This article is derived from a lecture given at the CODART Symposium “The World of Dutch and Flemish Art,” 15 October 2013, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

On 13 April 2013 the Rijksmuseum opened its doors to the public again after renovations that lasted almost ten years. For many, and certainly for the members of CODART, this occasion signaled a happy reunion with countless old friends. Paintings by Van der Helst, Steen, Vermeer and of course Rembrandt can once more be seen in the galleries.

The reopening of the museum also brought about significant changes in the installation. The fine arts, decorative arts and historical artefacts are no longer shown in different departments, but are integrated in a way that is unprecedented in the Rijksmuseum. Many visitors, therefore, will not only find old friends but will make some new ones too by discovering the silversmith Adam van Vianen, the furniture-maker Herman Doomer and the Delftware-producer Lambertus van Eenhoorn.

The collections of the Rijksmuseum have histories that are long and sometimes very complicated. Most CODART members are probably more familiar with the history of the painting collection, so I will introduce some of the collectors and donors that have helped form the collections of Dutch decorative arts. Through them, I will offer some insights into the evolving presentation history of the decorative arts in the museum.

From Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden to Nederlandsch Museum

The core of the Rijksmuseum’s collection of decorative arts is formed by the Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden (Royal Cabinet of Curiosities), which opened its doors to the public in 1816. The Koninklijk Kabinet combined the remainder of the collections of the former stadholders with the collection of Chinese art assembled by the Hague lawyer Jean Theodore Royer and bequeathed to King Willem I by his widow. The Koninklijk Kabinet was founded in The Hague, even though the Rijksmuseum of Paintings, which included a number of historical artefacts, had already been moved to the Trippenhuis in Amsterdam. The Koninklijk Kabinet was initially located on the Buitenhof, but in 1822 it was moved to the ground floor of the Mauritshuis, the upper floor of which housed the Royal Cabinet of Paintings.

Jean Toutin (1578-1644) and Antoine Mazurier, Watch with enameled case, commemorating the marriage of William II and Mary Stuart, 1641

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

This pocket watch is a splendid example of the kind of object that came to the Koninklijk Kabinet via the collections of the former stadholders. It was made to mark the marriage of Stadholder Willem II and Mary Stuart in 1641. The decorations on the watchcase in painted enamel (email peint) by the Frenchman Henri Toutin depict mythological scenes that refer to the marriage.

From its inception, however, the Cabinet had incorporated both the Royal Cabinet of Curiosities and the Royer Collection, and therefore had a particular emphasis on non-Western art. The director of the Koninklijk Kabinet, R.P. van de Kasteele, even wrote to government officials stationed overseas, asking them to send him diplomatic gifts and curiosities for the collection. Because of this emphasis, Dutch decorative arts were not an important part of the Royal Cabinet’s collection unless they had a particular historical significance. As the century progressed, the concept of the Koninklijk Kabinet as a rather full cabinet of curiosities was criticized more and more. One piece of criticism reads: “The saddest part [of the Mauritshuis] is the pawnshop on the ground floor, which has been surrendered to decay.” These rather venomous words were written by Victor de Stuers, in his derisory article “Holland op zijn smalst” (“Holland at its most narrow-minded”), in which he criticized the way the Dutch government dealt with its cultural heritage. Shortly after the publication of “Holland op zijn smalst” De Stuers was given the power to change this, for in the wake of the article, he was appointed to a position that one might call “senior arts councilor,” in which capacity he founded the successor to the Royal Cabinet: the Nederlandsch Museum voor Geschiedenis en Kunst (Dutch Museum of History and Art) in 1875.

The new museum was to display both decorative arts and objects related to Dutch history. These were collected and displayed in more or less “antiquarian fashion,” meaning that their cultural and historical significance was of prime importance. A suitable building was found at Prinsegracht 71 in The Hague, and the government provided an annual budget. Parts of the collection of the Koninklijk Kabinet were incorporated into the new museum, which was very much a pet project of De Stuers. Many of the non-European collections became part of the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde (National Museum of Ethnology) in 1883.

The Rijksmuseum

In 1872 the Dutch government commissioned the building of a new national museum in Amsterdam: the Rijksmuseum. It was not until 1877, however, that the Minister of Culture decided that the Nederlandsch Museum should also be housed in the new Rijksmuseum building. In 1883 its collections were moved and by 1887 most of the galleries had opened, two years after the Rijksmuseum of Paintings. Like the Printroom, the Nederlandsch Museum was to become a separate museum under the direct governance of the director-general. The Nederlandsch Museum was housed on the ground floor of the building, together with the Printroom’s galleries. The majority of the galleries were installed more or less as period rooms featuring art from the Middle Ages to the seventeenth century. Many of the galleries contained architectural fragments from churches and houses, which were supplemented by smaller objects from different periods in display cases. The walls were painted, sometimes with copies of existing wall-paintings from chapels, but more often with interpretations of decorative elements that were intended to complement the objects shown. Other galleries had more specific themes, such as those that housed historical memorabilia and relics, many of which had come from the Royal Cabinet. According to the 1887 guide, the ceramics galleries were not yet finished.

