This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 7 Winter 2015

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen (1593-1661) has been one of the forgotten figures of seventeenth-century British – and to a certain extent – Dutch portrait painting, yet the characteristics of his style make his work comparatively easy to identify.

Prolific and successful in his lifetime, his works are found in most public collections in Britain (often, it must be said, in their reserves rather than on display). There are portraits by Jonson in many private British collections, hanging on the walls of country houses, frequently in the possession of descendants of the original sitters. All his known surviving works are painted portraits (plus a handful of portrait-related drawings).

Jonson was born in London in 1593 into a Flemish/German immigrant family. Late sixteenth-century London was full of exiles from continental Europe, many of whom were Protestants escaping the re-Catholicization of the southern Netherlandish provinces. He apparently trained in the northern Netherlands, but was back in London by the beginning of 1619. His earliest known portraits are of English sitters and are dated 1619 (fig. 1). From then on Jonson painted men, women and children from the upper strata of British society – including King Charles I, whose official ‘Picture-drawer’ he became in 1632. He also made portraits of members of the Netherlandish community in London, especially those who attended the Dutch Church there, Austin Friars.

During the 1630s Jonson evidently worked extensively in Kent, too, for a network of interconnected gentry families (see fig. 2), and may possibly latterly have stayed in the house of Arnold Braems, a wealthy merchant of Flemish descent. After the outbreak of the English Civil War and the resultant collapse of court patronage, Jonson (by now aged 50) migrated with his family to the Dutch Republic in October 1643. He continued to work successfully as a portraitist there – first in the Zeeland coastal city of Middelburg, where he joined the painters’ guild, then in Amsterdam and The Hague (where there were, of course, other British exiles), and briefly returned to Middelburg before finally settling in Utrecht, where he died in prosperous circumstances in the late summer of 1661.

Fig. 2. Cornelis Jonson, Elizabeth Campion, 1631, Private Collection; photo courtesy of Christie’s Images, 2015

In terms of connoisseurship, although Jonson constantly and subtly modified his style of presentation during his long career, his portraits do tend to be moderately recognizable. Certain characteristics persist. The sitter’s head is often placed unexpectedly low in the frame (see fig. 2). The range of poses is carefully limited. The sitters are seldom presented in the act of movement, but in a modestly dignified stasis. There is a meticulous precision in the handling of jewelry, textiles and dress, and above all of the lace collars that were such signifiers of rank and wealth in early seventeenth-century Britain and the Dutch Republic (see Figs. 1 and 2). The handling of his sitters’ eyes is often particularly distinctive, with their enlarged, rounded irises and deep, curved upper lids. There may also be a gleam on the tip of the nose. In his later Dutch works there is often a light-blue or green background, although the pigments tend to have become discolored with time. As the British writer Bainbrigg Buckeridge observed in 1706: ‘He … was contemporary with Vandyck, but the greater fame of that master soon eclipsed his merits; though it must be owned his pictures had more of neat finishing, smooth Painting, and labour in drapery throughout the whole.’

Because Jonson’s handling is so quietly distinctive, identifying his work can often be straightforward. This is in contrast to other portrait painters active in London in the period 1620-1645, whose styles and identities can be extremely challenging to disentangle, and who often did not choose to sign their works. Jonson has, however, been surprisingly neglected in British, and perhaps also Dutch, art history. As a painter at the court of Charles I, he had the misfortune first to be overshadowed by the Flemish superstar Anthony van Dyck (as Buckeridge noted) and, then, after Van Dyck’s death, to find his own British career curtailed by the Civil War.

For centuries there was retrospective confusion as to whether Jonson could be called an ‘English’ or a ‘Dutch’ artist. As a result, the forms of his name used by art historians vary considerably. Jonson himself must inadvertently take some responsibility for this confusion, for at different times and in the different places where he worked he successively altered the monograms and forms of signature that he used. For instance, after he migrated to the Netherlands he signed his largest surviving work – a group portrait of the civic dignitaries of The Hague – ‘Cornelius Jonson Londini fecit, [Cornelius Jonson of London] / Anno 1647’. He subsequently signed as ‘Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen’ (of Cologne), the city from which his great-grandfather had come. So in the Netherlands Jonson seems to have emphasised his ‘foreignness’, presumably to set himself apart within a crowded market. As a result, if one looks up Johnson in the index of a Dutch publication one needs to go to the letter ‘C’ (for ‘van Ceulen’) rather than to ‘J’, as in an English-language volume.

