This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 6 Summer 2015.

The long-awaited exhibition that will open this autumn at the British Museum is remarkable for its focus on a particular drawing technique rather than on one specific artist or period. It is the first exhibition to examine comprehensively the history of metalpoint – a technique whereby a metal stylus is used on a prepared ground – and to explore the evolution of metalpoint and its different functions in different schools.

In the technique of metalpoint, a metal stylus is used to draw on a sheet of prepared paper. Wood, as well as vellum or parchment, were mainly used as supports in the fourteenth century but were replaced by paper in the fifteenth century. The paper was prepared with a ground of bone ash (made of burnt animal bones ground into powder), mixed with a glue made of animal skin. Whereas Italian artists often used a wide variety of colors – such as pink, green and blue – most Netherlandish artists preferred pale preparations, undoubtedly to enhance the clarity of the lines.

Once a prepared sheet has dried, it is possible to draw on it with a point of gold, silver, copper or other metal. Any metal object will do, even silver coins or cutlery. The rough texture of the ground microscopically abrades the metal, so that small particles are deposited where the stylus is dragged over the surface, creating a visible mark or trace.

Metalpoint lines initially appear lighter to the draughtsman but eventually grow darker as they undergo a process that can take months or even years. The lines display a range of colors, which can be explained not only by the different metal alloys used but also by environmental conditions that can cause the metal to tarnish in different ways. Silver, the most commonly used metal, appears as brown, purple, green or sometimes even orange-brown. A gold stylus is a much more stable drawing tool, as the lines retain the same gray color they display when first applied. The fact that goldpoint is much rarer than silverpoint can be explained by the high cost of the metal.

Metalpoint is a demanding and time-consuming technique that requires the draughtsman’s painstaking attention. Unwanted lines are difficult to erase, and excessive pressure can damage the ground. It is very useful in rendering subjects in great detail, such as portrait studies or small elements – heads and hands, for example – taken from larger compositions. Metalpoint therefore became part of an artist’s training, since it required preparation and careful consideration.

The main advantages of the metalpoint technique are the meticulous precision and high degree of finish that can be achieved by using a metal stylus to produce very fine lines. Other drawing techniques available at that time – such as chalk, or pen and ink – are easier to use but do not allow for such accuracy. Graphite, which can even be sharpened and is easier to correct, did not come into use until the mid-sixteenth century.

Metalpoint also has the advantage of being a dry technique, which makes it highly suitable for use in sketchbooks, since there is no chance of mishaps, such as smudging or spilling ink. Few sketchbooks survive intact, however. Indeed, many of the surviving metalpoint sheets were most likely removed from these volumes.

Drawing in metalpoint was practiced in Europe from the late fourteenth century onward, although most surviving sheets date from the second half of the fifteenth century. These include drawings from Italian workshops run by the likes of Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael: they are either preparatory sketches or copies made by pupils or assistants. In the first two decades of the sixteenth century, German artists, such as Hans Holbein the Elder and Albrecht Dürer, seem to have preferred this exacting technique for making portrait studies and recording their travels in sketchbooks.

