This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 3 Autumn 2013

When the young Belgian state saw its independence ratified by the nations of Europe in 1840, it celebrated this historic event in Antwerp with Rubens festivities mounted on a grand scale. The new nation yearned for great moments from its past that could legitimize its claim to independence. It was only natural to associate Rubens with the country’s history, since he had been the privileged court painter to Albert and Isabella, rulers of the principum belgarum.1 A court official and entrepreneur, Rubens embodied the cultural grandeur – recognized throughout Europe – of his generation.

This nationalization of Rubens occurred at the same time as another romantic phenomenon: taking the lead from the French writer, art collector and politician William Bürger (alias Théophile Thoré), the Dutch school of painting seceded from the rest of “les écoles du Nord.” In the words of Busken Huet, the North became “the land of Rembrandt,” whereas the South became “the land of Rubens.” Both of these artistic luminaries had their roots in what Friedländer called “Early Netherlandish painting” (“Altniederlandische Malerei”), a school of painting whose mystical background – the Devotio Moderna – had led it to develop a distinct world view in the fifteenth century. Its interpretation of the sensorily perceptible world as a reflection of the transcendental led it to focus on the descriptive and analytical image – an image of reality such as that seen in a mirror or later discovered in a camera obscura.2 This tradition gave rise in the sixteenth-century “école du Nord” to the genres in painting that are still propagated as a product of the Dutch school of painting. In “the land of Rubens” it was a different story. Rubens would reconcile the tradition of the Early Netherlandish school with the notions of the Italian Renaissance – whereby the world was viewed as through a window and the image distilled according to the art-theoretical principles of antiquity – which was necessary to the development of the fine arts in a way that met the requirements of good history painting. Rubens succeeded in this as none other: he translated the political ideology of practically every major European court into a visual idiom, and under his influence the Southern Netherlands became a center of absolutist and Counter-Reformationist picture production and export, with Antwerp as its flagship – the Hollywood, as it were, of the Spanish crown.

In the economic boom experienced by the young industrial nation of Belgium in the nineteenth century, Antwerp again played a prominent role as a harbor town, which evoked happy memories of its sixteenth-century golden age and the rule of the archdukes. Rubens is central to that story too, of course, but it is striking that during the Rubens celebration of 1877 – at which time he made his entrance into modern art history in the publications of Jos Van den Branden, Max Rooses and many others – his image shifted from court painter to the archdukes to standard-bearer of the Antwerp school of painting. Rubens was thus proclaimed prince of the Flemish school of painting, in the context of the Belgian nation, where the concept of Flemishness was gradually taking on a whole new dimension. One wonders what Rubens himself would have thought of this development. In other words, if Rubens is naturally associated with Flemish painting, what is meant by the term Flemish?

Since the Middle Ages, Flanders has been a mark of quality, particularly with regard to such luxury goods as music and art. Even in those days, artistic production was geared to export and, in Burgundy, attained unparalleled heights as early as the fifteenth century. This tradition continued at the court of the Habsburg king Charles V in Spain, where it was chiefly the Flemings who set the tone and affirmed their identity with the epithet “Flemish,” an example being the renowned “Capilla Flamenca.” But it was not only at the great courts of Europe where the Fiamminghi were active. Their art had its roots in the urban bourgeois culture of the merchants, shopkeepers and artisans upon whom the reputation of “les bonnes villes de Flandre” was founded. It was a cultural climate that was envied, both for its sometimes presumptuous opulence and for its display of power, but it was also derided for its independent view of life, a view that remained interwoven with the sense of reality intrinsic to city-dwellers but so often at odds with the refinement of European court culture, which was out of touch with the real world. It is a reputation to which Svetlana Alpers alludes in her essay “The Making of Rubens” but which is nowhere better visualized than in Victor Hugo’s “Notre Dame de Paris,” in which he presents the “Flemish ambassadors” with verve.3

As it turns out, many of those artists were not Flemings in the strict sense of the word; they were from Brabant, Holland or Hainault, for example, and much of their work had also originated elsewhere. It was the Italians, however, who invented the term Fiamminghi for the makers of high-quality art from the Low Countries. The image of “Flanders” was so strong, in fact, that it came to be used in the rest of Europe to designate – as pars pro toto – the whole of the Northern and Southern Netherlands.

