This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 9 Summer 2017

The international trade in raw materials for the textile industry, the local processing of wool, silk and dyes, and the sale and export of finished textiles were vital to the economy of early-modern Antwerp. In the sixteenth century, the urge to show off newly acquired riches was so great that the authorities attempted to curb the public display of status-enhancing finery by implementing sumptuary laws, which in fact proved to have little effect. The fortunes made in the textile trade were quickly converted into ever newer fabrics and fashions. Moreover, textiles and clothing were increasingly documented in paintings and portraits, which are now fundamental sources for fashion history, because original articles of clothing are so rare. The flourishing of early-modern Southern Netherlandish painting is tightly interwoven with the developing textile industry, a symbiotic relationship of which Flemish tapestries are the most striking product. Before Rubens settled in his house and gardens on the Wapper, near the Tapissierspand (Tapestry Hall), the spot had been – appropriately enough – a bleaching field. It was on this white canvas that the artist would embark on a career without equal when he returned to Antwerp from Italy in 1608.

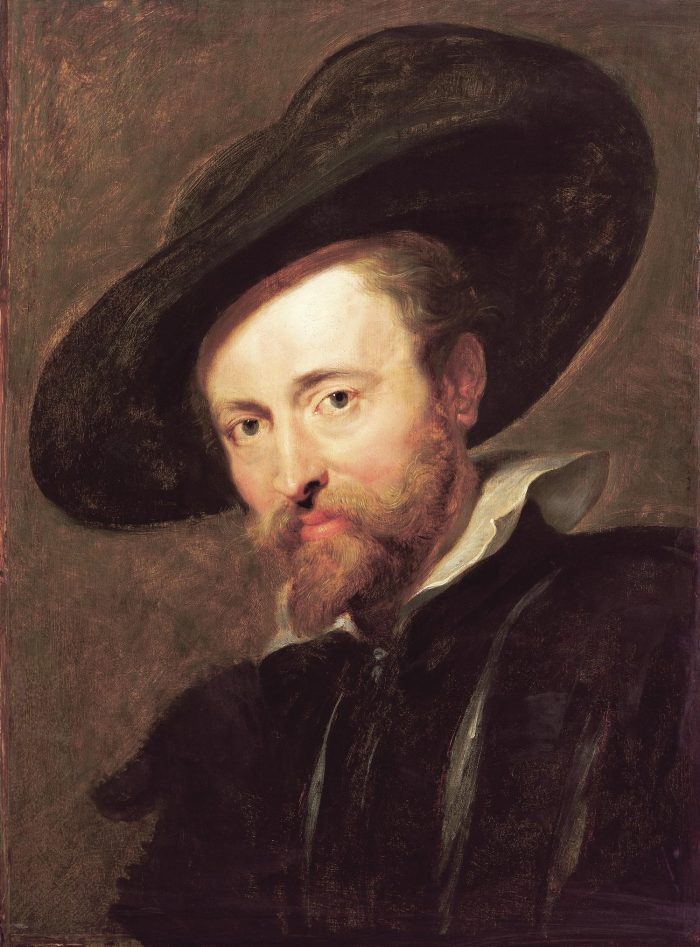

The seventeenth-century art theorist and artists’ biographer Giovanni Pietro Bellori reports in his life of Anthony van Dyck that the artist’s father was a textile dealer and his mother a talented embroiderer. She used a needle to paint landscapes and figures, thus fanning the artistic flames of her son. According to Bellori, Van Dyck was always splendidly and sumptuously attired in costly suits and courtly costumes, wearing gold chains and a plumed hat, and always going about with a retinue of servants in tow.Bellori thought that the flamboyant, high-society lifestyle of the fashionable portrait painter was the reason for his small legacy. Peter Paul Rubens, according to Bellori, chose clothing that was dignified and noble. In individual self-portraits (fig. 1), Rubens is discreetly and elegantly dressed in black, without affectation: the emphasis lies on his features, not on his clothing, which plays an important and colorful role mainly in the early Self-Portrait with his Wife, Isabella Brandt, in the Honeysuckle Bower (Munich, Alte Pinakothek). The deep purple coats in which Rubens presents himself in the portrait with Helena Fourment in New York (fig. 2) and in the Adoration of the Magi in Madrid (fig. 3) are not showy, but their color is costly and rich in meaning. After all, the Greek painter Parrhasius had also decked himself out in purple robes. Rubens’s understated wardrobe is in stark contrast to Rembrandt’s fantastical experiments, which have been the focus of studies by art and costume historians such as Marieke de Winkel.1 The portrait specialist Van Dyck, too, has already been examined in this respect by Emilie Gordenker.2

