This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 9 Summer 2017

Clothing and fashion are among the largest industries in the world, employing approximately 75 million people worldwide. In Belgium, too, fashion and textiles are important sectors. In January 2015, for example, some 33,000 men and women – of an active work force of five million – were working in the fashion and textile industries. In Belgium, moreover, household expenditure on clothing and footwear averages 4.6 percent (about the same as the amount spent on education).1 Finally, since the late 1980s, Belgian designers have been creating a furore on the international fashion scene and occupying important positions in French couture houses.2 Although at a slower pace than in France, Scandinavia and the Anglo-Saxon world, fashion has gradually come to be viewed in Belgium, too, as a relevant subject of research and object of collecting. In Belgium, the Modemuseum Hasselt (Fashion Museum Hasselt) has played a pioneering role in these developments: it seeks to boost interest in fashion both by expanding its collection and by offering a variety of attractive, compelling and low-threshold exhibitions that are solidly underpinned by research.

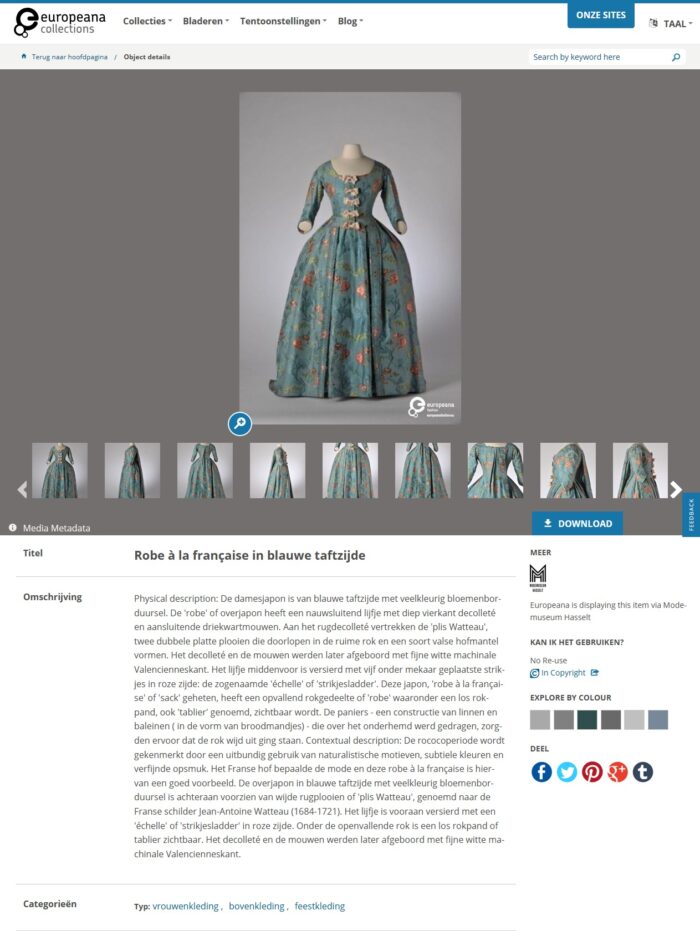

The Fashion Museum Hasselt, which is the only museum in the Low Countries devoted exclusively to clothing and fashion,3 opened its doors to the public on 8 May 1988. Its holdings, the core of which consists of the collection once owned by the Romanian scenographer and costume designer Andreï Ivaneanu (1936-1989), comprises approximately 18,000 items of clothing and accessories. Together they recount the history of Western fashion from 1750 to the present. Even though everyday apparel and anonymous garments are sometimes essential in illustrating the history of fashion (especially before 1850), our collecting policy with regard to post-1850 objects focuses on important designers that have had a great impact on the course of fashion history, such as Worth, Beer, Poiret, Lanvin, Chanel, Nina Ricci, Givenchy, Balenciaga, Dior, Cardin, Courrèges, Paco Rabanne, Valentino, Westwood, Prada, Gucci, Versace and Comme des Garçons.

Fig.1 Jean-Philippe Worth voor Maison Worth, Brocaded silk satin with turquoise & silver peacock feathers on lilac ground, ca. 1895. Modemuseum Hasselt © Modemuseum Hasselt/Kristof Vrancken

The Fashion Museum Hasselt wishes, moreover, to devote attention specifically to fashions connected with the city of Hasselt, the province of Limburg and, by extension, the Meuse-Rhine Euroregion. Concretely, this means that we collect items of clothing and accessories by Hasselt fashion stores of past and present, as well as garments worn by inhabitants of Hasselt. This local fashion story is then embedded in that of Belgian fashion production and distribution. Implicit in this approach is our policy of collecting items of apparel from large department stores such as Maison Hirsch & Co, Vaxelaire-Claes and such fashion houses as Natan and Liétart. Our regional anchoring is also visible in the sub-collection of contemporary fashion, in which creations by designers with Limburg roots and international allure, such as Martin Margiela and Raf Simons, are given special attention. Finally, the Fashion Museum Hasselt seeks to remedy the imbalance in fashion history, which is largely a story of trends in feminine clothing, by including men’s fashions as well. In contrast to what is commonly thought, the design of men’s clothing has in the past often been exceptionally creative and innovative, and this sector is certainly just as dynamic and lucrative today.

The same is true of fashions for children and young people, which are also actively collected to complete the story.

In the spring of 2018, the Fashion Museum Hasselt will devote an exhibition called Forever Young to this neglected part of fashion history. This show is an especially captivating inducement to reveal socio-cultural connotations and constructions of youth and youthfulness in the Western world.