On the Shoulders of Giants. KOG

This is the institutional side of the early history of the decorative arts in the Rijksmuseum, but even before De Stuers wrote “Holland op zijn smalst,” the preservation of the Dutch national heritage had become a pressing issue for a larger group of citizens. Several private initiatives had made a case for the protection of antiquities. The Royal Antiquarian Society (KOG) was among the first and most important. The society was founded in 1858 to “advance the knowledge of antiquities, particularly as a source for history, arts and the applied arts.” Through gifts and purchases the society built up an important collection of mostly Dutch antiquities and set up, not without difficulty, its own museum in Amsterdam. When it became clear that the Nederlandsch Museum would be moved to the capital, the KOG decided to lend large parts of its collections to that institution. The KOG was then and is now one of the Rijksmuseum’s most important lenders of both decorative arts and historical objects. Even among the Society’s earliest acquisitions, we find objects of great importance. On its first foray into the art market, the Society bought a number of significant pieces at the sale of the Moyet Collection in 1859. One such acquisition was a panel of Lydian stone inlaid with mother of pearl, made by the Amsterdam artist Dirck van Rijswijck. Van Rijswijck’s work was so admired in the seventeenth century that Joost van den Vondel wrote a poem about it. From the same auction also came the co-called Nassau Tunic, made for the funeral of Frederik Hendrik of Orange-Nassau on 10 May 1647. The Society also functioned as an intermediary through which private collectors could donate antiquities. Donating to the KOG was not the same as donating to the Rijksmuseum, but the two institutions had become closely connected. The KOG had its own galleries in the museum, as well as a boardroom and a separate entrance for members.

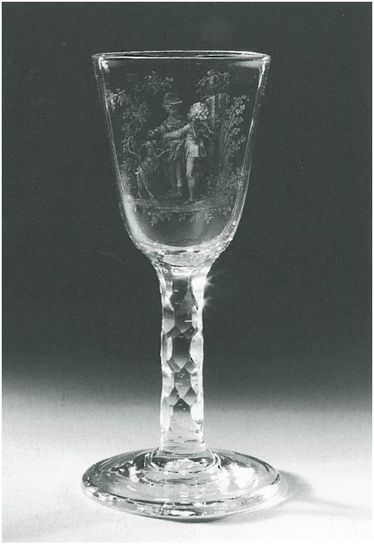

Enschedé

The early history of the Nederlandsch Museum also included a number of collectors who, by donating their collections directly, provided the basis of whole fields within the department of decorative arts. One such collector was Adriaan Justus Enschedé. Born into the famous Haarlem publishing family, he not only ran part of the family firm but was also a judge, archivist of the city of Haarlem, board member of the Teylers Museum, and one of the founding members of the KOG. Since childhood he had quietly collected old glasswork in his spare time. Despite his ties to the KOG, he decided to bequeath his collection directly to the Nederlandsch Museum, with whose staff he was in close contact. In 1893 none other than Barthold van Riemsdijk drew a portrait of Enschedé. At this time Van Riemsdijk was deputy director of the Nederlandsch Museum and would later become director-general of the Rijksmuseum. His personal acquaintance with the staff was very important for the development of Enschedé’s collection. In an article about the bequest, Van Riemsdijk explains how Enschedé and the museum were in close contact whenever important glasses came up at auction. He even describes how the museum sometimes refrained from bidding, knowing that the glasses Enschedé bought would one day be theirs. Such dealings would be frowned upon nowadays, but they were common practice at the time. An example of this was the Abels sale, held at Frederik Muller in 1894. Van Riemsdijk wrote to De Stuers after the sale: “Almost all the beautiful Wolff glasses were bought by Enschedé, two of them cost 100 guilders each. A number of the twenty-four glasses will be transferred to us.” David Wolff was one of the most important glass engravers in the Netherlands in the eighteenth century. The technique in which he worked, known as stipple engraving, became synonymous with his name. Both of the 100-guilder glasses can be traced to the Rijksmuseum’s collection. One shows two putti drinking, the other a pastoral scene.

The showcase with seventeenth-century diamond-point engraved glasses – featuring in the seventeenth-century galleries – illustrates the importance of several of the early benefactors of the collection (discussed above). No fewer than fifteen glasses came from the Koninklijk Kabinet van Zeldzaamheden. Most of these are glasses and bottles engraved by the Leiden cloth merchant Willem van Heemskerk. They were bought by Willem V at the estate sale of Van Heemskerk’s grandson in 1771. Nine glasses were either donated to or purchased by the KOG and are on loan to the Rijksmuseum. Five glasses came from the Enschedé bequest and thirteen glasses were either donated to or purchased by the Nederlandsch Museum or its successors.

