This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 2 Spring 2013

The Thomson Collection of European Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto is well-known as the home of Peter Paul Rubens’ s Massacre of the Innocents, painted in 1611 and famously bought at auction in 2001 by Ken Thomson (1923-2006). Together with five Ecorchés drawings by Rubens, the Massacre reveals Thomson’s admiration of the painter’s craft. The Massacre seems an impossible achievement –the bodies of the soldiers appear to be truly three-dimensional, the grief of the mothers is painfully palpable, and the mastery of artistic traditions past is crystal clear. Perhaps less well known, but no less impossible in nature, are the 800 works of European art that preceded the Massacre of the Innocents but inspired its acquisition. Gothic ivory diptychs and freestanding sculptures of the Virgin and Child, Baroque ivory tankards and relief carvings, and British portrait miniatures amongst others all beg the question of “how were these made?!”

- Fig. 1. Prayer bead in the Form of a Skull. AGO ID 29283. The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario.

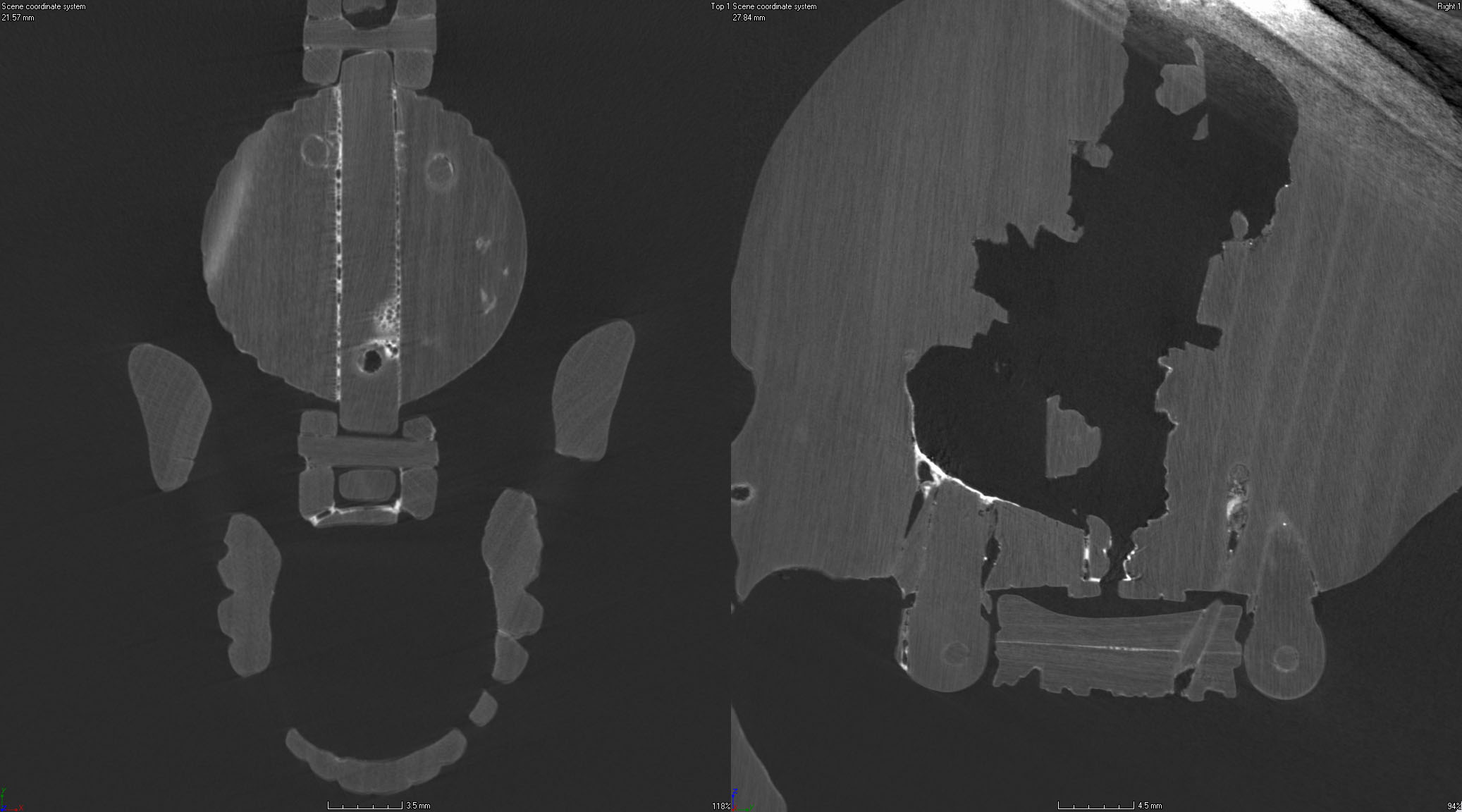

- Fig. 2. Micro CT scans of figure 1showing construction of clasp (left) and cross section of skull (right). The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario. Scans courtesy of Sustainable Archaeology at Western University.

Perhaps no group of works prompts the question more than the Thomson Collection’s ten prayer beads and two miniature devotional altarpieces, the largest collection of 16th-century devotional miniature carvings in the world. Eight of the prayer beads and the two altarpieces are Northern in origin and were possibly carved in Antwerp or another Brabantine city, while two of the beads were most likely carved in Germany. Audiences have been captivated by the 16th-century devotional boxwood carvings in the Thomson Collection since they came on view in 2008 when the Art Gallery of Ontario re-opened after the completion of architect Frank Gehry’s expansion of the Toronto arts institution. It is not uncommon to find gallery visitors gathered around the showcase that houses the carvings, expressing their amazement audibly whilst wondering aloud how they were manufactured. Recent publications by Frits Scholten, Evelin Wetter, and a group of scientists together with Rijksmuseum conservator Arie Wallert (Journal of Synchrotron Radiation, 2009, 19:310-313) provide valuable insight; however a study of the Thomson Collection devotional carvings seemed like the best course of action to satisfy our audience’s, and our own, curiosity.