Rubens is regarded, above all, as a painter of the female nude, but Jakob Burckhardt rightly remarked: ‘Rubens has an inexhaustible variety of movement in his draped female figures, as can be seen, for instance by the most cursory glance at the gallery of the Luxembourg, and as for clothing as such, both idealized, so-called classical drapery and the elegant and opulent dress of his time, he is and remains our most important source of information. True, the great total pictorial effect to which all this is subordinated is, as a rule, of such a nature that the spectator only becomes aware gradually of these precious details. We must further note the perfect ease with which all his figures, male and female, wear their clothes, whatever they may be, for they look as if they had never worn anything else, even to the heroic battle habit somewhat casually adopted from roman monuments, and to all the glittering splendor of velvet, silk and jewelry which the eye takes in by the way as if they could not be otherwise.’3

Figs. 2 and 3 Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Self-Portrait with Helena Fourment (detail), ca. 1632-33, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, and The Adoration of the Magi (detail), 1609 and 1628-29, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Thoroughgoing study of costume was an integral part of Rubens’s activities as a painter, and a condition of the natural, could-not-be-otherwise effect that Burckhardt so rightly admires. Rubens’s so-called Costume Book in the British Museum is a repertory of Burgundian and exotic costumes that provided inspiration for figures in painted compositions.4 From his study of the classics, Rubens obtained information about the clothing of the Romans, which he then integrated into history paintings by depicting details gleaned from literary sources, such as the nails in the sandals of Roman legionaries. Details of this kind were certainly noted and admired by an intellectual public who relished his antiquarian references. Rubens, his brother Filip, a historian, and his son Albert shared a scholarly interest in costume history. A study by Albert, De re vestiaria veterum, published posthumously in 1665, unraveled the meaning of various types of Roman togas.

Meanwhile, the Antwerp archives contain threads of interest that can provide us with information on the personal wardrobes of Rubens and his contemporaries. From the settlement of Rubens’s estate, documented in the Staetmasse of 20 November 1645 and preserved in the Antwerp Felixarchief (fig. 4), it appears that the artist’s clothing was sold after his death on 30 May 1640 for 1,093 guilders.5 As mourning clothes, his widow bought gloves and fans, two pairs of mourning shoes, stockings for herself and the children, and a mourning huik (a mantle to cover the head, which could be worn as a veil). Mourning collars and cuffs of linen were purchased for the children, and the household staff also wore mourning clothes bought at the heirs’ expense. The bier, the house and the choir of the St.-Jacobskerk were hung with fabrics purchased from Peeter Vermeulen and David De Schot, dealers in wool and silk. According to the Staetmasse, Vermeulen and particularly De Schot, a seller of silk cloth, supplied large amounts of fabric to the Rubens household even before his death. The same document mentions current accounts with the linen dealer Adriaen van Leemput, the hat seller Jan Municx (who also served the ladies of the Moretus family), the shoemaker Hans Hermans, the tailors Bertram del Baren and Christoffel Notarp, various washerwomen, an anonymous furrier, and finally, the silk seller Cornelis van Wyck.