Partly because fashion collections have only recently begun to gain attention – and the corresponding funding – they lag behind in the preservation, research and presentation of their holdings. One consequence of this is that most museums in the Low Countries that have fashion collections do not have spaces reserved for the permanent display of these collections. This is because, until very recently, fashion played a subordinate role in the museum landscape, and also because textiles and clothing place high demands on climatological and lighting conditions, which museums are not always equipped to deal with. As a result, fashion museums and collections in Belgium and the Netherlands generally make their objects accessible to the public only in temporary exhibitions and on their websites, or via aggregators such as Modemuze and the Europeana Fashion portal.4 The Fashion Museum Hasselt has opted to organize two large exhibitions a year: one of them is an exhibition with a popular theme designed to attract new target groups to the museum; the other, an exhibition, based on our own collection, that zooms in on socio-cultural, material and technical aspects of historical fashion and links them to the present-day situation.

- Fig.2 Habit à la française, 1770-1790. Modemuseum Hasselt © Modemuseum Hasselt

- Fig. 3 Green silk boy’s dress with burgundy finishes, 1870-80. Modemuseum Hasselt © Modemuseum Hasselt/Frank Gielen

Another consequence of this lag in development is the fact that all the clothing collections in the Low Countries have only one – and sometimes not even one5 – curator for the complete collection, which often encompasses objects from a wide geographical area and spanning a very long period, beginning with the seventeenth and/or eighteenth century and ending yesterday. The situation is no different at the Fashion Museum Hasselt, where I now work as curator. After more than fifteen years in academia, including seven years as an associate professor in the Department of History and Art History at Utrecht University, I switched over to the museum world in February 2015. This changeover was prompted by an awareness that dress and fashion are enormously understudied in the Low Countries and by the fact that fashion curation is still a discipline-in-the-making in which I might be able to make a difference, given my background and my love of object-based research.

A crucial element in the dissemination of knowledge about fashion is the digitization of fashion collections. Before I began to work at the Fashion Museum Hasselt, much work had already been done in the area of collection registration. A small part of our holdings had been made accessible via the museum’s own website and Erfgoedplus.6 Since 2015 we have been working on wider diffusion through the Europeana Fashion portal,7 a platform that provides online access to content from forty public and private fashion collections and now contains more than one million records, varying from historical clothing and accessories to catwalk photos, drawings and sketches, videos and fashion catalogues.

Our goal is to have 8,000 records online by the end of the year. In preparation for this, pieces from the collection are photographed and their registration is checked, corrected and, wherever necessary, supplemented. For a medium-sized museum like ours, this is an immense, time-consuming task, but well worth the effort, for the benefits are huge. Not only does it enable us to share the knowledge to be gained from our collection with as many people as possible, but it also stimulates research and facilitates lending to exhibitions. Furthermore, as the quality of the data itself is continually enhanced, our knowledge of our own collection expands accordingly.

As part of the Europeana project, for instance, we studied an ensemble of four dresses from the second half of the nineteenth century that had been donated to the museum in 1992. Genealogical research, to which the descendants made a significant contribution, enabled us to trace the original wearer of one of the dresses.

This and the other three dresses are relevant to our collection because of their historical ties to Hasselt and because they were the property of the Croonenberghs, Haumonts and Herves, families with a long tradition in the local gin distillery, textile and clothing trade, and the legal profession. These findings are part of broader research into the history of Hasselt fashions – a project in which Master’s students also take part – whose objective is to study the history of local fashions more closely, put the pieces in the collection into a clearly defined context, strengthen ties to the local community and, ideally, generate new donations.

In short, as a curator at the Fashion Museum Hasselt, I aim to continue the thorough examination of the pieces in our collection and to make the findings accessible via museum websites, digital platforms and exhibitions, vehicles that are crucial in making broad sections of the public aware of fashion and deepening their understanding of this undervalued but fascinating subject of research.

Karolien De Clippel is Curator at Fashion Museum Hasselt.

Notes

1 FashionUnited, Rijksdienst voor Sociale Zekerheid, OEC, OECD. See Fashion United, 2015 (https://fashionunited.be/statistieken-modebranche-belgie). This percentage is lower than in the Netherlands, Germany and Great Britain.

2 Raf Simons with Dior and Calvin Klein, Kris Van Assche with Dior, and Anthony Vaccarello with Saint Laurent.

3 Other museums in Belgium with relevant holdings of clothing and fashion are MoMu in Antwerp, which collects not only clothing but also flat textiles, tools and raw materials; the Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire (Royal Museums of Art and History) (KMKG) in Brussels, which have a ‘lace and costume’ collection that is administered by the Department of West European Textiles and the Museum voor het Kostuum en de Kant (Museum of Costume and Lace) in Brussels. Unlike the holdings of the Fashion Museum Hasselt, these collections always combine clothing and fashion with flat textiles and/or lace.

4 www.modemuze.nl/ ; www.europeana.eu/portal/nl/collections/fashion.

5 For example, the costume and lace collection in the KMKG has not had a specialized curator since the end of 2015. At the departure of Marguerite Goossens, long curator of this sub-collection, her position was left vacant.

6 http://www.modemuseumhasselt.be/#/collectienieuw; http://www.erfgoedplus.be/. Erfgoedplus is a heritage database that provides online access to the collections of two Belgian provinces: Limburg and Vlaams-Brabant.