choice: stay with our families and parents, or stay with the museum.

“Biggest lesson? When it comes to the museum, it’s on us. There’s no magical rescue team with a checklist. Every decision — from moving a painting to reinforcing a window — was ours.”

In the same year, the museum was also damaged by a missile attack. How severe was the damage of the missile attack in October 2022 and what is the current state of the building?

“This was one of the first attacks in Kyiv’s city center. At exactly 8:20 in the morning — our internal security cameras caught it — a blast shattered every window on the facade and part of the ceiling. For days, we carried out kilograms of glass. Part of it became a treasure – we put it in brooches and give them to special people as decoration. Part of it was used by artists for a new type of postcards. Thanks to friends and partners, we had plywood up the same day. Within a week, we added insulation to help the building survive winter — keeping temperature and humidity stable. Today repairs are nearly done. New windows, new roof. With help from the city, WMF, CER, UNESCO and others, the damaged historic doors were replaced and the originals sent for restoration. What’s left to repair is the facade and making the building more accessible, which will come with the future reconstruction phase. We dream to build a new block nearby.”

Fig. 3. Jacques Jordaens (1593-1678), Amor and Psyche, ca. 1650/55

The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, Kyiv

How is the museum trying to fulfill its function now that it is forced to store its collection elsewhere?

“In March 2022, Ukrainian writer Andriy Lyubka wrote that now “everything has been simplified to the very essence of things.” We asked ourselves: what is a museum for? Answer: to serve society. That’s it. That’s our compass. So, what do you do at the Khanenko Museum when you can’t show the collection? You tell stories. You hold on to memory — of the building, the founders, the artworks, the people who loved and worked here. Memory is glue. Without it, we risk forgetting who we are. You become a place of care. Since May 2022, Kyiv residents have been coming to our courtyard for coffee, homemade pastries, and packing lessons — the how-to-save-your-porcelain-during-airstrikes kind.

“You redirect energy. Jamala, a famous Ukrainian singer, raised some funds to fix part of our windows, but we re-directed the money to support snipers instead. Sometimes fixing broken windows means getting to the root of the problem. We gave teens space to write, speak, and scream about their feelings. We even hosted a blood drive — because one day, we realized the most important thing people could give at the museum… was literally themselves. On this day you could donate your blood for injured soldiers, civilians, children after shelling. That’s what we mean by going back to the essence. Maybe that’s why we received the CIMAM Award for Outstanding Museum Practices — even though we don’t fit the usual mold of a contemporary art museum.”

Can you tell something about the various projects with other parties and what they mean for The Khanenko Museum?

“In March 2022, our museum became empty, but not void. A strange, echoing emptiness — but one that made room for new meaning. To hear these new meanings, we had to try things we’d never done before. Stedelijk Museum Schiedam came to my mind — how creative the team and director Deirdre Carasso fiercely defended their museum’s right to exist, using unconventional forms of expression. Thank you, colleagues, for this — it helps us now.

“In the summer of 2022 we started working with our super-energized colleagues in Kharkiv while Kyiv was still frozen in fear. We launched Toy Soldiers. Invasion, a project with artist Oleh Kalashnyk. We created a project with Opera Aperta — a contemporary opera that filled the entire museum. For our team it was the very experience of contemplating how a musical work is created in the galleries. We used to work only with ‘dead’ Old Masters and now switched to making projects with contemporary artists. Our current storytelling is always connected with the museum collection and its history. Artists who had helped us during the first days of the invasion and debated with us about what to save first from the museum later created the project Meanwhile at Khanenko House.

“And thanks to the courage and support of Willem Jan Hoogsteder, we co-created the exhibition The Hague–Kyiv, which featured 31 paintings from the Hague School from his private collection alongside 11 Ukrainian paintings from the Ponamarchuk family collection in Kyiv. Piet Gispen’s photographs of modern The Hague rounded it all out. It was the first international exhibition of nineteenth-century European art at the museum since the full-scale invasion. This helped us deepen ties with private collectors and rediscover the historic links between Abraham Bredius and the Khanenkos.

“Each project is another mirror: Who are we now? Who are we becoming? We’ve worked with the Lithuanian National Museum of Art, the Royal Castle in Warsaw, the National Museum in Poznan, the Louvre and Louvre-Lens, Museum Schnütgen in Cologne, TU Dortmund University, and Villa Liebermann Museum in Berlin. Each collaboration was rooted in shared stories — of artworks and collections alike.”

