On 17 January 2021, having traveled some 16,000 miles around the globe, the last of sixty European masterworks from the Indianapolis Museum of Art returned safely to the loading dock of their permanent home. Their return from China was met with relief by many IMA staff members, myself included, as the exhibition had encountered both challenging obstacles and gratifying successes that we could never have imagined a year prior.

The impetus for the exhibition was to make some of the great Old Master treasures in the IMA’s permanent collection available to new audiences, at a time when many of our European galleries were closed to the public. In summer 2018, the museum began a four-year renovation and reinstallation of the Clowes Pavilion and adjoining galleries, where the core of the IMA’s collection of European art has traditionally hung. Instead of putting so many works in storage, we approached venues around the world that would have an interest in exhibiting a substantial group of works ranging from fourteenth-century panel painting to Impressionist landscapes. Though the exhibition spanned a very broad range of time and geography, nearly a quarter of the exhibition was devoted to seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish works, reflecting one of the great strengths of the museum’s collection and strong interest from the public.

Quite unexpectedly, the greatest enthusiasm for the exhibition came from provincial venues in China. Introductions and meetings with our counterparts at various museums were brokered by a Chinese consultant who served as intermediary and occasional translator. While names like Rembrandt and Rubens were already familiar to museum-going audiences in Beijing and Shanghai, museums in the provincial capitals of Guangzhou, Changsha, and Chengdu expressed keen interest in presenting high-quality masterworks in conjunction with a broad overview of European art history. After welcoming a delegation from the Hunan Museum to Indianapolis in October 2018, a memorandum of understanding was signed and negotiations for the tour began in earnest.

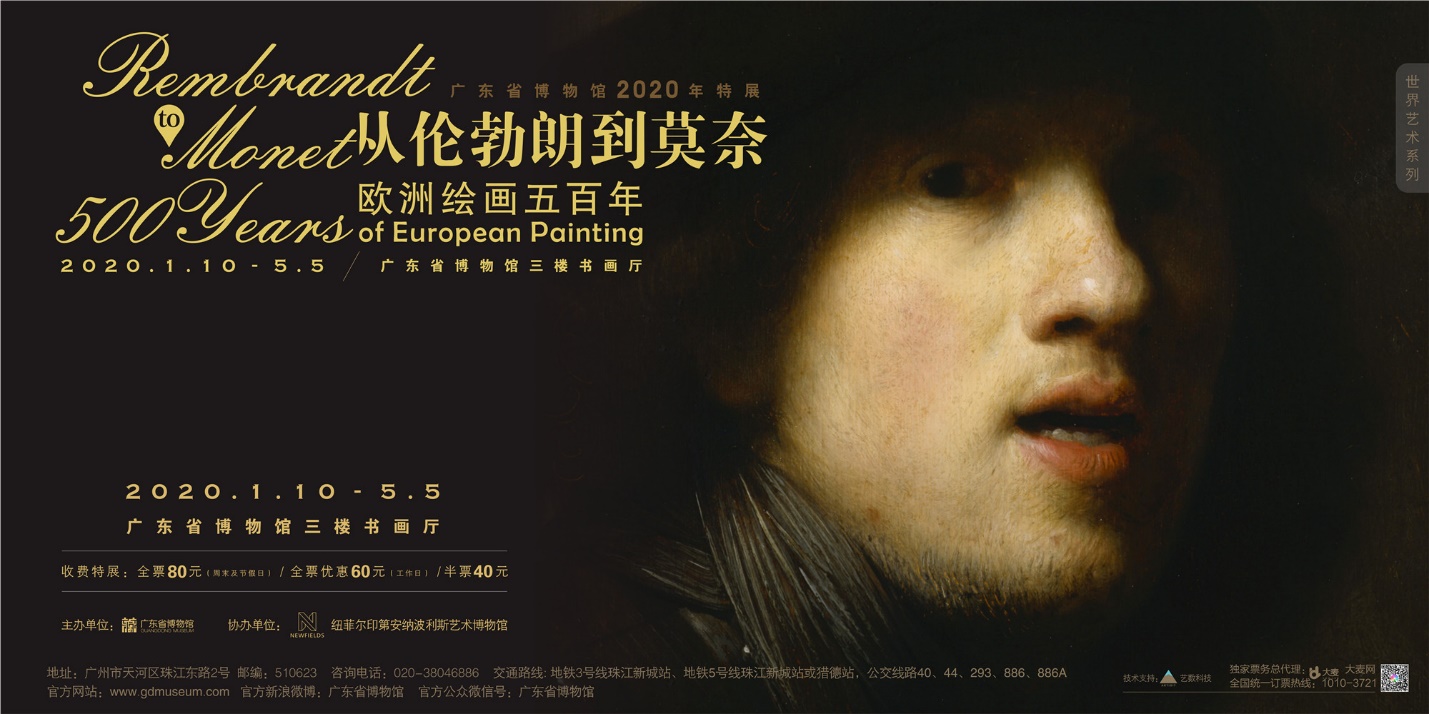

1. Marketing poster from the Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, featuring Rembrandt’s Self-portrait for the exhibition Rembrandt to Monet: 500 Years of European Painting

Our primary challenge in curating the exhibition lay in succinctly narrating some of the major art historical developments across the centuries for viewers with little or no familiarity with European art. The difficulty was particularly acute with respect to Netherlandish art: how do we convey the subtleties of genre and landscape painting, for example, or the huge implications of oil-based paint for the art of the region? To what degree must we delve into aspects of Christian theology and confessional divides in order to sufficiently interpret these works for our target audience?