Recent historians of British art have only rarely discussed Jonson’s work, possibly unwilling to have to tackle his Dutch period as well, while few Dutch scholars have been interested in his earlier, 24-year career in England. Indeed, it was only in 2012 that the first English works by Johnson entered a Dutch public collection, when Ruud Priem master-minded the acquisition of the paired portraits of Willem Thielen and his wife Maria de Fraeye, dated 1634, by the Catharijneconvent museum in Utrecht (figs. 3 and 4).

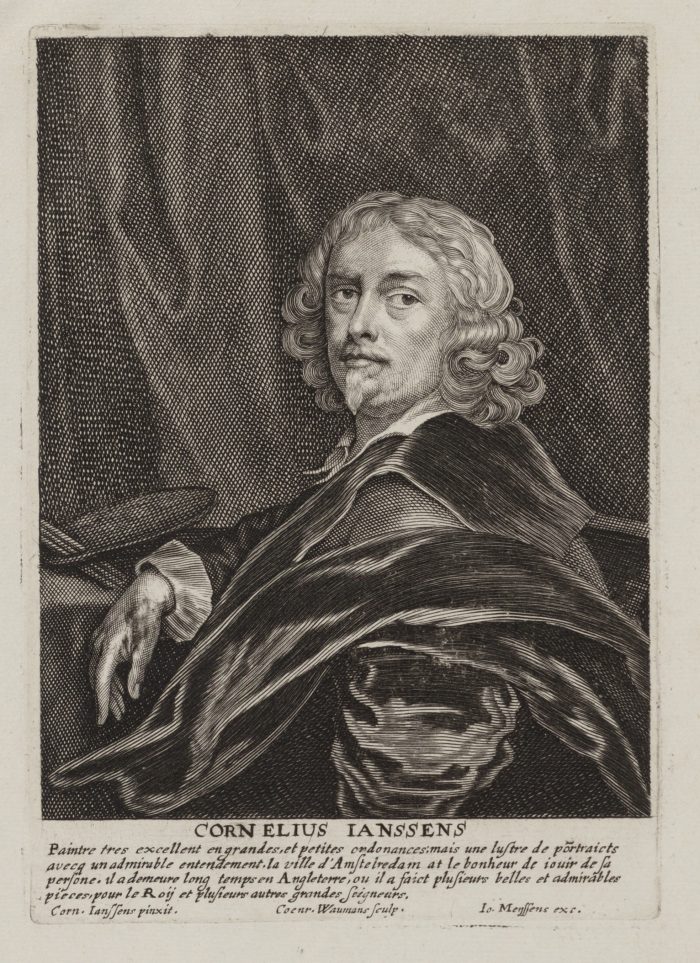

Fig. 5. Jean Meyssens and Coen Waumans after Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen, engraving, in Sebastiano Resta, The True Effigies of the Most Eminent Painters, and Other Famous Artists That Have Flourished in Europe (London, 1694), pl. 73, National Gallery of Art Library, David K. E. Bruce Fund

My own recent small exhibition on Jonson at the National Portrait Gallery in London, which ran from 15 April to 13 September 2015, was the first to focus solely on his oeuvre. The public response to the works displayed was strikingly enthusiastic. Meanwhile, the accompanying book, Cornelius Johnson, has been the first one devoted solely to Johnson’s work and career. Both projects have benefited greatly from the assistance of and information supplied by CODART members. My research into this artist, his life and his oeuvre will continue.

Jonson worked on every scale, from the tiny oval portrait miniature to the full-length and the large group image. He was the first British-born large-scale painter to sign his portraits as a matter of course, and he generally dated them as well. This makes his work of considerable interest to historians of dress, because it means developments in fashion can be traced from one year to the next by studying the details of his portraits (see fig. 2).

Cornelis Jonson’s portraits are not grand Baroque imaginative constructs. On the contrary, they have a delicacy, a dignity and, indeed, a humanity that seem to speak directly to present-day viewers.

Karen Hearn is Honorary Professor at University College London, United Kingdom. She has been an associate member of CODART since 2012.