Loudon

Like the glass collection, the collection of Delftware also has one particularly important founding father, but his collection came to the museum in a way that was completely different from the route taken by the Enschedé collection. John Francis Loudon was the son of a Scottish officer. He made his fortune as one of the founders of the Dutch Billiton Company, which mined ore in Indonesia. In 1869 he returned to the Netherlands, where he spent the rest of his life. Between 1869 and 1878 Loudon swiftly acquired an impressive collection of Dutch Delftware. In this case, however, it was not the collector himself who donated the collection to the museum, but his nephews and nieces, who did so in memory of their uncle, twenty-one years after his death.

The gift was subject to two conditions:

- That the donors would be exempt from paying inheritance tax.

- That the collection would be properly displayed.

The second stipulation was intended to ensure that the collection would remain accessible to the public. Hugo Loudon wrote the following to Aart Pit, then director of the Nederlandsch Museum: “I do not want to be completely dependent on the director of the Nederlandsch Museum. I know your point of view, but who will guarantee that a successor will not value old Persian or old Chinese ceramics or porcelain more and relegate the collection of Delftware to a back corner?” This is a touchy subject, particularly when donations of larger collections are involved. The donors’ wish to ensure the visibility of the collection is entirely understandable. But it is equally understandable that the museum would hesitate to accept overly stringent terms that would prevent flexibility in the handling of the collection. An agreement was reached in 1916 and the collection was displayed in the recently finished ceramics gallery, in new custom-built display cases. Here we see a system that differs from the way the collections were organized in the early years of the Nederlandsch Museum in the Rijksmuseum. The antiquarian vision of De Stuers was slowly making way for the more stylistic – or sequential – approach of director Aart Pit. Pit wanted to display art-historical sequences of objects, grouped according to period and medium. But he also fought against the rather invasive mural decorations devised by the architect Pierre Cuypers, and disapproved of displaying casts or reproductions to fill in gaps in the collection.

This had been common practice under De Stuers. Interestingly enough, under De Stuers the Nederlandsch Museum had been subjected to roughly the same criticism – i.e. that it had become antiquated – that he himself had leveled against the Koninklijk Kabinet. In 1926 the moment feared by the Loudon family had finally come: the ceramics gallery was given a new function and the Delftware was moved. The family did not need to be concerned about diminished visibility, however, because the collection now came to occupy pride of place in the Gallery of Honour.

Moving the Loudon collection to the Gallery of Honour testified to the collection’s importance, but it was also a means of breaking up the church-like appearance of the gallery and creating smaller, more intimate spaces. This transformation was part of greater changes in the museum. In 1922 Frederick Schmidt-Degener had become director-general of the Rijksmuseum. His mission was to bring about greater unity between the different departments of the museum. As part of his reorganization, the Nederlandsch Museum was dissolved in 1927, and sculpture and the decorative arts were separated from the historical objects. This allowed Schmidt-Degener to create a more aesthetic display throughout the museum. His approach was less antiquarian, but also less rigidly serial. Historical objects were installed in their own galleries, separate from the rest of the collection. Today the most important pieces of the Loudon collection are displayed in the gallery devoted to the arts during the reign of William and Mary.

Smaller in number

This gallery also contains a stately bed made in the style of Daniel Marot, William’s court architect. The bed exemplifies another kind of donation, where an individual object has a decisive impact on a part of the collection. Dutch furniture and silver are areas where the nature of the objects makes it harder for individuals to assemble a large collection of museum quality. In the case of furniture, this is due to the size of the objects. For silver it is more difficult to give one overriding explanation, but an important factor seems to be the fact that many pieces of domestic silver were passed down in families and used, rather than collected, until well into the twentieth century. So even though it is harder to pinpoint a single founder of these collections, they have nevertheless been shaped by individual donations of important pieces and many family heirlooms.

In 1925 the Minister of Culture received a letter from the secretary of Ph. Baron van Pallandt van Eerde in Ommen, offering the Rijksmuseum a stately bed belonging to the Pallandt family, which was then still at Eerde Castle, near Ommen. Some weeks later, director Schmidt-Degener wrote to the minister, saying that he was so keen to add the bed to the museum’s collection that he would be happy to accept it even though he knew it only from a photograph. After the war, the museum lacked a proper place to display its holdings of decorative arts. The addition of the Mannheimer Collection had greatly strengthened the collection of decorative arts, but since Mannheimer did not collect Dutch decorative art, I can do no more than mention his name here. Under director David Roëll the courtyards were closed and turned into gallery spaces; the Eerde bed was displayed in one of these new spaces. It was shown together with d’Hondecoeter’s Contemplative Magpie (1678) and the Hannart mirror, just as it is currently displayed in the William and Mary – a reminder that not everything in the New Rijksmuseum is completely new. Later the Rijksmuseum also bought four tapestries from Eerde Castle, after having them on loan for a number of years.

