The Krannert Art Museum in Champaign (Illinois) acquired a flower still life by Anna Ruysch. Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Stone Table Ledge, painted by the artist round 1690, portrays twelve plants, three insects, and a snail with such precision that they can be identified by genus and species. For a detailed report on the painting and a biography of Anna Ruysch, see the text below which was written by Maureen Warren.

The painting will be on view for the first time in the exhibition Coveting Nature: Art, Collecting, and Natural History in Early Modern Europe, which runs from 31 August to 22 December 2017. To purchase the still life, Krannert Art Museum was awarded a grant from the John Needles Chester Fund, which was supplemented by the Richard M. and Rosann B. Gelvin Noel Fund.

Anna Ruysch (1666-1754), Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase on a Stone Table Ledge, ca. 1690

Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Anna Ruysch (1666-1754)

Anna Ruysch came from a preeminent Dutch family that lived in Amsterdam on the fashionable Bloemgracht (Flower Canal). Her father Frederik was a renowned professor of anatomy and botany and supervisor of the Amsterdam botanical garden.

In the 1690s, he established a museum for his remarkably life-like anatomical specimens. Anna’s mother Maria Post came from an artistic family that had ties to the House of Orange-Nassau. Her uncle Frans painted the flora and fauna of Brazil and her father Pieter was a well-known architect. Anna’s older sister Rachel became an internationally famous artist, considered by some to be one of the finest floral still life painters of all time.

At age 21, Anna married the paint dealer Isaak Hellenbroek, with whom she had at least six children. After Isaak’s death in 1749, Anna—aged 83—continued to run the family’s paint business with her son Frederik Hendrik, which was located on the Damrak: Amsterdam’s principal avenue. Along with her son, two daughters survived to adulthood: Elisabeth Susanna and Anna Geertruijd. Anna Ruysch died at age 87. In her will, she left several paintings to her children, including two of her floral still lifes for each daughter.

Anna likely studied with the Amsterdam still life painter Willem van Aelst, as her older sister Rachel did from the age of 15 or 16. Anna’s paintings greatly resemble Rachel’s in both style and subject matter. Anna, however, produced significantly fewer works because she painted as a hobby and not a profession. And Anna, like most seventeenth-century artists, rarely signed her work. But because she painted for pleasure her paintings, signed or not, are quite rare.

The painting

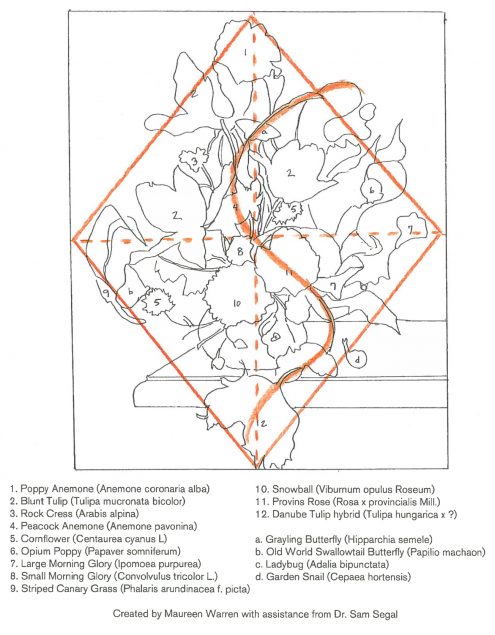

Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase depicts sixteen plant and insect species with restrained elegance. The lozenge shape of the bouquet creates an overall sense of balance.

An imaginary horizontal and vertical line structures the composition. The vertical line runs from the white poppy anemone at the top to the reddish-orange Danube tulip at the bottom. The bouquet has a low center of gravity, with the horizontal line running from the bent stalk of striped canary grass with its grey-gold seedhead at center left to the large morning glory at center right. Adding a sense of dynamism is the S-curve that runs from the opium poppy bud at upper right; along the white-highlighted stalk of canary grass in front of the grayling butterfly; across the bright red peacock anemone and provins rose at center; to the downward curving stem of the Danube tulip. (Willem van Aelst, who taught the Ruysch sisters, was the first to use S-curves to enliven his floral still lifes, a technique Rachel later exploited to great effect.) Like most seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes, light enters the composition from upper left. The majority of the flowers turn in this direction, as if drawn to the light, which contributes to the naturalism of the image and creates a visual counterbalance for the marble ledge.

Individual blossoms, grasses, and insects interject the scene with movement and vitality. Stems, leaves, and petals unfold, coil, and whither. A swallowtail butterfly alights momentarily on a bright blue cornflower.

A teensy ladybug crawls along a dewdrop-covered rose leaf. A female grayling butterfly, seen from the underside, soars between two pink and white blunt tulips. On the marble ledge, a little garden snail glides toward the translucent glass vase—perhaps on a mission to devour the roses, which already show signs of insect damage.

Still Life of Flowers in a Glass Vase looks like a real-life bouquet when in fact it is a clever fiction. It depicts flowers that bloom in different seasons and other impossibilities, such as the morning glories, which only bloom on the vine. Like her contemporaries, Ruysch consulted drawings and paintings of individual plants and insects to create her paintings. The illusion of three-dimensional space comes from her judicious use of unifying shadows and highlights and dramatic lighting effects. Chiaroscuro makes certain elements, such as the tulips and rose, appear closer to the viewer and others recede, suggesting many layers of depth within the relatively shallow space of the marble ledge.

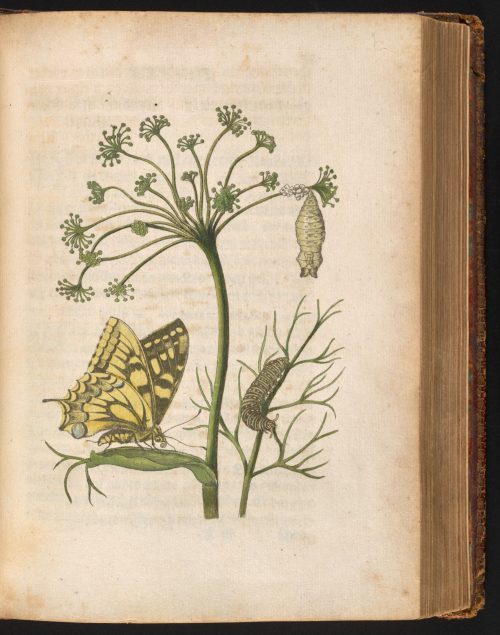

Ruysch portrays twelve plants, three insects, and a snail with such precision that they can be identified by genus and species. Her contemporaries undoubtedly appreciated this accuracy, as they would have known the scientific and monetary worth of these plants and creatures—which was significant—due to their familiarity with illustrated herbals, florilegium, and entomological studies like this one, by Maria Sibylla Merian (another of Rachel Ruysch’s teachers).

Maria Sibylla Merian, Fennel Plant with Swallowtail Caterpillar, Pupa, and Butterfly from The Caterpillars’ Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food (Nuremberg: 1679-1683)

University of Illinois, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Urbana-Champaign

Additionally, some viewers would have associated the withered tulips and insect-damaged leaves with the idea of vanitas: the inevitability of death and the necessity of living a pious life. Still others would have understood this highly accurate rendering of plants and insects as a testament to the magnificence and variety of God’s creation. Indeed, it was the multitude of meanings that floral still life paintings could convey that made them such coveted works of art.