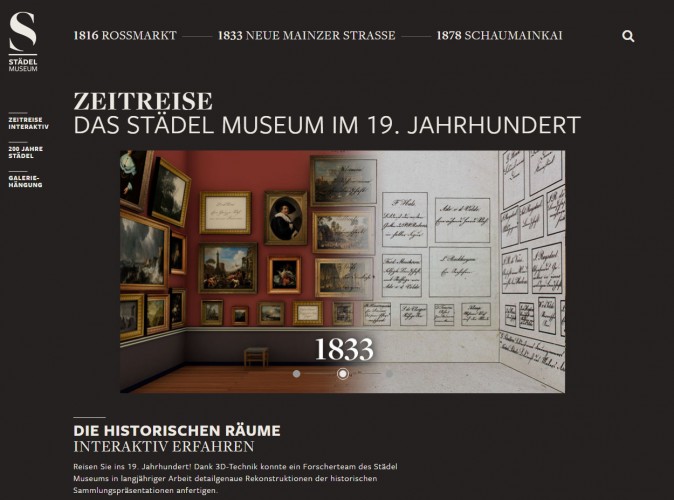

Last week, the Städel Museum launched their online research project Time Machine. Visitors can now explore the historical exhibition rooms and hangings from the beginnings of the Städel Museum in three-dimensional constructions on the museum’s website (zeitreise.staedelmuseum.de).

The website of the project offers accurate and detailed 3D reconstructions of the presentation of the Städel’s collection at its three locations. It also includes in-depth information on the provenance of all paintings belonging to the collection at the respective points in time, details on the history of sales and losses, relevant inventory entries, and texts from selected nineteenth-century catalogues.

Dr. Almut Pollmer-Schmidt, Associate Curator of Dutch, Flemish and German Painting, assisted in the project. She wrote about her work for the Time Machine and in our Curator in the spotlight of June 2016.

Information from the press release, 29 September 2016

As of today, the historical locations of the Städel Museum in the years 1816, 1833, and 1878, the respective presentations of the collection, and the works on display then can be viewed and relived online. The results of long-term research and reconstruction work on the history of collecting at the Städel Museum and the different forms of its holdings’ presentation in the nineteenth century are now freely accessible at zeitreise.staedelmuseum.de. Another way of experiencing the research results virtually live is to download the app developed especially for the mobile virtual reality headset “Samsung Gear VR” from the Oculus Store.

The website of the research project realised under Jochen Sander, Head of German, Dutch and Flemish Paintings before 1800, offers accurate and detailed 3D reconstructions of the presentation of the Städel’s collection at its three locations. Both the museum founder Johann Friedrich Städel’s private house on Rossmarkt of 1816 and the palace on Neue Mainzer Strasse, the first actual museum building accommodating the collection from 1833 on, were elaborately reconstructed. The new building on Schaumainkai, which opened its doors in 1878 and has been home to the museum to this day, and its original presentation are also part of the journey through time. The website includes in-depth information on the provenance of all paintings belonging to the collection at the respective points in time, details on the history of sales and losses, relevant inventory entries, and texts from selected nineteenth-century catalogues. Entries from scholarly catalogues presenting the collection’s holdings shed light on the current state of research. The website also offers a virtual tour through the interior of the rooms on Schaumainkai as they presented themselves in 1878. One may take this tour by using either a programme for personal computers or an app for the virtual reality headset “Samsung Gear VR,” which provide completely new insights.

This ground-breaking project shows how the most recent technological developments may be used for the generation and presentation of art-historical research results concerning an institution’s history of collecting and exhibiting its holdings in an appealing and beneficial manner. This contemporary and freely accessible presentation of research addresses both experts and interested lay people.

“The analysis of historical collection contexts has become a central scholarly issue. Revealing, not least, how tied to a particular period our perception of artworks is, the digital visualisation of how the Städel Museum presented its holdings in the nineteenth century is the first reconstruction of its kind that concerns an important civic collection,” Dr. Jochen Sander, deputy Director of the Städel, Head of German, Dutch and Flemish Paintings before 1800, and head of the research project, points out.

The VR implementation of the project “Time Machine. The Städel Museum in the Nineteenth Century” has been made possible by Samsung Electronics, Corporate Partner of the Städel Museum. The research project could be realised with additional support from the Foundation Polytechnische Gesellschaft Frankfurt am Main.

Thanks to the intense research work undertaken by the Städel, visitors can explore the various historical exhibition rooms und hangings from the beginnings of the Städel Museum in digital three-dimensional constructions on the website. This allows to compare the institution’s changing forms of presentation and to have a closer look at its manifold transformations. The project started as early as in the 1990s with the transcription of the historical inventory books in the museum’s old masters department; these inventories were used for preparing the scholarly catalogues of the collection’s holdings and the reconstruction of the paintings’ provenance. Following the international standards in the field, the information was systematised and entered into a database in 2011/12. Historical documents provided details for the visualisation of the works’ exact presentations: mounting plans, inventory books, gallery guides, and catalogues convey a good impression of how the collection was presented in 1816, 1833, and 1878. Important sources have been digitised and are accessible on the website. Four views of rooms in the museum on the Neue Mainzer Strasse painted by the British artist Mary Ellen Best (1809–1891) in 1835 as well as the photographs of the interior of the building on Schaumainkai in the archives of the Städel Museum proved to be particularly useful for the reconstruction. The results of the art historian Corina Meyer’s study Die Geburt des bürgerlichen Kunstmuseums – Johann Friedrich Städel und sein Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt am Main published in 2013 were also taken into consideration.

The state of research on Baroque hanging

The art-historical interest in past contexts of collecting and presenting works of art has increased considerably in recent years. The historical presentations of the painting galleries in Dresden, Kassel, Vienna, Paris, and Düsseldorf, all of which are based on eighteenth-century princely collections, have thus been analysed, for instance. The reconstruction of the presentations of the Städel’s collection in the nineteenth century now provides the first example of an important civic collection; the Städel Museum, which celebrated its bicentennial in 2015, is the oldest German museum foundation of this kind. Unlike the aristocratic collections of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries motivated by prestige purposes, the civic Städel, informed by the ideals of Enlightenment, saw itself as an educational institution committed to the city’s society from its very beginnings. Art-historical significance instead of ceremonial self-presentation determined the selection of works and their presentation. These new ideals became manifest in the arrangement of the art works in the museum’s rooms of which the complex visualisation of the layout of the rooms and the hanging of the works now conveys a perfect impression for the first time by means of 3D reconstructions.

As the reconstructions reveal in a visually impressive manner, the symmetrical hanging made the walls art works in themselves: the pictures were arranged close to each other on coloured walls in line with the imaginary central axis of the room in vertical columns and horizontal registers. Pendants hung in mirror-inverted positions could be directly related to each other visually. This sumptuous, even, apparently harmonious presentation of paintings, which immediately invited the visitor to comparisons, would be regarded as the ideal solution in terms of presentation and education not only at the Städel until about 1900. It was only in the early twentieth century that the form of hanging common today came to prevail: the new approach was concerned with seeing the individual work exert its auratic effect by itself. This development, which has already been outstripped by the museum and exhibition practice in the meantime, culminated in the presentation ideal of the white cube. This is why “Time Machine” not least elucidates how tied to a particular period our patterns of viewing works of art are.