Adam van Vianen (1568/1569-1627), Cup with a bowl in the shape of a large shell, 1625

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Another example of an object that came to the museum through older ties is a cup made by the Utrecht silversmith Adam van Vianen. It was donated to the Rijksmuseum in 1948 by Marianne Nathusius. It is said that this gift was a token of gratitude for the care the museum had taken of her collection during the war years. Nathusius had had a number of silver plaques on loan to the museum since 1925. During the Second World War, even more of her collection ended up in the museum. Interestingly enough, the piece that she donated had not been part of an earlier loan. Plaques, either silver or lead, were exempt from the previously mentioned conditions placed on donations of silver. These specific cabinet pieces were collected as early as the seventeenth century. Marianne Nathusius’s silver most likely came from the collection of her first husband, Maximilian Ernst Fuld. After her death in 1951, the family sold the collection and the museum was able to buy two of the plaques that it had previously had on loan. Two other pieces ended up in the Centraal Museum Utrecht.

To summarize: the first institutional help for the newly founded Nederlandsch Museum came from the KOG. Both Loudon and Enschedé were collectors who had a decisive influence on particular parts of the collection. The bed from Eerde Castle and Marianne Nathusius’s silver have shown how individual donations helped shape the face of other parts of the collections. The last example I would like to give is a donation of yet a different kind, from the collection’s more recent history.

In 1978 Carly Jaffé-Pierson donated to the Rijksmuseum the collection of fifty-four pieces of Empire silver owned by her late husband, Paul Joseph Jaffé. The donation was an important incentive for the collection of nineteenth-century decorative arts, which was still in its infancy. Moreover, in their joint will the couple set up a foundation that has supported acquisitions by many museums, including the Rijksmuseum. This relatively small foundation with short lines of communication made a real difference on many occasions: a number of silver objects in the Rijksmuseum’s collection come to mind, as does the painting by Jacob van Ruisdael that was acquired by the Amsterdam Museum in 2008.

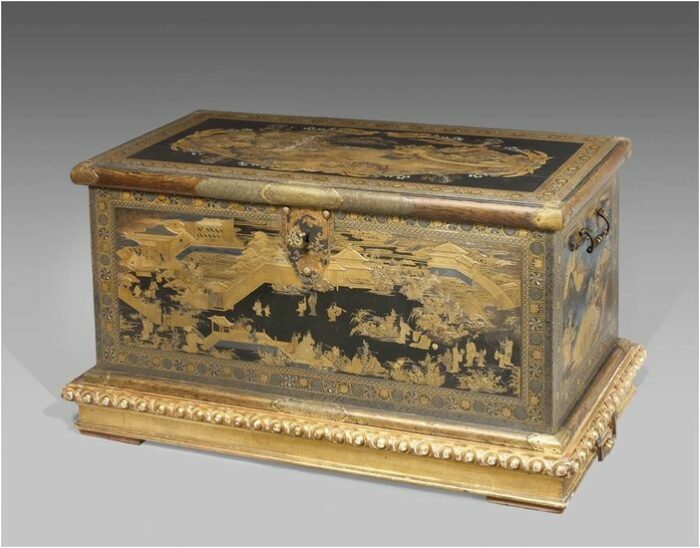

Last April the Rijksmuseum appealed to the foundation for a contribution in aid of its acquisition of a seventeenth-century Japanese lacquer chest. This so-called Amsterdam Chest is part of a group of only twelve pieces of Japanese lacquerware of the highest quality, made for the European market. It has an impeccable provenance, having had such distinguished owners as Cardinal Mazarin, William Beckford and the Duke of Hamilton. It disappeared from the art-historical radar until it turned up in France, in a private collection where it had been used as a liquor cabinet. The board of the foundation, acutely aware of the extraordinary importance of the piece, made a remarkable decision: it would make its entire capital available for the acquisition of the chest – a courageous decision that heralded the end of the foundation.

The Rijksmuseum’s collection of decorative arts has had its own history and its own champions. These private collectors have shaped the collections, enabling the museum to build on their passion by making further acquisitions. They truly are the giants on whose shoulders we stand. As a curator of decorative art and a member of CODART, I hope you have found it meaningful to hear about these collections of a different but equally important branch of Dutch art.

Femke Diercks is Junior Curator of Glass and Ceramics at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. She has been a member of CODART since 2009.