-

2. Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), The Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, ca. 1617

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herman C. Krannert, 58.3

-

3. Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Triumphant Entry of Constantine into Rome, ca. 1621

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2001.237

Part of the solution hinged on the exhibition’s organization into seven thematic groupings, including sections devoted to religious works, still life, landscapes, and two distinct categories of portraits. (The final two categories were broadly chronological and focused exclusively on nineteenth-century works.) The choice of themes based on subject matter allowed for greater flexibility across geographic and temporal boundaries, while also making for more coherent and easily-explained groupings of paintings. Each section was anchored by representative works by renowned masters. Rembrandt’s early self-portrait, one of the best-known paintings in the Clowes Collection at the IMA, served as a natural focal point for the section on portraiture—in fact, its remarkable virtuosity and immediacy led the exhibition’s first venue, the Guangdong Museum, to use it to advertise the exhibition as a whole (fig. 1). Van Dyck’s splendid, early canvas depicting Christ’s entry into Jerusalem (fig. 2) highlighted the legacy of classical antiquity in the Christian art of Northern Europe, as did Rubens’s oil sketch depicting the triumph of Constantine, Rome’s first Christian emperor (fig. 3). The section devoted to landscape featured several Dutch and Flemish treasures, including Meindert Hobbema’s spectacular Water Mill and Jan Brueghel the Elder’s River Landscape (fig. 4).

4. Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625), River Landscape, 1612

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Clowes Collection, 2000.343

5. Willem Kalf (1619-1693), Still Life with a Chinese Porcelain Jar, 1669

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Mrs. James W. Fesler in memory of Daniel W. and Elizabeth C. Marmon, 45.9

Several of the show’s main categories (landscape, religious art, portraiture) loosely paralleled established conventions in Chinese art, which we hoped would make them more easily appreciated by an audience largely unfamiliar with Western painting. In some instances, connections between East and West were purely adventitious but equally enlightening. Willem Kalf’s masterful Still Life with a Chinese Porcelain Jar (fig. 5) provided a welcome opportunity to discuss the global significance of Dutch trade networks, which linked Europe with Southeast Asia and made Amsterdam into a cosmopolitan center. The painting aroused considerable interest from visitors who could see for themselves the impact that Chinese export porcelain had on shaping European tastes in luxury goods during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties.

Initial public interest in the exhibition was considerable, judging from crude statistical measures, though the emergence of COVID-19 in China threatened many of our ambitions for the entire tour. The Guangdong Museum’s WeChat announcement for the show was viewed by a quarter million users in the first 24 hours, and some 8,000 tickets sold within one minute of their release online. The exhibition’s grand opening on January 10, 2020 was marked by considerable fanfare, including a special “unveiling” and installation of the Rembrandt Self-portrait that garnered attention from the Chinese press (fig. 6). Little could we have known that the museum would be forced to close to the public exactly two weeks later, a closure would endure for the next 55 days. This period was fraught with uncertainty and complexity: contracts had to be renegotiated and Chinese couriers recruited to take the place of IMA staff originally designated to shepherd the show to Hunan and Chengdu (and ultimately back to Indianapolis). Huge differences in time zones, national holidays, and cultural norms only added to the difficulties.

- 6. Unpacking and installing Rembrandt’s Self-portrait in front of members of the Chinese press, Guangdong Museum, Guangzhou, 9 January 2020

- 7. Visitors on a guided tour of the Rembrandt to Monet exhibition, Hunan Museum, Changsha, June 2020

Fortunately for everyone concerned, the provincial authorities allowed the Guangdong Museum to reopen on March 19—just as other museums around the world were closing. From the start, the museum strictly enforced daily attendance caps, timed ticketing, limited gallery occupancy, mask wearing, and social distancing. In order to offset the enormous numbers of lost visitors and revenue, the Guangdong Museum extended the show’s run for an additional twelve days. By its close, the total number of visitors stood at 56,582—less than a quarter of the anticipated figure, but a remarkable achievement given the formidable obstacles presented by the coronavirus. No closures hampered the exhibition in its final two venues, which were able to accommodate high numbers of visitors: the Hunan Museum welcomed more than a quarter million people, and the Chengdu Museum ended up with well over half a million.

8. One of several creative submissions by Guangzhou schoolchildren imitating works from the Rembrandt to Monet exhibition

More importantly—from a curatorial standpoint, at least—the exhibition appeared to elicit deep engagement with the works on view. Docent-led tours of the exhibition were often oversubscribed, with participants asking detailed and thoughtful questions about everything from painting technique to Christian iconography (fig. 7). Because so many local schoolchildren had been prevented from seeing the exhibition in person, the Guangdong Museum, in partnership with the Guangzhou Children’s Palace, hosted an event on International Museum Day (18 May) where children were invited to virtually “attend” the exhibition’s inaugural lecture. They were then invited to interact with the paintings by creating artworks of their own (fig. 8). The exhibition was popularized by a huge variety of novelties inspired by the works on view, ranging from a Nicolaes Maes-inspired pillow to Rembrandt-themed chocolates, which proved to be quite popular (fig. 9).

As we welcomed our paintings home, almost exactly one year after they had departed, the IMA had much to celebrate. Our dedicated registrars and exhibition staff had navigated one logistical hurdle after another, working tirelessly to bring the tour to a successful conclusion. The museum has since benefited from an enhanced international profile, particularly in China, where several venues have expressed hopes for future partnerships and reciprocal loans. In addition to meeting and working with wonderful museum colleagues in China, I have been thrilled by the hundreds of thousands of visitors who braved pandemic conditions to view the exhibition and learn more about Dutch and Flemish painting—moving testament to the power of great works of European art to captivate audiences from around the world.

Kjell Wangensteen is Associate Curator of European Art at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. He has been a member of CODART since 2017.