Sixty-five paintings that usually hang in the Picture Gallery at Buckingham Palace and are widely acknowledged to be among the highlights of the Royal Collection will be brought together in a gallery exhibition for the first time. In Masterpieces from Buckingham Palace, spectacular works by artists such as Titian, Rembrandt, Vermeer, van Dyck and Canaletto can be enjoyed ‘close up’, and visitors will be encouraged to consider the artists’ intentions, why the paintings were highly prized in their day and why we would now consider these works to be ‘masterpieces’.

The exhibition has been made possible by the removal of the paintings from the Picture Gallery, one of the State Rooms at Buckingham Palace, to prepare for the next phase of the ‘Reservicing Programme’. This major ten-year project will overhaul the Palace’s essential services, including lead pipes and aging electrical wiring and boilers, to ensure the building is fit for the future as an official residence of the Sovereign and a national asset for generations to come.

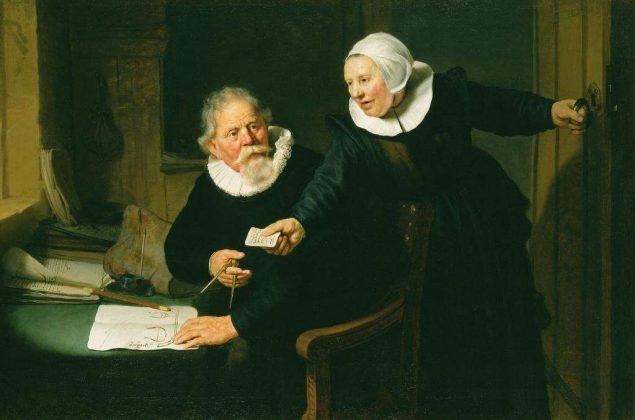

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), “The Shipbuilder and His Wife”: Jan Rijcksen (1560/2-1637) and His Wife, Griet Jans, 1633

© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2014

One of the themes explored in the exhibition is the artists’ masterly use of paint. In Rubens’ Self-Portrait, 1623, thinly applied pigment brilliantly conveys the translucent quality of flesh, and blue and red highlights help create the impression of three dimensions. The furrowed brows, weather-beaten cheeks and wrinkled skin of Griet Jans and Jan Rijcksen in Rembrandt’s The Shipbuilder and his Wife, 1633, appear to have been sculpted out of paint, vein by vein. Frans Hals’ serrated brushstrokes on the right-hand sleeve of his Portrait of a Man, 1630, convey the shimmering effect of light on luxurious black satin. In Judith with the Head of Holofernes by Cristofano Allori, 1613, Judith’s faultless complexion and golden costume contrast with the grotesquerie of her victim’s severed head.

Several of the paintings have a mesmerizing realism, in many cases enhanced by the use of illusionistic design. Compositional devices such as the false window ledges in Rembrandt’s Agatha Bas, 1641, The Grocer’s Shop by Gerrit Dou, 1672, and Jan Steen’s A Woman at her Toilet, 1663, project people, objects and scenes into the viewer’s space. In Lorenzo Lotto’s Portrait of Andrea Odoni, 1527, the sitter appears to reach out of the painting, offering the statue of Diana to the observer. In ‘The Music Lesson’, early 1660s, the impression of an ‘encountered’ scene belies Johannes Vermeer’s carefully constructed composition.

In other works, atmosphere, rather than precise detail, brings people and places to life. The rowers heaving their oars in Canaletto’s The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day, ca.1733–4, transport the viewer to the lively festival celebrating Venice’s marriage to the sea. Idleness, drunkenness and lechery are exposed in Jan Steen’s Interior of a Tavern, with Cardplayers and a Violin Player, ca.1665, in contrast to David Teniers the Younger’s Fishermen on the Sea Shore, ca.1638, which conveys the realities of hard work. The hazy, diffused light in Claude Lorrain’s Harbour Scene at Sunset, 1643, seems to permeate every corner of the painting and transports the viewer into the heart of the imagined place.

Atmosphere is also projected through narrative. In Cardplayers in a Sunlit Room by Pieter de Hooch, 1658, the furtive eye contact between the two men at the table suggests that they might be scamming the woman between them. The sitter in Titian’s Jacopo Sannazaro, ca.1514, appears reflective, while the subject of Domenico Fetti’s Vincenzo Avogadro, 1620, is hauntingly pious.

While many works present the viewer with a ‘real’ world, others are imbued with an idealism drawn from the study of classical art, as seen in Parmigianino’s Pallas Athene, ca.1535, and Guido Reni’s Cleopatra with the Asp, ca.1628. More direct quotations from the Antique are found in van Dyck’s Christ Healing the Paralytic, 1618–19, and in Titian’s Madonna and Child with Tobias and the Angel, ca.1537.

Masterpieces from Buckingham Palace will be accompanied by a display charting the evolution of the Palace’s Picture Gallery after the acquisition of Buckingham House by George III and Queen Charlotte in 1762. Their picture arrangements, a mix of Dutch, Flemish and Italian works, continue to influence the hang in the Picture Gallery to this day. Thirty-four of the paintings in the exhibition were acquired by their son, George IV, who commissioned the architect John Nash to transform Buckingham House into the principal royal palace in the 1820s. Part of Nash’s scheme was the creation of the Picture Gallery to show off George IV’s collection of paintings.