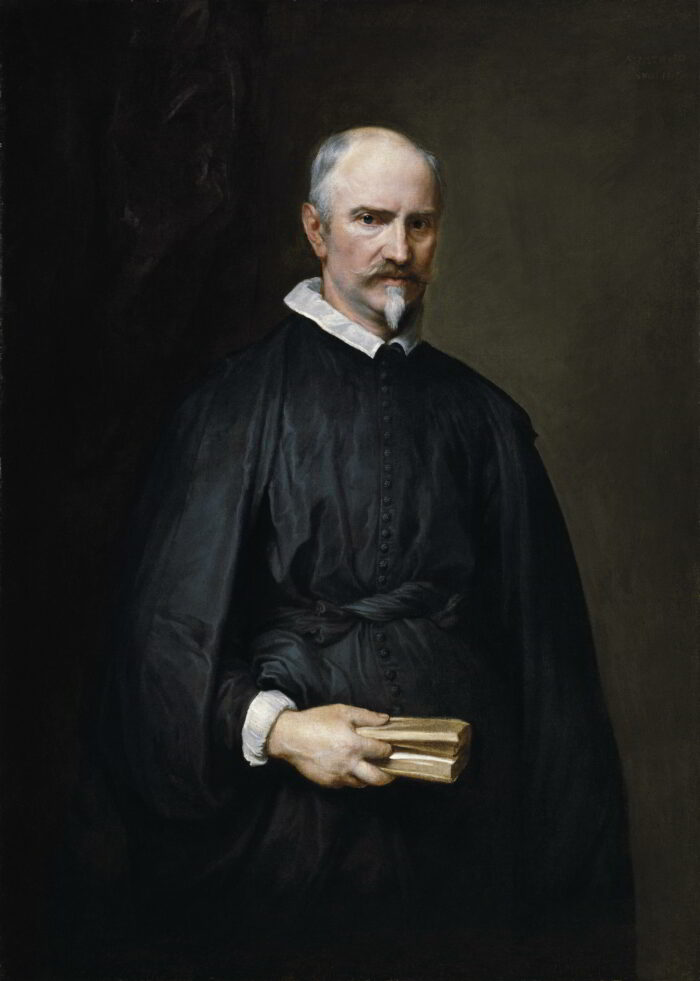

Fig. 5. Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Portrait of Antonio de Tassis, ca. 1634

Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein (The Princely Collections), Vaduz-Vienna

Fig. 6. Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Portrait of Marie de Tassis, ca. 1634

Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein (The Princely Collections), Vaduz-Vienna

Seven Grootboecken (account books) kept by Cornelis van Wyck, which record the sale of lace, ribbon, buttons and other silk accessories to the Antwerp elite for the period 1600-46, are preserved in the Plantinian archives.6 Van Wyck, who managed his business well, was buried in 1661 in a chapel built at his expense in the choir of the Victorine convent.7 In 1629 he served as burgomaster of the city, and from December 1638 as almoner. The holder of this prominent position was required to spend a great deal of money from his own pocket, and in this capacity Van Wyck clothed foundlings, lunatics and the poor. He kept precise records of expenditure for large amounts of bread, linen, woolen cloth, shoes and woolen blankets.8 Contrasting with the painstaking documentation of these necessities are the Grootboecken, which paint an equally detailed picture of the luxury business that made Van Wyck’s generosity possible. With such names as Christyn, Tucher, Godines, Van der Goes, Reyniers, Happaert, Valckenisse, Ximenez, Della Faille, Brant, Tassis, Respaigne, and Vinck among his clientele, Van Wyck supplied his wares on credit to the most notable families of Antwerp. Rubens and Jan Brueghel were among his regular customers, and other of his clients are known from their portraits, painted by Rubens, Cornelis de Vos and Anthony van Dyck.

Antonio de Tassis (fig. 5), for example, appears in Van Wyck’s account books between 1630 and 1634 as a buyer of silk ribbon, galloon, satin, lace, braided cords, and buttons intended for his daughter Marie. The portrait that Van Dyck painted of her in this period (fig. 6) probably displays ribbon from Van Wyck’s colorful shop, where passementerie (trimmings of gold or silver lace) was sold by the ell and decorative buttons by the dozen. Only a few years later, Marie died of complications after giving birth to twins. An inventory drawn up in July 1638, after her death, allows us to join her widower, a notary and her father in sifting through her possessions.9 In one drawer we find an old piece of gold braid, in another two fans. It is possible that the contents of the drawers reminded the new grandfather of carefree times in Van Wyck’s shop, and the fans made him think of his daughter’s pose in Van Dyck’s portrait of her.

Fig. 7. Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Portrait of Nicolaas de Respaigne, ca. 1620

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel

Fig. 8. Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Portrait of Albert and Nicolaas Rubens, ca. 1626

Sammlungen des Fürsten von und zu Liechtenstein (The Princely Collections), Vaduz-Vienna