- Fig. 3. Detail of figure 1 showing Christ Carrying the Cross

- Fig. 4. Detail of figure 1 showing Christ Entering Jerusalem

The basic goal of our study was to understand the intricacies of how the prayer beads and altarpieces were constructed. Given our relatively large sample size, roughly ten percent of the surviving works, we hoped that we might also identify the work of individual carvers and/or distinct workshops. We began our investigation in-house with microscopy, and quickly looked to X-radiography (Heidi Sobol, Royal Ontario Museum) for more information. A slideshow produced for the small-scale exhibition Idea Lab: Research at the AGO Investigating Miniature Ivory and Boxwood Carving displays some of these early X-radiography findings. Minute samples of adhesives, coatings and polychrome embellishment where present are being characterized at the Canadian Conservation Institute with a variety of scientific instrumentation (Elizabeth Moffatt, Canadian Conservation Institute), similarly minute textile samples are being characterized at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Richard Newman). Most recently, we turned to micro-computed tomography (Andrew Nelson, Ron Martin & Zoe Morris, Sustainable Archaeology, University of Western Ontario, London Ontario), which we feel fully satisfies our investigative needs. To date, we have micro CT-scanned two prayer beads: a skull-shaped bead that features Christ Carrying the Cross and the Crucifixion inside (AGOID. 29283) and another whose interior depicts the Last Judgement and the Coronation of the Virgin. This bead has been loosely attributed to the workshop of Adam Dirksz (AGOID.29365). The scans of these two beads revealed two distinctly different approaches to carving prayer beads: the former relatively simple, with two solid halves carved in shallow relief and hinged, and the latter unexpectedly complex.

- Fig. 5. Workshop of Adam Dirksz. Prayer bead. AGO ID.29365. The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario.

- Fig. 6. Detail of figure 5 showing The Last Judgement. AGOID.29365. The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario.

- Fig. 7. Detail of figure 5 showing the Coronation of the Virgin. The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario.

