This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 1 Autumn 2012

Most CODART members are familiar with the Detroit Institute of Arts’s collection of early Netherlandish paintings and seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish paintings. For many a curator of Dutch and Flemish art, Detroit is Bruegel’s Wedding Dance, Rembrandt’s Visitation or Ruisdael’s Jewish Cemetery. The museum’s holdings of seventeenth-century Dutch paintings, the great majority of which are by signature artists of the Golden Age, is one of the larger collections of its kind in the United States.

Less well known are the DIA’s rich and varied holdings in sculpture and decorative arts from the Low Countries, from the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century. With the exception of the Arenberg Lamentation (fig. 1), few can readily identify significant works in the collection that are not paintings. But as an encyclopedic museum with more than 60,000 works of art, including a highly regarded collection of textiles numbering over 6,000 pieces, it comes as no surprise that the Low Countries’ achievements in the textile arts are well represented at the DIA. Of the almost 700 pieces of European lace in the permanent collection, more than 300 are Flemish. Another great strength is European tapestry, which is dominated by Flemish and Franco-Flemish examples. Of the eighty-one weavings, fifty were woven in one of the major centers of the Low Countries. Sculpture, glass and ceramics are less comprehensive, but notable examples from the Low Countries enrich the museum’s overall breadth and depth in European sculpture and decorative arts. Much of this area of the collection from the Low Countries is understudied; in what follows, I highlight several key objects, including recent discoveries.

1. Master of the Arenberg Lamentation, Arenberg Lamentation, ca. 1470-80, oak with traces of polychromy, 88.3 x 141.6 x 24.8 cm

Detroit Institute of Arts

No work of art better illustrates the Southern Netherlandish sculptural tradition than the Lamentation (1470-80), which was once part of the prestigious collection of the Dukes of Arenberg. Acquired on the heels of the 1960 landmark exhibition, Masterpieces of Flemish Art: Van Eyck to Bosch, the Lamentation is arguably the most important extant example of Netherlandish wood sculpture from the second half of the fifteenth century. Carved from three blocks of oak, the grouping shows Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus carrying Christ’s body to the sepulcher. The Lamentation is exceptional in its quality, size and mastery of execution. Despite having had its polychromy stripped, the work remains highly charged and deeply moving – a testament to sculpture’s unparalleled capacity to trigger empathy.

When the grouping was first published in 1919, it included a fourth block of wood with an additional figure of a bearded man. That figure, the whereabouts of which have been unknown since the object was acquired from Rosenberg & Stiebel in 1961, miraculously surfaced on the London art market in October 2011. The museum quickly moved to purchase the statuette; its discovery and subsequent acquisition is of enormous consequence for the museum and the field.

By contrast, an exquisite boxwood miniature Triptych (ca. 1520) (fig. 2), acquired in 1979 from the distinguished collection of Ernest Brummer, exemplifies the late medieval tradition of microscopic boxwood carving for which the Duchy of Brabant served as a major center. This tour de force of carving is only nine inches high, including its base. The central portion combines a Nativity scene with an Annunciation to the Shepherds, while the left shutter shows an Annunciation, and the right, a Presentation in the Temple. An Adoration of the Magi is carved in high relief in the foot below. Together, the Arenberg pieces and the Triptych testify to the extraordinary heights of virtuosity attained by Brabantine artists working in wood.

- 2. Unidentified artist (Brabant), Triptych, ca. 1520, boxwood, 22.9 x 13.6 cm Detroit Institute of Arts

- 3. Unidentified Artist (Utrecht), Pax, ca. 1450-75, ivory, 12.1 x 8.9 x 1 cm Detroit Institute of Arts

Northern Netherlandish sculpture is superbly demonstrated by an ivory Pax (fig. 3) made in Utrecht and dating to the third quarter of the fifteenth century. Sensitively carved, the convex Pax showing the Virgin and Child flanked by Saint John the Baptist and Saint Catherine is one of a group of eleven ivory reliefs defined most notably by their crosshatched grounds. A related object is a Polyptych with the Virgin and Child and Scenes of the Life of the Virgin, made from bone, wood and elephant ivory. Also a product of Utrecht and datable to between 1450 and 1475, the polyptych was catalogued as a northern Italian product of the Embriachi workshop at the time of its acquisition in 1923. The two objects contribute meaningful breadth to the museum’s collection of Gothic ivories and bone carvings, which is the third largest in the United States.