Flanders could boast near-mythic fame in the field of painting, since it was considered the birthplace of a revolutionary new technique: painting in oils. The unprecedented possibilities and the results obtained with this technique boosted the development of European painting. Its discovery has traditionally been attributed to a Fleming, Jan van Eyck, the figurehead of fifteenth-century Flemish painting. He was not alone, however. In addition to Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes and Hans Memling, such Germans as Martin Schongauer and Albrecht Dürer were given a place in this row of Fiamminghi, which was, after all, not a strict geographical designation but a common denominator for the outstanding painting that flourished north of the Alps.

Rubens, too, was nicknamed “il Fiammingo” during his stay at the court in Mantua at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Though admittedly born in Siegen (Germany) of Antwerp parents in exile, Rubens was, strictly speaking, a Brabanter who was trained as a painter in Antwerp.4 He received his formal education as an artist from Otto van Veen, court painter to the archdukes, who had a broad humanist background. It was Van Veen who taught Rubens that the art of painting was based not just on expert knowledge and studio practice, but also on an understanding of art theory and an acquaintance with the “classics,” including both the art and literature of antiquity and the great masters of the Italian Renaissance. Van Veen acquainted Rubens with the court painter’s “code of conduct,” but he also left his mark on the style of the young artist – a style characterized by a distinct Italianate mannerism constrained by both his own studio tradition and Italian art theory of the Renaissance. This was the baggage Rubens took with him when he left for Italy in 1600, after enrolling as a master in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke. It was in this period that “il Fiammingo” went international: he honed his diplomatic skills on a mission to Spain, assimilated the Italian High Renaissance, immersed himself in the legacy of antiquity, and developed a style of his own – all of which enabled him to compete with his Italian contemporaries. He gave up his Gothic handwriting and adopted the elegant litera latina, the Italica. He changed his Christian name to Pietro Paolo – though his mother still referred to him in her will as “our little Peter” (“ons Peterken”) – and the Italian of those days became the language of most of his surviving correspondence. Rubens was a polyglot, and perhaps this, too, is one of his Flemish traits. His letters reveal that he was fluent not only in Italian and Dutch, but also in French, Spanish and Latin.5 His mother tongue and lingua franca, however, remained the dialect of his native Brabant. Not surprisingly, his most spontaneous letters were written in Dutch, which was also the language he used to make notes on his drawings and designs.

The brilliance of the international style that Rubens developed in Italy consisted of a curious combination of the qualities the Fiamminghi recognized in themselves and the power and insights of the Italian Renaissance. He thus contributed to the European Baroque in a way that no one else could match. To Rubens, the question of his Flemishness would probably have sounded absurd, for he thought of his artistry as continuous emulation – improving his own style and building on the achievements of others. This explains why he did not hesitate to make “improvements” to the drawings and paintings he collected by Old Masters and contemporaries alike. It also shows why he continued throughout his life to evolve stylistically, from the exploratory bravura of his younger years to the artistic virtuosity of his late work.

Bearing this in mind, it is interesting to examine the extent to which his “Flemish” heritage either helped or hindered him. This exercise may well prove worthwhile as a means of gaining insight into the evolution of the master’s stylistic idiom – even if his Flemish heritage was something he simply took for granted. There are indications, however, that he did give it some thought.

Jos Van den Branden relates with his usual enthusiasm in his Geschiedenis van de Antwerpse Schilderschool how “the great Rubens himself had paid splendid tribute to Quinten Metsijs.”6 In fact, the veneration of Metsijs was not just a question of cult worship. The confrères of the painters’ guild, and Rubens too, saw him as the founder of the Antwerp tradition of painting, which at this time was viewed as emulating the Flemish school of painting. By virtue of its position as the economic and artistic center of the sixteenth-century Low Countries, Antwerp had never been lacking in self-importance. It therefore viewed itself as the heir to the Flemish tradition of painting. In this context, the contribution by Max P.J. Martens and Nico Van Hout, titled “Dun ende spaerlyck,” is highly relevant.7 They de-regionalize the question of style surrounding the Fiamminghi by focusing on the painting technique that underpins the identification and characterization of “Flemish”: a tradition of painting that had developed in the Low Countries and, before the founding of the art academies, was passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth within the studios or by itinerant artists.8 This phenomenon shows that the study of painting technique can be viewed as a characteristic of the wide dissemination of technology and expertise in early-modern times.

