This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 5 Winter 2014.

Two articles in the previous issue of the eZine had to do with drawings, but the editorial board has decided to spotlight this art by devoting an entire issue to drawings. Despite their huge diversity and the existence of splendid collections, these works of art are too often neglected by the art-loving public. Drawings are, after all, relatively sober in character and small in size, so it stands to reason that the average viewer is more easily seduced by the color and expressive splendor of paintings. In fact, the exciting aspect of drawings is often overlooked, namely that they afford the viewer a close-up glimpse of the creative process of the artist. The scant interest in drawings can also be attributed to their inconspicuous existence, since the fragility of works on paper means that they are usually kept in boxes, and displayed – if at all – only for short periods and in dimmed light.

Karel van Mander, who understood better than anyone the importance of drawing, wrote in 1604 in his Grondt der Edel Vrij Schilder-const (Foundation of the Noble Liberal Art of Painting) that the art of drawing is “the father of painting.” In one of the most important seventeenth-century texts on drawing, Inleydinge tot de Al-ghemeene Teycken-Konst (Introduction to the General Art of Drawing) of 1668, Willem Goeree wrote that every artist must master the art of drawing and that a pupil’s training must begin with drawing.

Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464) (workshop), Head of an unknown Woman wearing a Veil, c.1435-40

British Museum, London

Yet in his opinion, drawing must not be limited to pupils; his advice to all masters was to continue drawing throughout their careers.

Little is known about how the art of drawing was viewed in the sixteenth century, let alone the fifteenth. Very few fifteenth-century Netherlandish drawings survive; there are only about seven hundred sheets worldwide. Artists did indeed engage in drawing, but this usually involved making copies after paintings, either as part of the learning process or as working material, such as drawings made preparatory to another artwork. Presumably, however, most of the preliminary drawings made at the time of Rogier van der Weyden were applied directly to the panel, which largely explains the small number of drawings that survive from this period. Many more drawings are known from the sixteenth century, by which time the function of drawing was changing, and more emphasis came to be placed on the artist’s own invention and his observation of the world around him. At the end of the sixteenth century, the art of drawing was developing rapidly: artists ventured to experiment with different techniques and had begun to draw from life. Some drawings, which took on the status of independent works of art, were even signed.

Drawings by many famous sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Flemish and Northern Netherlandish painters have been preserved. Peter Paul Rubens, for example, produced a great many drawings, which he considered unique working material that should not fall into the hands of other artists and perhaps be copied. He even stipulated this in his will. Rembrandt, too, was a gifted draughtsman, to whom some one thousand drawings are attributed, although the authenticity of some has been questioned.

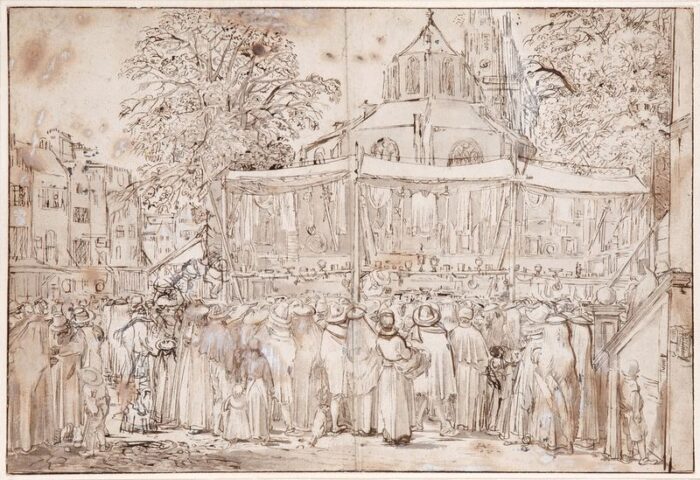

Willem Pietersz Buytewech (1591-1624), Lottery in The Hague, ca. 1617-22

Fondation Custodia, coll. Frits Lugt, Paris

It is interesting to note that a few great artists – Frans Hals, Pieter de Hooch and Johannes Vermeer – left no drawings that can be assigned to them with certainty. A number of masters who are less well known to the general public, such as Willem van de Velde the Elder, were not only painters but also inspired draughtsmen, and there are, oddly enough, artists who had no notable reputation as painters but excelled as draughtsmen, such as Willem Pietersz Buytewech.

This eZine discusses not only well-known collections of Flemish and Northern Netherlandish drawings, but also collections in small, lesser-known museums and in private hands. In addition, Clara de la Peña McTigue examines a large-scale restoration project, providing the upbeat to the theme of the next issue, which will be devoted to technical art history.

Geerte Broersma, Project Associate CODART

Karel van Mander (1548-1606), Drunken Soldier Accompanied by a Woman, 1588

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam