As institutions have sought to expand the stories that they tell through their collections, they have strived to share new types of information through the incorporation of conservation- and technical investigation-based presentations in the galleries. Such installations delve into the physical histories of objects, revealing new data about artists’ materials and revisions, unearthing interventions made in in the name of preservation, and postulating new attributions based on technique and construction. Such conversations in the galleries also make public the role of science in the museum and the nature of the collaboration between curator, conservator, and conservation science.

At the heart of displaying technical information in the galleries is the notion of accessibility. How should investigative processes be explained, and with which goals in mind? What kind of visual documentation should be shared, and how should technology like iPads and QR codes be marshalled to effectively convey this information? How should scientific images be arranged vis-à-vis works of art? And is a narrative thread necessary to offer the visitor a coherent and conclusive set of “discoveries” from this work?

CODART asked three members to reflect on recent exhibitions that foregrounded technical findings. Their thoughts reveal a variety of approaches, ambitions, and achievements, and the results have set the standards for future museum presentations.

-Jacquelyn N. Coutré, CODARTfeatures editor

Presenting Technical Material in Vermeer’s Secrets

Dr. Betsy Wieseman, Curator and Head of the Department of Northern European Paintings, and Dr. Alexandra Libby, Associate Curator of Northern Baroque Paintings, National Gallery of Art in Washington

Johannes Vermeer’s quiet, enigmatic scenes of domestic interiors and serene, bust-length studies of women have inspired generations of art historians, curators, conservators and (more recently) scientists to try and understand what makes Vermeer’s art so uniquely his. For 50 years, the National Gallery of Art—home to three works by the artist, one formerly attributed to him, and two by a 20th-century forger—has worked to advance the scholarly and public understanding of Vermeer, his working process, and his technique. Although the results of material research appeared in published catalogues, neither of the National Gallery’s highly regarded exhibitions devoted to Vermeer (Johannes Vermeer [1995/1996] and Inspiration and Rivalry: Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting [2017/2018]) featured technical information within the display itself. By contrast, Vermeer’s Secrets (October 8, 2022 – January 8, 2023) (fig. 1) brought together previous material studies with new research and analysis in the first-ever installation of the Gallery’s complete collection of Vermeers—real, fake, and in between.

The project was the product of National Gallery’s prolonged closure during the COVID-19 pandemic. The unexpected gift of being able to study all our paintings in the conservation studio without the usual pressure to return them quickly to public display meant that our team of curators, conservators, research conservators and imaging scientists could conduct a deep, in-depth study of the work, the result of which was three articles in the Journal of the Historians of Netherlandish Art. Nearly two years into our project, we were given the opportunity to share these results with the public in a small focus exhibition. Translating two years of technical research into a display that was accessible for a non-specialist public within a very short turnaround time (less than 6 months) was a challenge. Our goal was twofold: we wanted to illuminate and potentially transform the understanding of how Vermeer worked and to highlight how essential close, cross-disciplinary collaboration is to the process of technical inquiry. We particularly wanted to emphasize the behind-the-scenes activities of researchers from different disciplines and the partnerships that help build a more comprehensive understanding of an artist’s creative process.

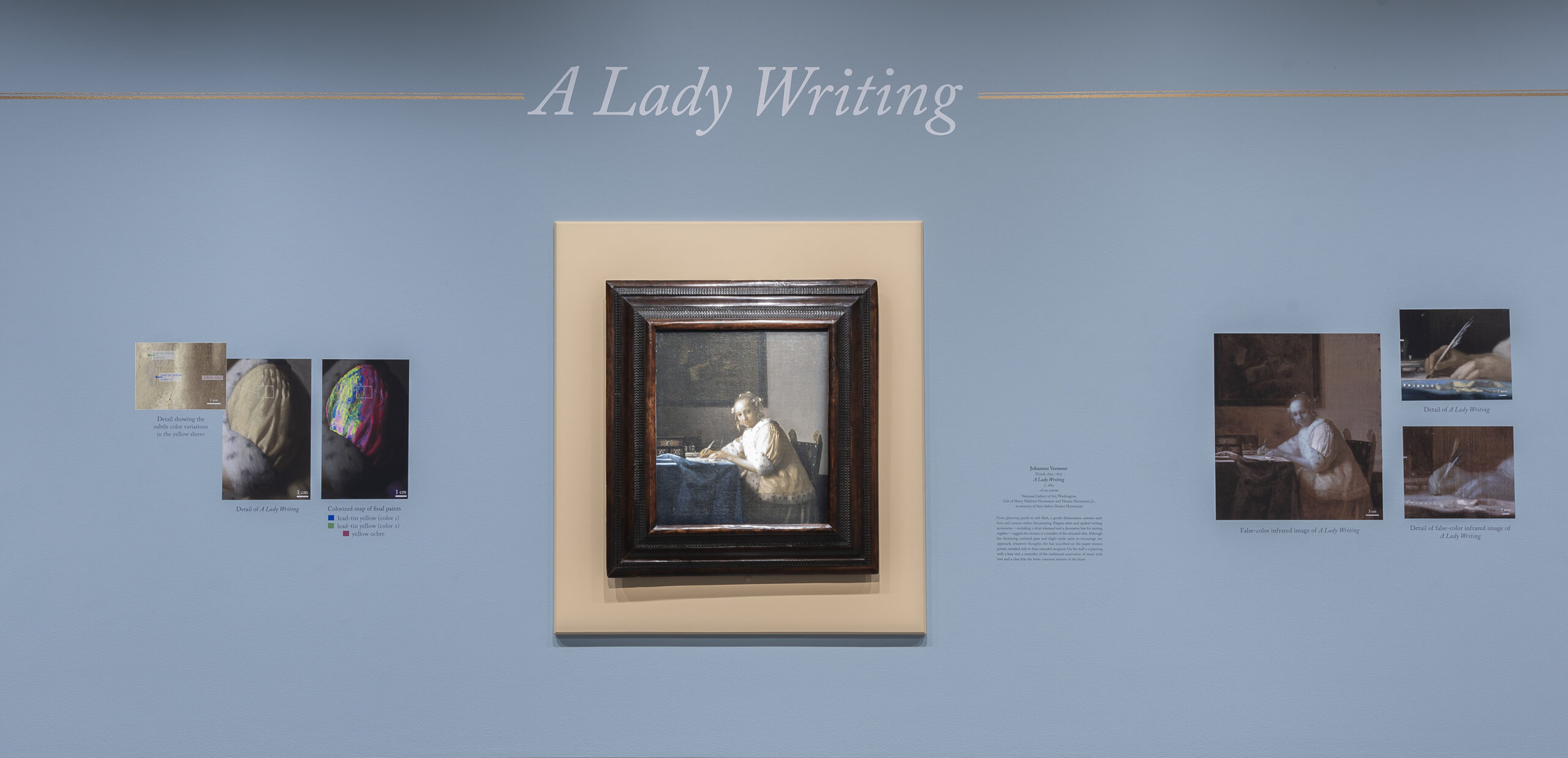

Maintaining an appropriate balance of material within the display—to not overwhelm Vermeer’s modestly-scaled paintings with massive amounts of text and technical images—meant that we had to be extremely selective in the information we presented. Mindful that most visitors have no preconceptions about how Vermeer painted, we began by directing their attention to the visible surface of his paintings, specifically his subtle and seductive approach to rendering forms suffused by light. In Lady Writing, we focused on Vermeer’s delicate modulations of light and color (for example, using three different yellow pigments in the sleeve of the woman’s garment) and virtuoso modifications to painterly technique. Photomicrographs and colorized pigment maps were displayed beside the painting to highlight how Vermeer created specific effects.

Starting with a close examination of the painting’s surface also allowed us to indicate areas of the painting where traces of underlying layers might be visible. In A Lady Writing (fig. 2), the specter of a previous compositional choice is faintly visible on the surface. Juxtaposing a false-color infrared reflectogram (IRR), which provides detailed information about different pigments below the surface, showed the change more clearly: the quill was moved from an active, upright position to lying slack in the woman’s hand, a change that shifted the focus of the narrative and enhanced its quietude.

From the surface level, we wanted to take the visitor on a journey to levels below the surface. In addition to showing compositional changes, false-color IRRs can also hint at the character of Vermeer’s underpaint, as it did for his Woman Holding a Balance (displayed nearby, fig. 3). There, we can see the preparatory stage in which he blocked out the overall distribution of color, light and shadow. It showed that on the wall behind the woman, a patch of sunlight was initially rendered as a vigorously-painted swath of lead white. Unlike the carefully blended surface paint, these strokes are short and quick, indicating a speed and boldness we don’t otherwise associate with Vermeer’s process. Here we introduced another technical imaging modality, X-ray fluorescence imaging spectroscopy (XRF), which uses X-rays to map the presence of individual chemical elements. We opted to display the XRF map for copper: copper-containing verdigris could be used a colorant, but here, it seems to have been added to black pigments to hasten their drying. Comparing data from different imaging modalities (as well as microscopic analysis of minute paint cross-sections) refined our understanding of the painting and provided further evidence that Vermeer was working more quickly in his preparatory layers than his serene surface paints might suggest.

Fig. 3. Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance (ca. 1664) in Vermeer’s Secrets

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Using the baseline knowledge about Vermeer’s painting technique borne out in the first room, the second room of the two-gallery exhibition invited visitors to think critically about the National Gallery’s two tronies—Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute—and, armed with knowledge gained from the previous room, to engage with questions of attribution and painterly technique. We presented a point-by-point comparison of the two paintings using XRF maps, photomicrographs, and dispersed pigment samples to illuminate the many compositional and material similarities. The paintings are formally quite similar; they are each painted on wood panel supports (unique for Vermeer), contain the unusual (but not atypical for Vermeer) combination of green earth in the flesh tones and vermillion in the face and lips; and include specular highlights on the inside of the women’s mouths. Alongside these similarities, we also noted differences: in the proportions and handling of the green earth and vermillion pigments; in the approach to modeling the planes and contours of the face; in the execution of the highlights; in the rendering of highlight and shadow in the folds of the women’s garments, even in the proper mixing and handling of paints. While we presented our conclusions—that Girl with a Flute was likely painted by a studio associate of Vermeer—by sharing research data and explaining our methods of study and analysis, we primarily wanted to engage our visitors in the investigative process.

This room also provided opportunity to highlight recent developments in imaging techniques employed at the National Gallery. From X-ray images, it has long been known that Girl with the Red Hat was painted directly atop a portrait of a man, rotated 180 degrees. Displaying the X-ray image beside a false-color IRR image and an XRF map of lead (present in the pigment lead white) offered a vivid demonstration of how advances in scientific imaging have completely transformed our ability to visualize the often complex stages of a painting’s genesis that are now hidden beneath the surface. We also included a case with a hyperspectral reflectance imaging system (fig. 4), so visitors could see the actual instrument used to scan paintings and produce the false-color IRR images featured throughout the exhibition.

The final component of the exhibition featured two twentieth-century Vermeer forgeries. Likely painted by Theo van Wijngarten, an associate of master forger Han van Meegeren, it seems incomprehensible today that these works were ever mistaken for authentic Vermeers. Including them in a didactic display offered an opportunity to discuss other methods of forensic technical analysis, Vermeer’s enduring popularity, and the evolution of taste.

In the end, the show was well received by visitors, staff, and the media, and we welcomed over 78,000 visitors during the 13-week run despite limiting the rooms’ capacity to 35 people at a time. But as any curator will know, there were definite challenges. Producing an exhibition in less than six months meant that many of our established processes for developing the exhibition’s “big idea,” as well as for interpretation and design, had to be strictly condensed or entirely set aside. Constraints of time and budget meant that exploring more experimental means of enhancing visitor experience—interactive displays or alternative modes of delivering interpretation—were unavailable to us, which left us with a beautiful if somewhat traditional installation (and virtually no public programs). Additionally, introducing complex imaging modalities within a highly restrictive word counts takes a great deal of patience and compromise. Our science colleagues had understandably hoped to be able to explain how tools like IRR and XRF work, but we agreed that the time spent explaining the intricacies of those techniques could not be privileged over understanding their impact. Even omitting such explanations, the installation was extremely text heavy—although the majority of visitors seemed content to spend time reading the labels and texts.

Preserving Our Heritage: Facelifts & Makeovers

Quentin Buvelot, Senior Curator, Mauritshuis, The Hague

On 7 October 2021, the Mauritshuis opened the exhibition Facelifts & Makeovers, on the theme of conservation, restoration, and technical research in the Mauritshuis over the past 25 years (fig. 5). It is hard to believe that the museum has only had an in-house conservation studio since 1995; before then, restorations were carried out at external locations, with all the risks that entailed. Since 1995, much of the collection has found its way to the studio, where the work is done by a permanent team of three conservators – an ideal situation (fig. 6). Over the years, they were increasingly able to direct their energies to complex and time-consuming restoration projects. The Mauritshuis aims not just to manage and conserve its collection to the highest possible standard, but also to ensure that the knowledge gained during restorations and research is widely shared. The public restoration in 1994 of two paintings by Johannes Vermeer – View of Delft and Girl with a Pearl Earring – was a game changer for the Mauritshuis. A temporary studio was set up in the museum, giving the public the remarkable experience of being able to watch the conservators at work. This public restoration formula has been repeated several times since then, for example with paintings by Carel Fabritius and Jan Steen, and most recently with Rogier van der Weyden’s Lamentation of Christ. In addition, the restoration of a single painting has on occasion featured in a special gallery display, as with Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp and his Saul and David, and we have also presented the latest technical research on one of our masterpieces –Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring.

That said, most restorations still take place behind the scenes in our conservation studio, which is not open to the public. Over the years, multiple new insights and discoveries were shared in our field, either in publications or at conferences, and it was time to share them with our visitors as well. I was therefore very keen to put on an exhibition. I curated the resulting show, in the marvelous design by Lies Willers (fig. 7), with my colleague, conservator Sabrina Meloni. After lengthy preliminary discussions with the other conservators, we eventually selected 20 case studies of restored paintings, from famous seventeenth-century masters like Vermeer, Rembrandt, Hals, and Potter to lesser-known artists such as Abraham Govaerts and the sixteenth-century portraitist Adriaen Key.

-

Fig. 6. The team of conservators in the Mauritshuis: left to right Abbie Vandivere, Carol Pottasch (seated) and Sabrina Meloni

Photo: Frank van der Burg

- Fig. 7. Curator of the exhibition Quentin Buvelot with Lies Willers, exhibition designer. Photo: Mike Bink

We did our best to explain the sometimes complicated stories to the public in a highly accessible way in numerous videos, animations and short podcasts. It was a real team effort: curators and conservators collaborated closely with educators and colleagues responsible for digital content. From the outset, our aim was to preserve the information on our website permanently, and we took this into account when producing the materials. The videos, animations, and short podcasts of the exhibition can still be accessed on the Mauritshuis website. A special viewing route was created for the youngest visitors, parts of which are also online.

One of the challenges we faced in preparing our stories was whittling down the large number of new insights and discoveries made over the past few years. “Kill your darlings” is easier said than done! While a book gives you the space for a comprehensive overview, complete with footnotes, an exhibition forces you to make sharp choices – while always remaining mindful of the content. We explained all the considerations involved in a restoration and what can be learned from the treatment and the accompanying research. Paintings have frequently suffered damage at some point in the past – including world-famous paintings, such as Rembrandt’s Susanna. The restoration of this painting and the examination of the panel by Petria Noble provided answers to many questions about the original size and composition of the once woodworm-infested panel (fig. 8). Thanks to this restoration and new framing, this painting has regained much of its original expressiveness.

Fig. 8. The enlarged details on the wall behind the paintings served a decorative purpose, but they also contributed to the stories that we told, like a microscope focussing on passages that would have otherwise been overlooked (such as the added section of panel in Rembrandt’s Susanna)

The exhibition also presented other important discoveries, as in the case of Vermeer’s Diana and her Nymphs, a youthful work by the painter in which the cloudy sky turned out to be a later addition. In the commentary for visitors, we told a more personal story: how, after a long process of deliberation, it was decided not to remove this cloudy sky but to conceal it, which greatly enhanced the intimacy of the image. This example again demonstrates how recent restorations can bring us closer to the artists’ original intentions – the importance of which should not be underestimated. A similar story can be told of Frans Hals’s portraits of the Olycan couple, made in 1625. The coats of arms added much later looked like stickers pasted onto the portraits, as they lacked depth. They were not removed, but hidden from view by retouching, greatly adding to the expressiveness of the two paintings. Sliding viewers on iPads near the Vermeer and Hals portraits enabled visitors to see the paintings’ condition before and after restoration – both with and without the later additions. These stories delighted visitors. However familiar they may be to curators, they are certainly not so to everyone. That is something every curator must bear in mind!

Fig. 9. The stages of producing a painting on copper, historic pigments, and (in the background) ‘work in progress’ of a painting by Pieter de Hooch, in which a fourth figure has ‘disappeared’

Facelifts and Makeovers at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, 2021

Photo: Mike Bink

To help viewers engage with the sometimes difficult choices involved in a restoration, the presentation included one that was still in progress: that of a genre painting by Pieter de Hooch, intentionally shown in stripped state – that is, with the later additions removed (fig. 9). Under the heading “Work in Progress,” we asked visitors to make a choice. The painting shows a courtyard with a man smoking a pipe, a woman drinking, and a standing girl. It was known, from an old ‘during treatment’ photograph of this painting, that the image had once included a figure seated at the table. In fact, this fourth figure, a soldier, can still be seen in an earlier version of the painting in the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. Once the yellowed varnish and later additions had been removed, the outline of the fourth figure emerged in the Mauritshuis painting. Pieter de Hooch did not paint over this soldier himself; that happened later – before 1822, in any case, long before the painting arrived at the Mauritshuis. We asked visitors to choose between three options, and the result was that most voted to reconstruct the painting based on the version in Washington. The option to leave the missing soldier ‘as-is’ was a close second place. We are still deliberating on our final decision in the restoration process, but we are certainly taking the visitors’ views into account. Our exhibition was very well received, both by the general public and fellow professionals. Like restorations themselves, this show was teamwork. Collaboration always produces better results than working alone.