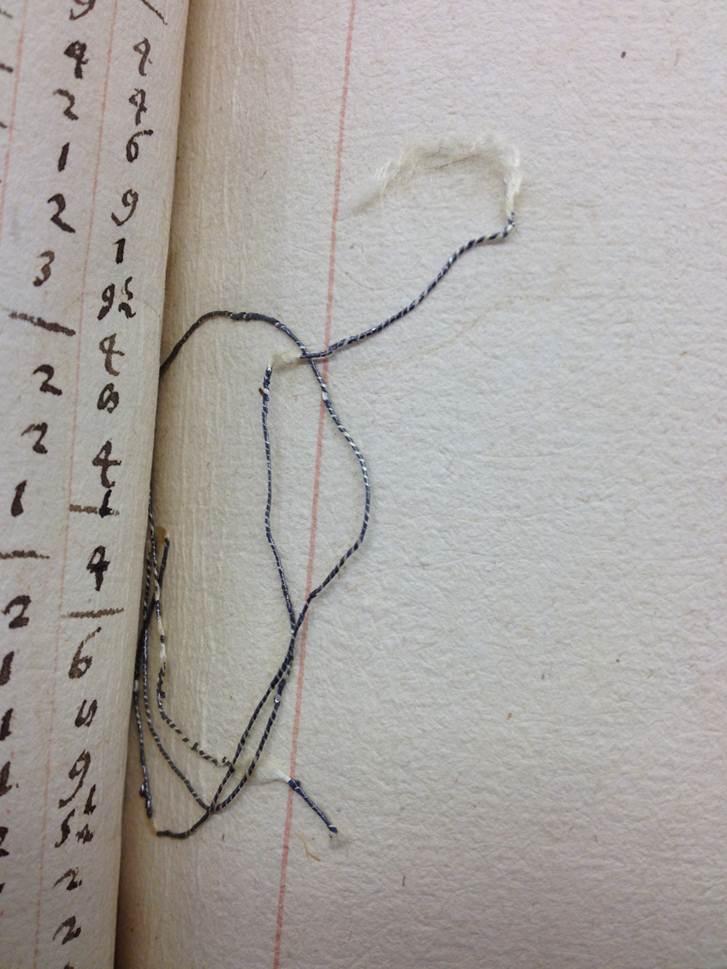

Many details from Rubens’s own account of his dealings with Van Wyck – which include bills for ells and ells of ribbon in hues of mother-of-pearl, golden yellow, incarnadine, dove gray, light blue and violet – call to mind the French-inspired clothing that Helena Fourment wore when Rubens portrayed her. A succession of purchases made in the course of the preparations for Rubens’s marriage to Helena Fourment on 6 December 1630 can be followed in detail. The ‘wide yellow shoe ribbon’ (‘gheel breet schoenlint’) bought earlier by Rubens recalls the bow on Nicolaas Rubens’s shoe in the portrait in Liechtenstein (fig. 7). The money spent on Van Wyck’s wares by Nicolaas de Respaigne (fig. 8), who is exotically attired in his portrait, do not differ from the sums expended by his fellow townsmen. Where loose ends of silk thread remain stuck between the pages of Van Wyck’s ledgers, the handwriting flows almost seamlessly into the materiality of his merchandise (fig. 9). Such archival discoveries are, in essence, insignificant – no more than footnotes to the larger narratives of art history. Even so, Van Wyck’s bulky ledgers serve to weave Rubens and his family into the social fabric of Antwerp and evoke a whole procession of well-known sitters.

This autumn Brepols will publish the proceedings of the conference (Un)dressing Rubens: Fashion and Painting in Seventeenth-Century Antwerp, which took place on 8 and 9 May 2014 at the Rubenianum and was co-organized by the University of Leuven. This publication, edited by Lieneke Nijkamp and Abigail Newman, contains contributions by Bianca du Mortier, Karen Hearn, Pilar Benito, Hannelore Magnus, Susan Miller, Johannes Pietsch, Frieda Sorber, Isis Sturtewagen, Sara van Dijk, Susan Vincent, Bert Watteeuw and Philipp Zitzlsperger. From the perspective of their own disciplines, the authors elucidate Rubens’s use of textiles and clothing as bearers of meaning in individual paintings, and examine in detail both the wardrobes of Rubens’s contemporaries and characteristic elements of the seventeenth-century silhouette. The various approaches to the subject are based on iconographic, textile-historical, archaeological, archival and literary source material.

Bert Watteeuw is Curator of Research Collections at the Rubenianum in Antwerp. He has been a member of CODART since 2011.

Notes

1 Marieke de Winkel, Fashion and Fancy: Dress and Meaning in Rembrandt’s Paintings, Amsterdam University Press, 2006.

2 Emilie Gordenker, Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) and the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture, Pictura Nova VIII, Turnhout 2001.

3 Jacob Burckhardt, Erinnerungen aus Rubens, Basel 1898, p. 80 (English translation taken from Recollections of Rubens, London 1950, pp. 39-40).

4 See Kristin Lohse Belkin, The Costume Book, Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard 24, Brussels 1978.

5 Antwerp, Felixarchief, N 1894. Transcribed in full in Pierre Génard, ‘De Nalatenschap van P. P. Rubens’, in Antwerpsch Archievenblad 2, Antwerp 1865, pp. 69-163, esp. p. 72.

6 Antwerp, Museum Plantin-Moretus. Plantinian Archives 1251, 1253, 1255, 1257, 1266, 1273, 1285.

7 Verzameling der graf- en gedenkschriften van de provincie Antwerpen (Collection of epitaphs and obituaries of the province of Antwerp), Antwerp 1856-1903, vol. 4, p. 398.

8 Cornelis van Wyck, Boek gehouden als bouwmeester en aalmoezenier (Accounts kept as architect and almoner), Antwerp, Museum Plantin-Moretus, Plantinian Archives 1193, fols. 33-91.

9 Erik Duverger, Antwerpse kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw, Brussels 1984-2009, vol. 4, p. 166.