-

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Elevation of the Cross, 1609-1610

Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp

-

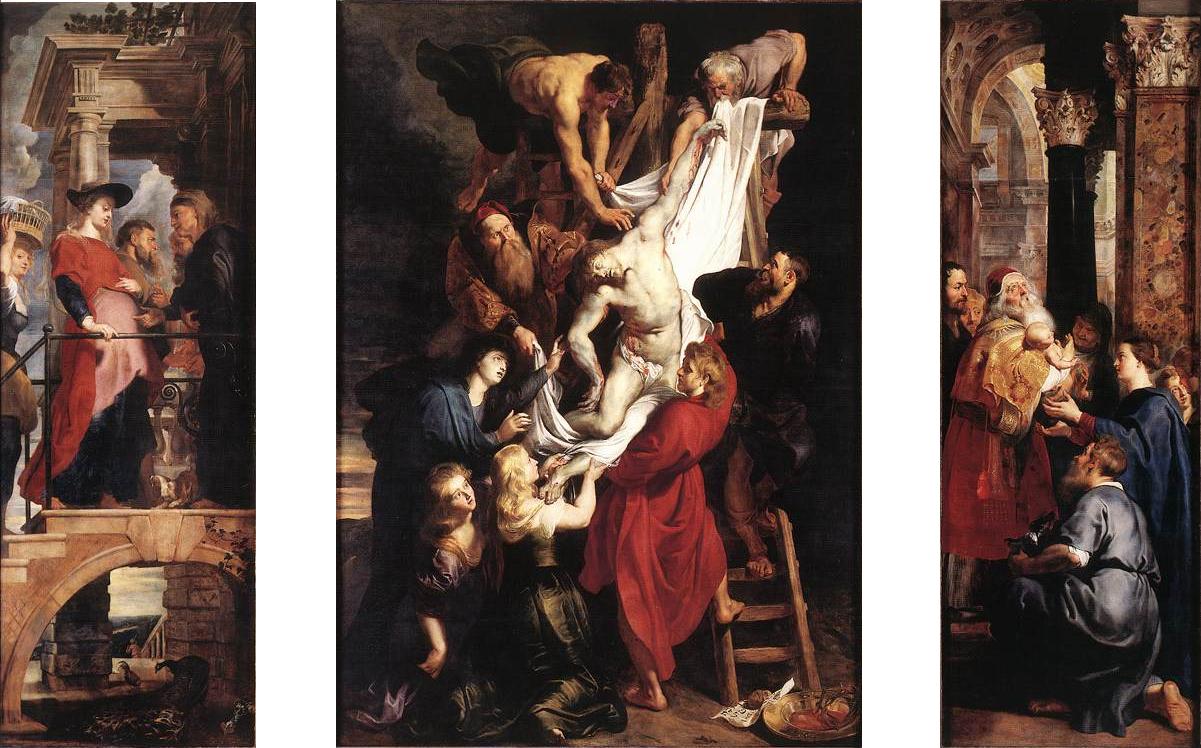

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Descent from the Cross, 1611-1614

Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal, Antwerp

It is clear that Rubens, once he had settled again in Antwerp after his return in 1609, introduced a fundamental change to the painting technique he had mastered in Italy. The phenomenon is nowhere better illustrated than in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, where we are presented with the confrontation between Rubens’s triptychs with the Elevation of the Cross and the Descent from the Cross. What strikes one is the adaptation of his pictorial idiom to a thin and sparing application of the paint layers, which lies at the basis of the transparent painting technique in which the masters of the North traditionally excelled. Rubens’s turnabout was probably also prompted by the insights acquired while working with Father Aguillonius, whose De opticorum Libri VI he illustrated. Moreover, his confrontation with the classicist style of the Northern masters on the journey he made in June 1612 must also have played a role. It is generally assumed that Rubens’s stylistic about-face was prompted by his success and his need to work more quickly in order to meet the growing demand for his work. He therefore reverted to the smooth, fluent brushwork developed before him by Frans Floris and Maarten de Vos, a style that was more suited to collaboration in a very busy studio.