The extensive holdings in Flemish tapestries constitute the museum’s most important cluster of decorative arts from the Low Countries. As is typical of many American collections of European tapestries, the collection was formed primarily between the 1920s and the 1960s, under the tenure of Adele Coulin Weibel, the museum’s curator of textiles from 1927 to 1960. The more than fifty pieces of Flemish origin date from the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries and illustrate the history of artistic styles and major weaving centers throughout the Low Countries, the hub of European tapestry production. Noteworthy late medieval and Renaissance examples include a Millefleurs Tapestry with the Arms of the Brachet and Other Families of Orléans, Blois and Anjou (ca. 1500-20), an early sixteenth-century Brussels group of four tapestries referred to as the “Virtues and Vices” set, a Triumph of Spring from the “Triumph of the Seasons” series, woven in Bruges, and a Brussels Saint Paul before Porcius Festus, King Herod Agrippa and His Sister Berenice from the “Saint Paul” series, designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst. A delightful eighteenth-century Brussels example is the Don Quixote and the Windmills, from the popular “Don Quixote” series, woven between 1715 and 1747 to designs by Van Orley and Coppens in the Leyniers-Reydams workshop.

4. Brussels, The Captive Rulers , from “The Deeds and Triumph of Scipio Africanus,” ca. 1660, tapestry

Detroit Institute of Arts

This area of the collection is ripe for further study. In August 2009 a seventeenth-century weaving of major importance was discovered when it was unrolled for photography: a tapestry of The Captive Rulers (fig. 4) from “The Deeds and Triumph of Scipio Africanus.” Previously misidentified as a generic Roman Triumph woven in the Brussels workshop of Franz van den Hecke, the tapestry belongs to a huge set commissioned by Don Luis Francisco de Benavides Carillo de Toledo, Marquis of Caracena, and Governor General of the Spanish Netherlands from 1659 to 1664. Documents indicate that Benavides’s set comprised thirty-nine pieces altogether, with no fewer than fourteen large historiated pieces. Eight of the fourteen have now been located throughout Europe and South America, with the Detroit piece being the most recent discovery. Although Benavides’s coat of arms is no longer visible because the borders are lost, the motto – “Nisi dominus aedificaverit domum, in vanum laborarunt qui aedificant eam” – is still extant. The tapestry was most likely woven in Brussels around 1660. Whether or not it was woven in the workshops of Jan van Leefdael, Geraert van der Strecken and Hendrik I Reydams, following the three in the Toms Collection, Lausanne, remains a question mark because of the lost borders. The tapestry’s discovery was a great coup. Apart from its distinguished provenance, it shows off the splendor of Flemish Baroque tapestry. It is the museum’s only weaving enriched with gilt-metal-wrapped thread.

5. After Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, Last Supper, 1514-25, colorless glass, vitreous paint and silver stain, 1.3 x 23.8 cm

Detroit Institute of Arts

The DIA can lay claim to the most significant collection of stained glass in the United States after the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Pitcairn Collection, Glencairn, Pennsylvania. While the museum’s greatest strength lies in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century examples from German-speaking lands, one should not overlook three prominent examples from the Low Countries, including a painted roundel of the Last Supper (fig. 5), after a design by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, a Flight into Egypt, attributed to the Master of the Seven Acts of Mercy, and a panel of a Huntsmen and a Dice Thrower after Dirck Crabeth. Particularly noteworthy in its meticulous application of silver stain is the Last Supper: the effect is intense. All three were acquired at the same time in 1936 from the leading dealer of medieval and Renaissance stained glass, Thomas and Drake. A fourth panel, a quatrefoil roundel originally thought to be the product of a Netherlandish workshop, was correctly reattributed in the mid-1980s as Middle Rhenish. The museum also possesses a set of five large-scale rectangular windows from Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire, the origins of which remain debated. Recent research has indicated that the windows are most likely from Cologne, but it is difficult to rule out the strong possibility that they might be the work of glaziers from the Lowlands.

Seventeenth-century Dutch decorative arts are relatively underserved in comparison to the museum’s collection of paintings from the same period. In fact, it is a major area of potential growth. With the exception of a Tulip Vase (1690-1700), attributed to De Grieksche A Factory, and a delightful Pair of Shoes (ca. 1700), attributed to De Dobbelde Schenckan Factory, Dutch Delftware is poorly represented. Nevertheless, one can point to two handsome silver beakers by the Hague silversmith Adam Loofs (active 1680-1710). They were added to the collection in 1971 as part of a larger bequest from Robert H. Tannahill and catalogued as a pair of tumblers. It has been suggested that they are actually nesting beakers, since one is slightly smaller than the other. Their coat of arms awaits identification.

