This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 2 Spring 2013.

Most CODART members probably think of Tallinn, Estonia as the birthplace of the painter Michel Sittow. They might also be familiar with the collection of Netherlandish paintings and prints at the Kadriorg Art Museum. But they are less likely to know the medieval and Renaissance art of the Low Countries in Estonian collections.

The Art Museum of Estonia’s holdings of medieval and early-modern art are exhibited in the Niguliste Museum, housed in the former St. Nicholas’ Church. It is one of the most extensive and significant collections of ecclesiastical art of that period in the Baltic countries. Medieval altarpieces and wooden sculptures from northern Germany and the Low Countries form the core of the Niguliste’s collection. The Niguliste Museum is best known in northern Europe for two magnificent and monumental works by Lübeck masters of the late medieval period. The first is Danse Macabre, a painting executed in the workshop of Bernt Notke at the end of the fifteenth century; the second is the retable of the high altar of St. Nicholas’ Church, which originated in the workshop of Hermen Rode in 1478-81.

A large part of the Niguliste’s collection comprises post-Reformation ecclesiastical art from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The museum’s permanent display, which is quite small, numbers about fifty works of art. Also on exhibit are nearly one hundred tombstones dating from the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries and a collection of chandeliers from the early-modern era. The museum’s Silver Chamber houses the silver collection of the Art Museum of Estonia, founded in 1919. Its collection of ecclesiastical art was formed over the better part of a century. After the Second World War, works of religious art from other Estonian museums and churches were added to the collections formed in the 1920s and 1930s. Numerous works in the Niguliste Museum, however, come from St. Nicholas’ Church.

Netherlandish Altarpieces

The collection of the Niguliste Museum contains three Netherlandish altarpieces from the late medieval period. Two of them originated in the workshops of Bruges masters; the third is a carved altarpiece from Brussels. Only one has survived in its original form; the other two underwent alterations in the post-Reformation period. The first one, the Altarpiece of the Virgin Mary of the Brotherhood of the Black Heads, is attributed to the Bruges Master of the Saint Lucy Legend. The retable, commissioned for the altar of the Virgin Mary belonging to the Brotherhood of the Black Heads in Tallinn’s Dominican Friary, arrived in Tallinn in 1493.

Bruges Master of the Saint Lucy Legend (1430/1440-1506/1509), The Altarpiece of the Virgin Mary of the Brotherhood of the Black Heads, before 1493