Fig. 5. Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Scaldis, Cybele and Antwerpia, ca. 1615

The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, Kyiv

Would the museum like to realize more such collaborations and why?

“Every international project is a conversation about what we hold in common. It’s a chance to share experience and to speak about the strength of museums: how they can be sources of support, and teach resistance in their own way. We hope that our museum colleagues around the world will occasionally look away from blockbuster shows and ask themselves: What is the core purpose of a museum? What can we do for humanity, if we claim to serve it? We can talk about justice. Counter historical manipulation. Stand against war. These may not be the most appealing topics, and sure, people would rather look at flowers. But hard topics don’t go away on their own. Better to stay ahead of them. Some museums are doing this. I visited an exhibition at the Mauritshuis about the life of the museum during World War II. We could create a mirror project: what’s happening in Ukraine right now. Nothing has changed. The same labeling practices. The same propaganda exhibitions in occupied territories. It’s all happening again. After 15 minutes in that show, I realized I could give a full tour. The parallels were that strong.

“Every collaboration with Ukrainian artists and partners deepens our knowledge of our communities and their superpowers. It builds new, meaningful connections. And it affirms our right to choose not to flee, but to stay, to work here, in our own cities and country. That’s why support for these kinds of projects, on-site, is so valuable to us.

“Right now, there’s no truly safe place for our collections in Ukraine. So the possibility for international partners to temporarily shelter artworks and help share our collections with the world would be a huge support — and we’re always on the lookout for such opportunities. For us, protecting a collection doesn’t mean locking it away in a box. It means keeping it alive — showing it in safe spaces, using it, speaking through it. After all, we preserve not only Ukrainian art. The Khanenko Museum, for example, holds masterpieces of world heritage — artworks that are also witnesses to your cultures and identities. And when they interact with Ukrainian culture, they spark new ideas and concepts. Since we can’t present these works ourselves at the moment, we’d be genuinely happy if others could enjoy them in the meantime.”

-

Fig. 6. Follower of Rembrandt van Rijn, Young Woman

The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, Kyiv

-

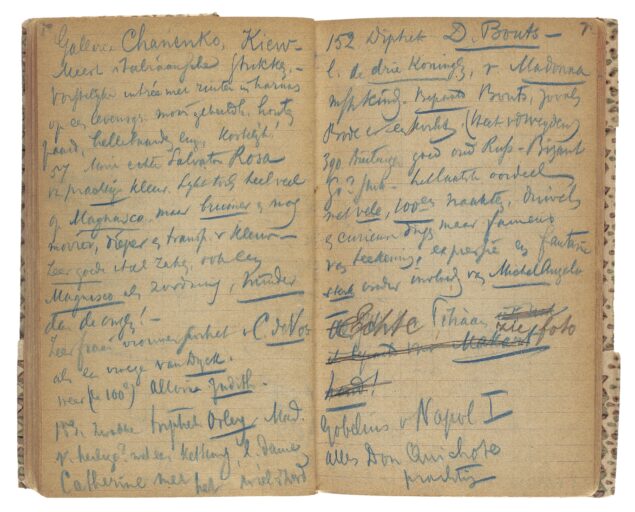

Fig. 7. One of the notebooks Abraham Bredius carried with him during his trip through Eastern Europe in 1897

RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague

How extraordinary was it to learn that Abraham Bredius had visited the mansion of Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko in 1897 and made notes of his impressions of the collection? What new insights did that give the Khanenko Museum?

“Our collaboration with Museum Bredius and the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History is a natural continuation of the cultural ties between our countries and the great patrons who laid the foundations of their collections at the end of the nineteenth century. In times of war, the exhibition Old Masters from Kyiv in The Hague takes on a special meaning: it shows that cooperation, dialogue, and the preservation of cultural heritage help us endure and build bridges between the past and the present. We are sincerely grateful to our Dutch partners for their trust and our shared belief in the power of culture.”

