The past several years have seen a surge of interest at museums in women artists and women in the art world. It is now five years since the Rijksmuseum launched the project Women of the Rijksmuseum, which aims to redress the gender balance in the collection and the stories told by the museum. This “catch-up” is more than justified, but how can this increased attention for women be structurally embedded in museum practice?

Hanna Klarenbeek, curator at Het Loo Palace, interviewed Jenny Reynaerts, chair of the project until her retirement in March 2025, together with Marion Anker and Laurien van der Werff – who succeeded her as co-chairs – about the past five years. She asks them about the changes that have been set in motion and their hopes and plans for the future.

HK: To start off: Can you tell me about the background to this project?

Jenny Reynaerts (JR): “In 2019, the Rijksmuseum, like many art museums in the Netherlands, was approached by the arts journalist Wieteke van Zeil, who was writing an article for International Women’s Day and asked how many women artists were represented in the collection. The Rijksmuseum could not immediately answer that question, and that provided the impetus for the project. Covid delayed the launch but the project finally kicked off in 2021 with the presentation of three works by women artists in the Gallery of Honor.

Laurien van der Werff (LvdW): “The permanent presence of work by women in the Gallery of Honor is now standard policy. There are always at least three paintings by women on display there. And it’s clearly necessary: many visitors are still surprised to see that there were women artists in the seventeenth century – and very good ones at that.”

JR: “For many years, entrenched patterns of thinking led to women artists being overlooked. Once you focus on individuals and conduct research, you can tell a different story. That is actually what this project aims to do.”

HK: What do you mean — “tell a different story”?

LvdW: “Well – the story as it should be, but that has not been told in that way before because of blind spots.”

Jan Steen (1626-1679), Baker Couple Arent Oostwaard and Catharina Keizerswaard, 1658

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Marion Anker (MA): “Women are not just another story, or an addition to it, but are an integral part of the story. The project focuses on three important areas of research: women creators, women in history, and women in the history of the institution, such as women collectors and donors. Of course, it is important to include women artists in the Gallery of Honor, but there are multiple ways to pay attention to women, to tell a story that does them justice. Sometimes something simple like a change of title suffices. For example, one of Jan Steen’s paintings, originally known as Baker Arent Oostwaard and His Wife Catharina Keizerswaard, was changed to The Baker Couple Arent Oostwaard and Catharina Keizerswaard. In making this change, we are telling the story that women worked in the seventeenth century and were not just “someone’s wife.” They played an active role in society. The representation of such stories in the museum is an essential task. Our goal is to increase the permanent visibility of women in the museum, treating them on an equal footing with men.”

HK: The project has been going for five years now. What would you say is the most interesting discovery – one that has permanently changed the way you look at something?

JR: “For me, it has been the verb-oriented method, which we used a lot when rewriting object labels. It is a method developed at Uppsala University that involves describing people using verbs rather than nouns. In other words, you focus on what they do rather than who they are.”

JR: “Adopting this approach to female historical figures has yielded so many stories – there is always something interesting to relate. It has shown me that there is still much to be learned – and it has made me aware of what were my own blind spots. A key research finding is that women were far more knowledgeable and active in the arts in previous centuries than had been assumed.”

MA: “I think this research also helps to undermine the myth of the male genius. While we’re seeking out women’s stories and highlighting them, we’re also driven to ask ourselves why those stories have remained largely out of sight. I think the idea of the ‘male genius’ plays a big role here. It’s interesting to abandon the notion of a single brilliant creator of an artwork and make room for multiple perspectives.”

JR: “And not just the ‘male genius’, but the whole concept of ‘genius’. Because when a woman artist has actually risen to the fore, the narrative tends to be that she must have been a genius or she would never have succeeded. This leads to what I call the ‘victim-heroine’ discourse: every woman is described in terms of what she couldn’t do, what she wasn’t allowed to do – but despite all that, she did it anyway, and she is turned into a heroine. That’s not an accurate picture: they simply created their work.”

LvdW: “Another thing the project has taught us is that you must read all secondary sources very critically and question everything. Going back to primary sources is very important. You can often find a wealth of new information there if you interrogate them from another (female) perspective. The information is there but it has never surfaced before – because those questions were not asked.”

HK: And the Rijksmuseum also actively acquires artworks by women and objects related to women, is that right?

MA: “Yes. I should emphasize that these acquisitions are usually not fully funded from the Women of the Rijksmuseum Fund. Sometimes we cover the full amount, but with bigger acquisitions the Fund contributes, and is one of the funding streams that enables the purchase. In this way, the Fund serves as an encouragement, but the main issue remains to create more space for women in the general acquisition policy.”