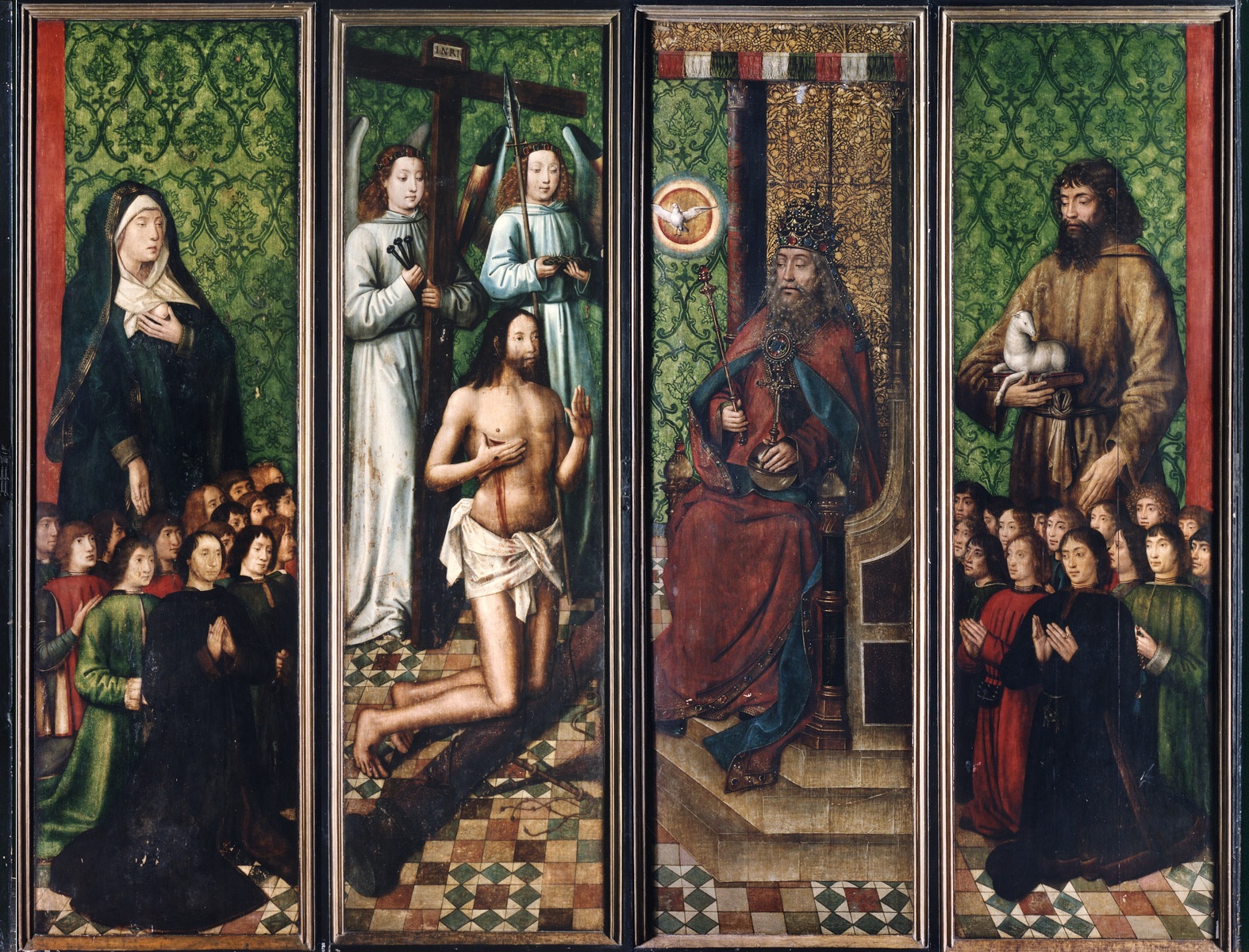

Second view of the altarpiece, Art Museum of Estonia

Bruges Master of the Saint Lucy Legend (1430/1440-1506/1509), The Altarpiece of the Virgin Mary of the Brotherhood of the Black Heads, before 1493, Art Museum of Estonia

Praying donors on the inside of the outer wings

The retable is double-winged: the first view of the altarpiece (with the wings closed) presents the Annunciation; the second view (with the outer wings open) features the Double Intercession. On the inside of the outer wings, thirty men kneel at the feet of the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist; appearing on the outside of the inner wings are God the Father and Christ with angels holding the Instruments of the Passion. The open, most celebratory view of the retable depicts the Virgin Mary enthroned, together with Saints Victor and George, the patron saints of the Brotherhood. On the inside of the inner wings, we see Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Gertrude of Nivelles. The Brotherhood of the Black Heads, which commissioned the retable, was an association of local, unmarried merchants and foreign merchants.

It had close ties to the Great Guild, an association of Tallinn’s wealthy, married merchants, from whose ranks the wardens of the altars belonging to the Brotherhood of the Black Heads were chosen. It has therefore been assumed that the two male figures in the foreground of the two groups portray members of the Great Guild.

In September 1524 there was an outbreak of iconoclasm in Tallinn. On the eve of these turbulent events, the Black Heads removed a great deal of their property from the churches and took it for safekeeping to their guildhall, where it remained until the Second World War.

The Passion Altarpiece from the workshop of the Bruges master Adriaen Isenbrandt has been dated to the first quarter of the sixteenth century and was originally installed in St. Nicholas’ Church. The altar retable has been overpainted several times, and in the sixteenth century it came to be used as an epitaph. The open retable depicts the story of Christ’s Passion.

Workshop of the Bruges master Adriaen Isenbrandt, The Passion Altarpiece, ca. 1515-20

Art Museum of Estonia

The outer wings present two pairs: the Virgin Mary with the Christ Child and the apostle James the Greater; and Saint Adrian and Saint Anthony the Great. These figures were probably painted in the first quarter of the sixteenth century. Originally the wings depicted four Franciscan saints. In the mid-sixteenth century, the altar retable was turned into the epitaph of the Lutheran superintendent of Tallinn Heinrich Bock.

His portrait – a praying figure – appears on the central panel of the retable, together with a portrait of the town’s mint master. There are also additions from later centuries: a portrait was painted into the scene depicting Christ Carrying the Cross some time in the seventeenth century. At the beginning of that century, the retable, having been turned into an epitaph, was given a top part that depicted the Resurrection.