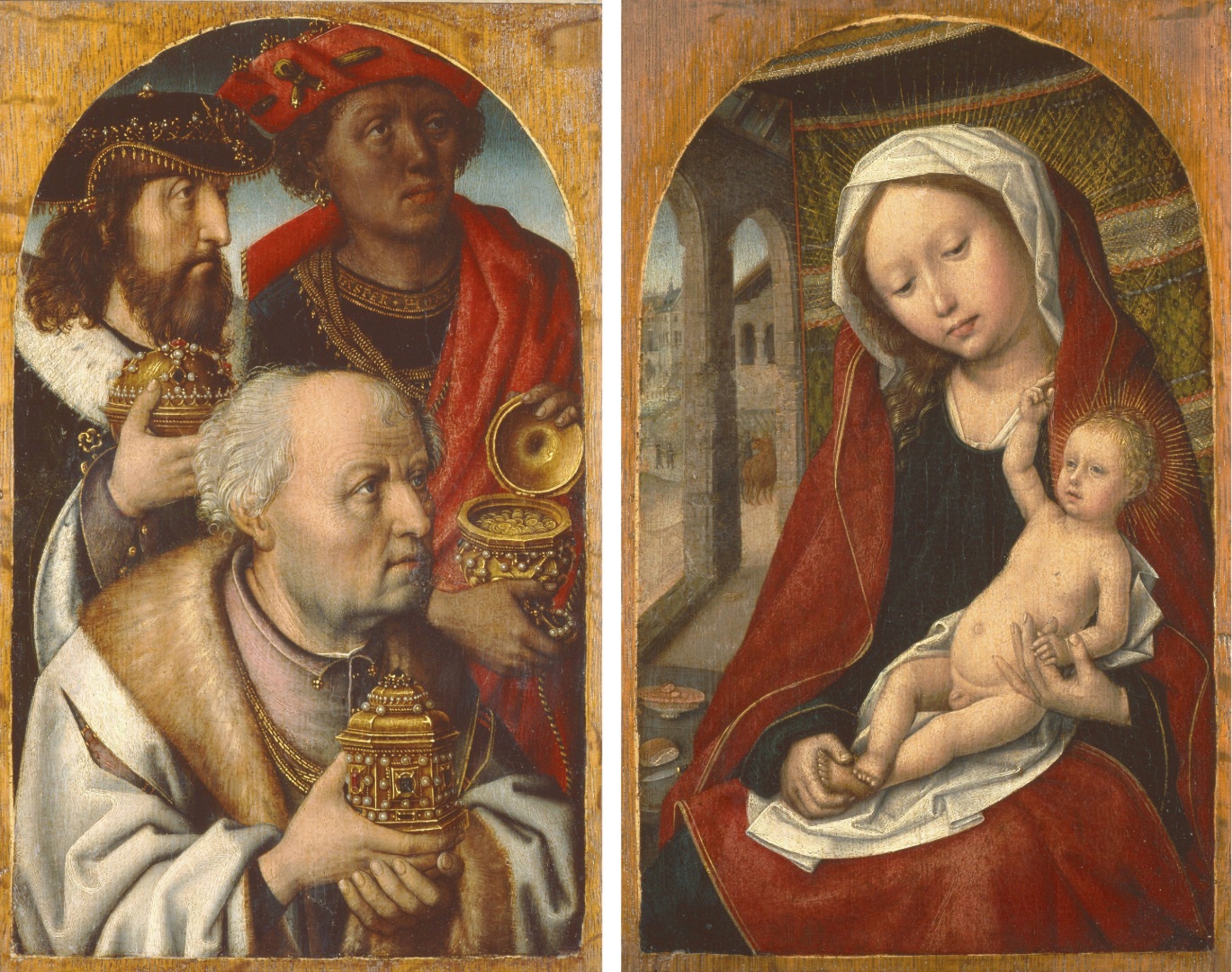

Fig. 8. Master of the Khanenko Adoration, Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1490

The Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko National Museum of Arts, Kyiv

Which hopes do you have for the future?

“In the very short term: we’d love to sleep through the night without air raid sirens. Just once or twice a week, maybe? That would be dreamy. Literally. Because, you know, it’s hard to concentrate on museum strategy when you’ve had two hours of sleep and spent the night in a hallway with your cat, a flashlight, and your laptop. In the next year: for Ukraine to win. And in the longer run: for us all to recover. To stay kind, curious, joyful — not hardened by pain. To be strong, but not numb.”

Is there anything else you would like to add?

“This may sound completely irrational and not at all safe, but… we’d love for you to visit. Come see us. It will change you.”

Suzanne Laemers is Curator of Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Painting at the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History. She has been an associate member of CODART since 2007. Yuliia Vaganova is the director of the Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko Museum of Arts in Kyiv. The exhibition Old Masters from Kyiv in The Hague is on view at Museum Bredius until 12 December 2025.