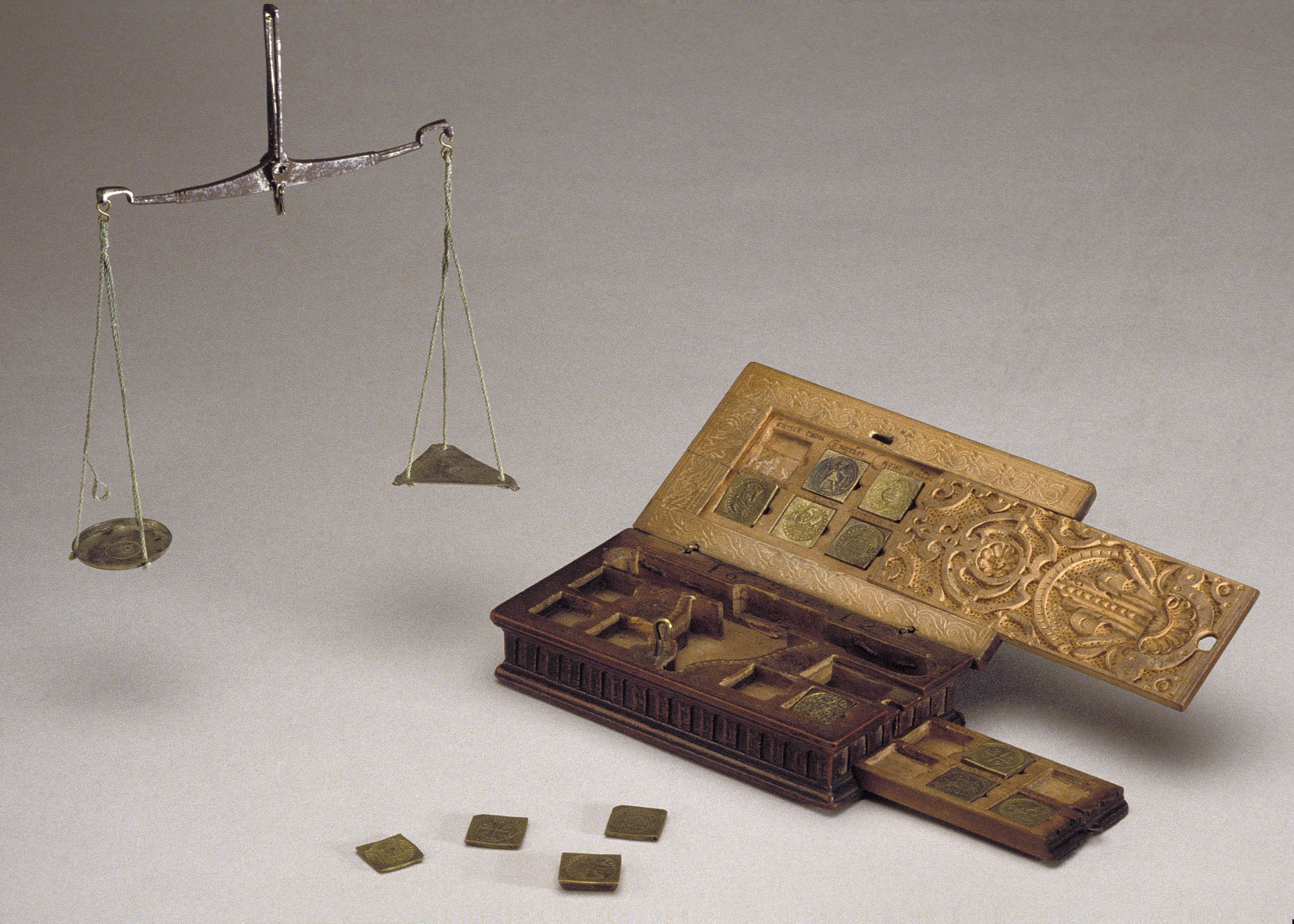

An unusual but noteworthy piece to end on is the 1612 Box of Coin Weights and Scales, also from the estate of Tannahill (fig. 7). Such kits were essential to early modern European merchants, who needed to calculate the rate of exchange for foreign currency, and assure themselves that the foreign coins they were offered were, in fact, legitimate. The box is marked with the sign of an unidentified Cologne master carpenter, but fourteen of the thirty-one weights contained within were hand struck by the Amsterdam instrument-maker Guilliam de Neve (ca. 1600-1654). Each weight is stamped with the reproduction of the coin whose weight it represents. The majority of the weights represent coins in circulation in the Netherlands in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. Most likely, the box was carried and used by a merchant conducting business in the environs of the busy port of Amsterdam.