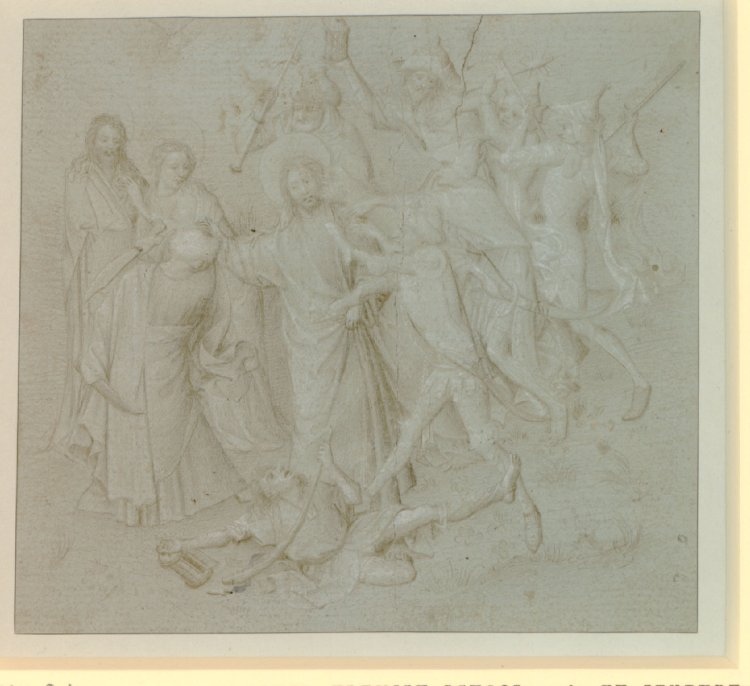

Metalpoint was used longest, however, in the Netherlands. Early metalpoint drawings on paper date from around 1400-20 and seem to be linked to manuscript illuminators working for the Burgundian court. (Fig. 1)

-

Fig. 1: Anonymous, The Arrest of Christ , silverpoint on green-prepared paper, c.1410-20

British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

-

Fig. 2: Jan van Eyck (1390-1441), Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Albergati, silverpoint on white-prepared paper, c.1432

Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

The best-known silverpoint drawing from the fifteenth century is undoubtedly the so-called Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Albergati, made by Jan van Eyck in preparation for his painting of the same subject of around 1432. (Fig. 2) Although this is a rare study for another work, most fifteenth-century metalpoint drawings can be described as workshop copies, either produced by the master himself in order to document existing artworks or made by his pupils to improve their drawing skills.

Another silverpoint sheet, datable to 1435-40, is now accepted as the only surviving drawing by Rogier van der Weyden. The stunning Head of an Unknown Woman Wearing a Veil, previously considered a portrait drawn from life, might in fact be an idealized female head, used repeatedly by Van der Weyden and his workshop. (Fig. 3) The fine cross-hatching and shading, which is almost invisible to the naked eye, lends depth and tangibility to the layers of fabric in the veil. The pearl hairpin is so realistic that it looks three-dimensional.

-

Fig. 3: Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464) (workshop), Head of an unknown Woman wearing a Veil , c.1435-40

British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

-

Fig. 4: Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464) (workshop), Head of the Virgin , c.1460-70

British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

A drawing datable to the 1460s or 1470s can also be linked to Rogier van der Weyden. (Fig. 4) Its similarity to representations of Mary in other works by Van der Weyden strongly suggests that it is a workshop drawing of the Virgin. This sheet is remarkable in that the anonymous draughtsman scratched the prepared ground to depict highlights in the hair and facial features. This technique, which has been detected only in Netherlandish drawings, seems never to have been practiced by, for instance, Italian or German artists.

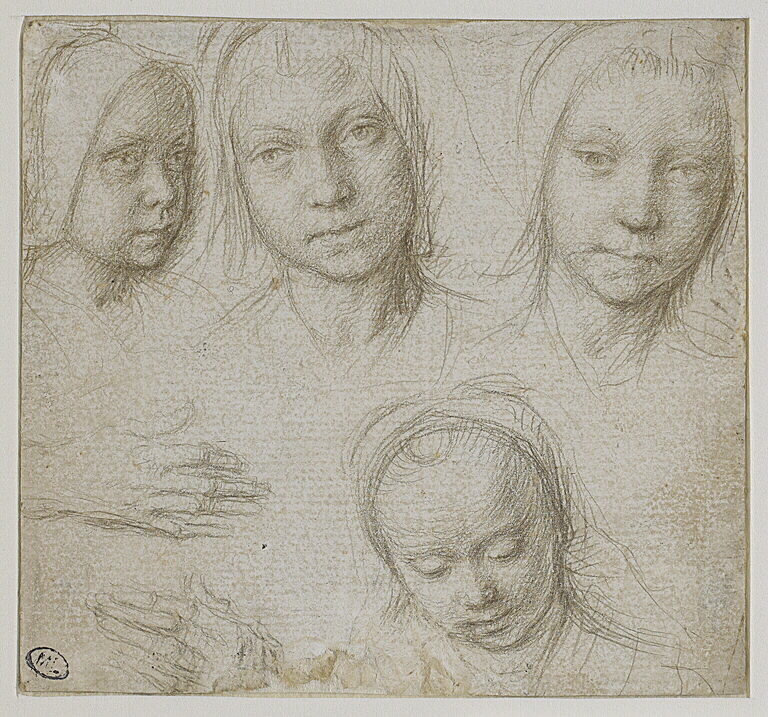

From around the beginning of the sixteenth century, Netherlandish artists such as Gerard David began to use metalpoint for more spontaneous sketches: female heads drawn from life, for example, which were probably removed from sketchbooks. (Fig. 5) By contrast, Lucas van Leyden made, around 1515, an elaborate silverpoint drawing of an allegorical scene whose meaning is still unclear. (Fig. 6)