A carved altarpiece executed in a Brussels workshop in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, as well as two wooden sculptures exhibited at the Niguliste Museum, bear witness to the spread of Southern Netherlandish carved altarpieces to the eastern side of the Baltic Sea. The carved, winged altarpiece bearing the quality mark of the Brussels woodcarvers – a tiny hammer – was made around the year 1500. Its pictorial program was originally dedicated to the Holy Kinship. Only four of the original figures have survived: Saint Anne, the Virgin Mary, and Mary Salome with her son James the Greater. The other figures date from the mid-seventeenth century. It is known that the retable, which was installed in Tallinn’s town hall, was bought in 1652 by a rural congregation for their church outside Tallinn. Modifications to the altar retable were commissioned from Tobias Heinze, a local Tallinn master.

-

Brussels workshop, The Holy Kinship Altarpiece, ca. 1500

Art Museum of Estonia

-

Brussels workshop, The Holy Kinship Altarpiece (Emerentia’s Vision on Mount Carmel), ca. 1500

Art Museum of Estonia

The members of the Holy Kinship were replaced by male figures, some of whom can be identified as apostles on the basis of their attributes. The upper wings and the inner sides of the four lower wings were overpainted. Only fragments have been preserved of the paintings on the inner sides of the lower wings, which depict episodes from the lives of Emerentia, the grandmother of the Virgin Mary, and of Mary’s mother, Anne. The first scene portrays Emerentia’s Vision on Mount Carmel, the second The Birth of Anne, the third The Marriage of Anne and Joachim, and the fourth Anne and Joachim Giving Alms to the Poor.

The collection of the Niguliste Museum also contains two wooden sculptures from the early sixteenth century that portray Roman soldiers and Longinus. The figures were most likely part of a Southern Netherlandish carved altarpiece. Though the majority of the surviving works of ecclesiastical art in the collections of Estonian museums and churches were commissioned from artists active in the artistic centers of northern Germany, the known and surviving works and also the written sources indicate that the cities had also been commissioning ecclesiastical art from the Netherlands since the second half of the fifteenth century.

-

Southern Netherlandish workshop, Two Horsemen and Longinus, early 16th century

Art Museum of Estonia

-

Southern Netherlandish workshop, Two Horsemen and Longinus, early 16th century

Art Museum of Estonia

The post-Reformation, Lutheran period saw changes in the way artwork was commissioned, with most of it now being ordered from local masters. Netherlandish art continued to exert an influence, however, as reflected, above all, in the use of such models as the prints (including examples of ornaments) by Hans Vredeman de Vries and Cornelis Floris, and the works of Peter Paul Rubens.

From St. Nicholas’ Church to the Niguliste Museum

A distinctive characteristic of the Niguliste Museum is the fact that it is housed in the former St. Nicholas’ Church. This provides the museum with a unique opportunity to present its collection of historical church art in an ecclesiastical setting. Many of the works were originally commissioned or purchased for the church and are still in situ in their historical locations.

St. Nicholas’ Church was founded in the thirteenth century and served for hundreds of years as one of Tallinn’s two parish churches. In the early 1520s, the first evangelical preachers arrived in Tallinn and St. Nicholas’ Church became Lutheran. It evolved over centuries into a church whose congregation consisted mainly of the town’s wealthy citizens and local German merchants. The glory of Hanseatic times and the affluence of the church’s congregation and donors are reflected in the ecclesiastical art commissioned for the church, both from the large artistic centers of Europe and from local workshops.

Interior of the Niguliste Museum with a seven-armed candelabrum in the foreground, Lübeck foundry, 1519

Art Museum of Estonia

The Second World War was disastrous for St. Nicholas’ Church: during the bombing of Tallinn in 1944, the church was ravaged by fire and almost all of its furnishings were destroyed. Only some of the artworks (mostly medieval) and the collection of chandeliers survived, owing to their timely evacuation. The church itself, however, was left in ruins. After the Second World War, Estonia was incorporated into the Soviet Union. In the 1950s it was suggested that the church be rebuilt, but in the Soviet era it was impossible to restore it as an ecclesiastical building. In 1953 work was started on the restoration and reconstruction of St. Nicholas’ Church as a museum of ecclesiastical art. It was thought vital to restore the ecclesiastical space as authentically as possible and to present the different stages of construction and the various chapels as magnificent examples of local ecclesiastical architecture. The restoration continued intermittently for almost thirty years. The building, a branch of the Art Museum of Estonia, opened as a museum and concert hall in 1984.

Today the Niguliste Museum is one of the most frequently visited art museums in Estonia, with nearly 101,000 visitors in 2011. In addition to the museum’s permanent and temporary exhibitions, the Niguliste’s two concert organs and excellent acoustics ensure its popularity as a concert venue.

Merike Kurisoo is curator of the Niguliste Museum in Tallinn, Estonia