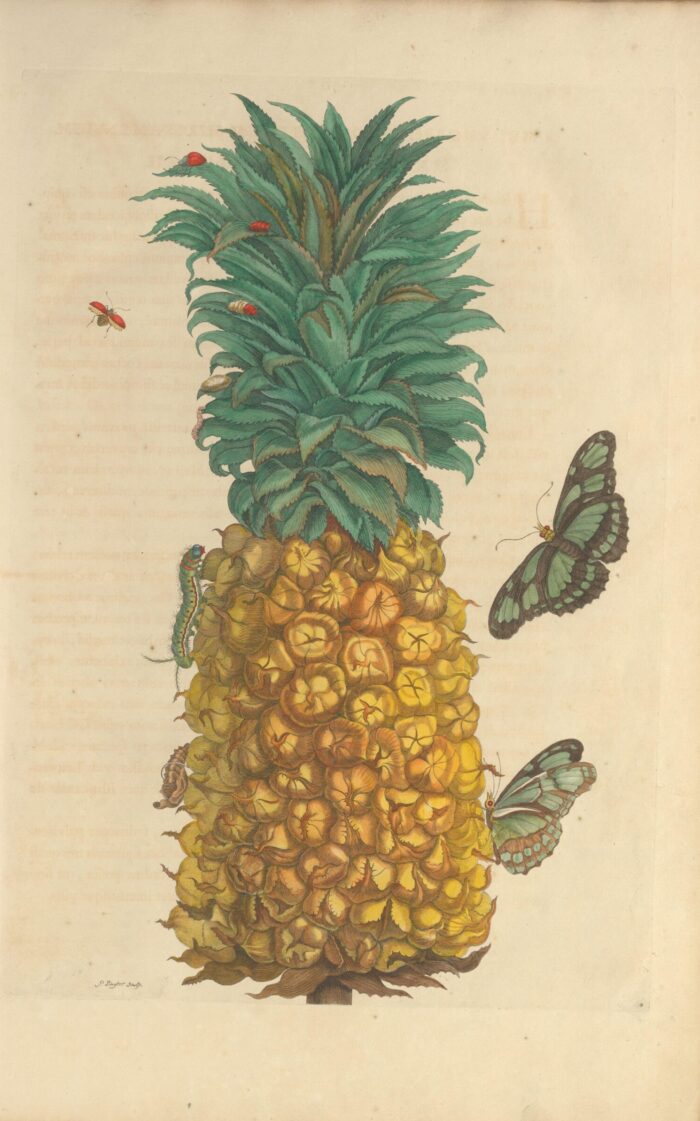

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), Pineapple with Caterpillar, Butterflies and Other Insects, 1705

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

LvdW: “Early modern highlights in acquisitions made in the past few years include work by Maria van Oosterwijck, Gesina ter Borch, and Maria Sybilla Merian. But we support acquisitions in all departments and time periods; so far over 40. For example, the Fund contributed to Jacob Ruff’s book on midwifery from 1622, an eighteenth century embroidered silk bedspread belonging to the Van Lennep family, made by Anna-Maria van Lennep-Leidstar, and a beautiful portrait by Wilhelmina Drupsteen from 1919.”

JR: “These acquisitions also demonstrate the wide range of women’s artistic output. The existing hierarchy of disciplines, with painting at the top, followed by sculpture and then the rest, is detrimental to women. They worked a lot on paper and textiles – and while these art forms were appreciated in their own time, they largely disappeared from view in the nineteenth century. That’s another revolution I’d like to see – a more equitable appreciation of different art forms. The exhibition Making Her Mark [by the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Baltimore Museum of Art, ed.] was a great step in that direction.”

HK: How will your research findings and this heightened interest ultimately be embedded in museum practice? How can you make an enduring impact?

LvdW: “I think the fact that we’re conducting this research in a museum context will ensure its lasting impact. Feminist art historians have been doing extensive research since the 1970s, so we’re certainly not the first to study women in (art) history. But the results of that research have mainly stayed within academia – they have not been translated to an enduring, clearly visible shift in approach by museums. We hope this will change now, because museums are the custodians of our collective memory.”

JR: “Exactly – and we don’t want to be just another wave of research. Our mantra is ‘permanent and self-evident’: that’s our goal.”

HK: How are the research findings being communicated to the public and to colleagues within the museum world?

JR: “The new object labels are really important for the general public. They make women in art and history into a tangible presence. We’ve rewritten over 200 labels up to now. In some cases that has just involved adding a few words, while others have meant a tremendous amount of research. The saying ‘Anonymous Was a Woman’ often turns out to be true. We frequently find that a woman was actually known, for instance as a porcelain designer, but her name is not mentioned and the work is registered as ‘anonymous’. It is very important to retrieve those names and give those women agency.”

LvdW: “For colleagues in the field there are our publications and lectures, and the annual symposium is an important event. This year the symposium is a two-day event to mark our fifth anniversary and we will focus on the present and future of gender and women’s issues in a museum context. In the next few years, we’ll be focusing on more international cooperation and expert meetings – and giving many lectures, both in the Netherlands and internationally. It’s crucial to develop partnerships with other institutions – it’s a collaborative venture. Especially now that the political climate is changing – and headwinds are picking up.”