The intricately carved spherical bead has a wonderfully pierced Gothic tracery exterior and measures 6.1cm in diameter closed. When opened, interior carved hemispheres are nestled within the exterior shell where they were originally held in place with wooden pegs alone. Each interior hemisphere measures approximately 5.7 cm in diameter with a depth of approximately 3.2 cm. X-radiography and Micro-CT scanning revealed a number of clever strategies used by the sculptor to confound the viewer’s attempt to understand how the object was made. It appears that each interior hemisphere started as a solid wooden mass which was carved from the front flat plane but which contains “windows” or portions of the exterior which were removed to allow access into the deeper portions of the hemisphere from behind. The “windows” were then replaced in such a way as to be invisible to the viewer when seen from the front. There are a variety of traditional joining techniques employed in the construction of the interior hemispheres including tongue and groove joints, rabbets and butt joints secured with pegs which are held in place occasionally with what appears to be original adhesive. The precise number of carved elements used to depict the Last Judgement is not yet known. However, close to thirty separately carved, delicate spikes were set into the ceiling boss in the uppermost portion of the scene as well as set around the enthroned Christ figure. The rest of the scene appears to have been constructed out of multiple pieces carved from a single piece of boxwood and then fitted back together so that the original wood grain remained intact. The artist who made this bead had its survival in mind – by lining up the original wood grain the bead acts like a solid piece and is much less likely to sustain damage through expansion and contraction.

Fig. 8. Micro CT scan of figure 5 revealing use of pegs in depiction of Coronation of Virgin. The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario. Scans courtesy of Sustainable Archaeology at Western University.

So much of what we’ve discovered about the Thomson Collection devotional carvings raises questions around artistic intent – did the artist expect viewers to consider questions of construction? If so, did he wish to defy all attempts at visual comprehension? In any case, who is “he”? Adam Dirckz is often cited as the author of any carving with stylistic connections to a prayer bead in the Statens Museum, Copenhagen that heralds an inscription with his name. Alas, stylistic connections are not always easy to articulate as the works are so small that it is difficult to identify discernable “styles” if it was at all possible for a carver to develop his own artistic style on such a minute scale. Perhaps it is more useful to consider the individual carvings in terms of their unique characteristics.

Fig. 9. Workshop of Adam Dirksz. Prayer bead. AGOID.29365. Detail showing “Mouth of Hell.” The Thomson Collection © Art Gallery of Ontario.

Certainly, it is the unique use of polychromy in the area representing the Mouth of Hell in the Thomson bead’s Last Judgement scene that has offered us the most meaningful connection to an another important boxwood carving. In the lowest register of the upper hemisphere of the Thomson bead, the cavern-like area that represents hell includes a tiny speck of gilding on the nose of the Hell Mouth that is visible to the naked eye, as well as flickers of a colour that can be seen with the aid of a strong light source. High magnification under the microscope reveals that the cavern’s walls were coated in a bluish black pigment (the radio-opaque pigment is visible in x-rays), with red paint used selectively on the carved figures hanging upside down as well as to articulate flames in the background.

Fig. 10. Miniature tabernacle, carved in boxwood. Shown with carrying case. Registration number: WB.233 Waddesdon Bequest. The British Museum. © Trustees of the British Museum

The prayer bead that is the central part of the British Museum’s Waddesdon Bequest Miniature Tabernacle (WB.233) presents an almost identical approach to the lowest register of its lower hemisphere, which depicts the Harrowing of Hell. The Waddesdon bead’s hell scene is housed beneath a rocky outcropping remarkably similar to that of the Thomson bead’s hell scene. When examined with a strong light and at a glancing angle, the painted interior of the cavern is unmistakable in the BM bead, as in the case of the AGO bead. By extension, small details, such as the facial gestures and drapery seem to be of the same hand in the two tiny masterworks, and the identical nature of the hinges and general methods of construction used in the two beads allow us to suggest the same author with confidence.

Our research has only just begun, but will continue with the aim of organizing the Thomson prayer beads and miniature altarpieces and their counterparts into groups according to style and methods of production. We assume, at the moment, that a single workshop or artist would have approached the problem of making such an object relatively distinctly, with no desire to reinvent the construction methods that they ultimately obscured. Of course, we look forward to contradiction as much as we do to collaboration.

- Fig. 11. Miniature tabernacle, carved in boxwood. Detail of rosary bead (fig. 10).

- Fig. 12. Detail of rosary bead (figure 10). Registration number: WB.233 Waddesdon Bequest. The British Museum. © Trustees of the British Museum