-

Fig 5: Gerard David (1450-1523), Four Heads of Girls and Two Hands , silverpoint on white-prepared paper, c.1500-05

Musée du Louvre, Paris © Musée du Louvre

-

Fig. 6: Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), Two Nude Allegorical Figures, c.1516

British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig. 7: Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), Study of a Tobacco Plant , silverpoint on yellow-prepared vellum, c.1585

Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Metalpoint seemed to die out in the 1520s, but around 1579 it experienced a revival, particularly in the Northern Netherlands. Dutch printmakers, such as Hendrick Goltzius and Jacques de Gheyn II, produced small studies in preparation for their oval portrait prints. Goltzius was by far the most prolific user of silverpoint; almost one hundred silverpoint tafeletten (tablets) survive. He drew on sturdy sheets of vellum, which were coated with a thick ground and often a light yellow wash. These highly detailed portrait studies were minutely hatched or stippled, creating blended areas of shading. In addition to making these small portraits, Goltzius also recorded his private life in silverpoint, making portraits of himself and members of his family, a pet dog and even the plants in his garden. (Fig. 7) In a stunning, early self-portrait of around 1589, he presented himself as a successful engraver, holding a burin and a copper plate, wearing sumptuous clothing and looking confidently at the viewer.

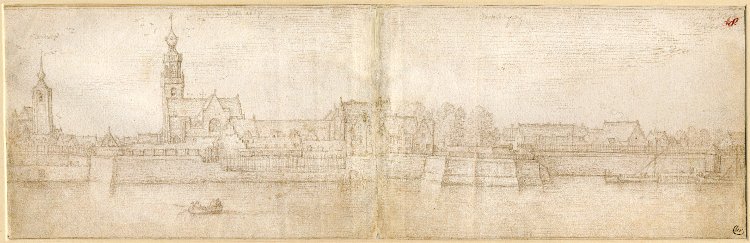

Around the same time, other artists in the Low Countries were using metalpoint to record their travels in sketchbooks. The Protestant miniature artist Hans Bol drew views of the towns and countryside he saw after being forced to flee from his native Flanders to the North in about 1584. (Fig. 8)

Fig 8: Hans Bol (1534-1593), View of Antwerp from the River Scheldt, with the Sint-Andrieskerk (St. Andrew’s Church) and the Sint-Michielsabdij (St. Michael’s Abbey) , silverpoint on two conjoined sheets of white-prepared paper, c.1583-84

British Museum, London © The Trustees of the British Museum

Fig 9: Rembrandt (1606-1669), Five Studies of Heads (recto), silverpoint on white-prepared vellum, c.1633

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Surviving seventeenth-century examples date mainly from the 1630s; they include portrait studies by printmakers and, unusually, peasant studies by Andries Both. The last major artist to use the technique in the Netherlands was Rembrandt, who briefly carried a silverpoint sketchbook on his trip to Friesland in 1633. This double-sided tafelet displays some studies of cottages and a study sheet of heads. (Fig. 9)

The technique of metalpoint subsequently died out across continental Europe but experienced a revival in nineteenth-century England in the work of William Holman Hunt and other artists who emulated Italian Old Masters. Metalpoint was still practiced sporadically in the twentieth century by such artists as Otto Dix, who used the technique to make some large portraits. A few contemporary artists – especially Americans, such as Jasper Johns and Bruce Nauman – have occasionally explored the possibilities (and limitations) of this graphic technique. The forthcoming exhibition in Washington and London will include the most interesting examples of this magnificent technique in about one hundred sheets dating from the late Middle Ages to the present. Most of these works come from the British Museum and will be complemented by major loans from other institutions in Europe and the United States.

An Van Camp is Curator of Dutch and Flemish drawings and prints at the British Museum. She has been a member of CODART since 2010.