MA: “We also believe it’s crucial to better reach a wider audience. The results of our research must be incorporated into educational materials, information in the galleries, and online. Therefore, it’s essential that staff from departments such as Education and Marketing are involved in the project. The education department is currently revising the syllabus for museum educators. Last year, we also launched the (Dutch) podcast “Women on the Wall” [Vrouwen aan de Muur, ed.] and we organize an annual public lecture. The launch last November was hosted by Katy Hessel and partly attracted a new audience.”

HK: What kinds of challenges have you faced, researching women in the art world?

JR: “I’m not sure I’d go so far as to say we encountered opposition, but there was an internal debate about the necessity for this project. Some raised objections – for instance, that the idea was too binary. For me, that was the biggest challenge. And getting enough funding, of course, to ensure we could do everything we envisaged. In fact, within five years, we have gone from lagging behind to a position in the vanguard of research – very much thanks to the financial opportunities we’ve been given [from the Women of the Rijksmuseum Fund, ed.].

MA: “Five years ago, there was a general belief that women’s emancipation was almost complete. But now there is growing awareness that much remains to be done – as the present attention to femicide shows. The world is changing – and not in ways that are more positive for women. That poses a fresh challenge for us.”

LvdW: “But we’re going full-steam ahead, and we’re conscious that we’re able to do so because we have the necessary financial resources – and we have the board of directors’ support.”

Gesina ter Borch (1631-1690), Portrait of Moses ter Borch as a Two-Year-Old, 1667 or after

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

HK: To what extent does your research include a focus on quality?

LvdW: “The issue of quality comes up repeatedly. The prevailing male benchmark excludes many women and other artists who created art in different conditions. But other kinds of quality are also worthy of consideration. If someone is able to create something that moves people – like Gesina ter Borch, for instance – that too is a mark of quality. Visitors are touched by the story behind a work.”

JR: “It is constantly claimed that ‘quality’ is determined in a very rational manner. In fact, it is based on a system of norms that was established by art historians in the nineteenth century and that everyone dutifully upholds. To break away from it, you need to be aware of mechanisms of exclusion. For instance, one of the main criteria that nineteenth-century art historians used when deciding whether to include someone in an overview was whether that artist had their own studio. That produced a historiography that is still highly influential today — which is why historiography is so important. To be honest, art history really needs to be rewritten.”

HK: The project focuses primarily on research – which is naturally the main foundation underlying everything that is displayed in the museum. But what is the role of curators in the project?

MA: “Curators are absolutely essential. There is a representative from every department and every period in the working group. Together we discuss where there is room for improvement in each of their collections. Our specific focus is embedding the female narrative, and we notice that others are doing this more and more automatically – that our colleagues are thinking about it. Both At Home in the 17th Century and the upcoming exhibition Metamorphoses are good examples in which the female perspective is treated as a self-evident part of the whole.”

“But the working group does not consist solely of curators – it’s an interdisciplinary group involving staff from all departments. Marketing, Education, Social Media, Development, Service and Security – everyone contributes their own expertise. Because of this, our approach is also informally permeating the entire organization.”

LvdW: “And that is our ultimate objective – that the working group will eventually be redundant.”

HK: This is a project – which implies that it’s a temporary, finite undertaking. Until when will it remain a separate working group? What are your plans?

MA: “The initial project plan was for five years – which we’ve completed. There’s now a new project plan for the next five years. The goal is permanent visibility and ensuring that the perspective is embedded in the organization. In four years’ time, we must evaluate how things are going. In the meantime, there are lots of exciting plans, including a book, an exhibition featuring the work of Gesina ter Borch, and international partnerships. And we’ll naturally carry on rewriting the object labels. There are plenty of activities in the pipeline.”

Jenny Reynaerts retired in March 2025 from her positions as senior curator of nineteenth-century painting and chair of the working group Women of the Rijksmuseum. Since her retirement she has focused on writing books about women and giving lectures on how to write about women – for instance in museum labels.

Laurien van der Werff is co-chair of the project Women of the Rijksmuseum. She is a cultural historian who specializes in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, works on paper and paleography.

Marion Anker is likewise co-chair of the project Women of the Rijksmuseum. She was trained as a historian and works in the museum’s History Department, focusing mainly on social-cultural history and history of the institution.

Hanna Klarenbeek is the curator of Het Loo Palace in Apeldoorn. She has been a CODART member since 2015 and a member of the program committee since 2022. She gained her doctorate in 2012 with a dissertation on the social position of women artists in the Netherlands in the nineteenth century.

Rosalie van Gulick is a project manager at CODART, and coordinates its publications and the Friends of CODART Foundation.