Yet time and again it appears that Rubens nevertheless followed his personal artistic impulses, and, if he did in fact realize that he was the most important artist of his generation, he did so – after his return from Italy – from the perspective of his Antwerp context. He became integrated – sometimes with striking amicability – into the brotherhood of his fellow artists, with whom he collaborated in various ways: working with fellow painters in his studio; contributing to mega-projects, such as the pompa introïtus Ferdinandi and the Torro della Parada; participating in the guild; and by humbly declaring himself to be a craftsman in heart and soul in a letter to Peiresc on the occasion of his second marriage in 1630. To be sure, all the while he remained his own superior self, avoiding his civic duties and evading taxes whenever possible, and in doing so, not always showing his best side. Then again, collaborative projects such as those carried out with Jan Brueghel testify to remarkable engagement with his own Antwerp painters’ milieu.

-

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) en Jan Breughel de Oude (1568-1625), The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, ca. 1617

Mauritshuis, The Hague

-

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), The Fair, around 1635

Museé du Louvre, Paris

In her above-mentioned book The Making of Rubens, Svetlana Alpers tries to gauge Rubens’s “Flemishness.” She recalls how shocked Ruskin was in 1849 to see Rubens’s Village Fête in the Louvre, with its raw and coarsely realistic portrayal of drinking, dancing, courting and brawling peasants, who, like the swine in the foreground, behave like beasts in the mud. This unpolished sense of naturalism – that is to say, loutishness and lack of cultural refinement – is considered a Flemish characteristic with a long tradition.

Pieter Breughel II (1564-1638), Pieter Brueghel III (1589-1608), Fair of Saint George, seventeenth century

KMSKA, Antwerp

I am not very keen on the way Alpers associates the Flemish soul with coarseness and inebriation, but she has a point when she sees a Flemish approach in Rubens’s interest in the genre as such. It is easy to forget that the great master of Baroque history painting gave a considerable thrust to the development of genre painting, which – though nowadays automatically associated with Holland – actually arose in the South. It is remarkable how Rubens’s genre pieces rise above their art-theoretical limitations, as evidenced by his late landscapes. Even in his depictions of village fairs, the serenity of the landscape contrasts sharply with the human activity in the foreground. Here, too, Rubens relied on a tradition in which he was preceded by Pieter Bruegel. His close familiarity with it emerges from the passion with which he himself collected genre pieces, and the alacrity with which he made “improvements” to sixteenth-century paintings – such as his retouchings to Maarten van Cleve’s Feast of Saint Martin (now in the Rubenshuis) – testifies to his faith in the expressive power of genre painting. The presence of Northern masters in Rubens’s collection demonstrates that he recognized no such boundaries. It also makes clear that his interest in genre painting was primarily an artistic one, without the political undertones suggested by Alpers. After all, Rubens had the opportunity to make powerful political statements in his history paintings. The fact that his own political engagement, which was rooted in the Low Countries, often influenced his art is best shown by the written sources, and this has been done superbly by Nils Büttner in his book Herr P.P. Rubens, Von der Kunst, berühmt zu werden.9

Following in the footsteps of Alpers, Büttner sets out to discover what made Rubens so special. But instead of looking for signs of his Flemish grounding in the underlying iconographic messages in his work – which Büttner rejects as too speculative – his quest for Rubens’s nature involves thorough examination of the historical sources, which allows a more sound interpretation of his biography – i.e. career, social context and success as an artist. This leads him to confront Rubens’s utter devotion to his native city (once he had returned from Italy) and to examine the extent to which his success there rested on his Antwerp roots: the people, the culture and the social context of an urban bourgeoisie. His status as court painter and his marriage to Isabella Brant, daughter of the city magistrate Jan Brant, sooner reflected his distinguished origins than did his practice of the painter’s craft, which was not held in particularly high esteem. It has already been pointed out how Rubens sought affiliation with the guild, thus integrating himself in Antwerp society. For generations his family had been administering and leasing their properties, which was another means of engaging with neighbors and fellow citizens. As court painter and a wealthy burgher, he was well aware of his social standing and at times he naturally assumed an aristocratic lifestyle.

Rubens’s growing international reputation, his noble standing and his extensive travels were apparently no reason for him to distance himself from his Antwerp roots. Indeed, his héritage flamand was of a piece with the self-identification alluded to by Marguerite Yourcenar – for whom the Flemish school of painting was an inexhaustible source of inspiration – in the context of drawing up her Flemish family tree, in which the “peintre flamand” figures not only as the representative of an artistic tradition that contributed substantially to the development of the visual arts in Europe, but also as a family member referred to with pride.10 Rubens’s Flemish heritage is indeed remarkable, even when viewed in a European context.

Paul Huvenne is director of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. He has been a member of CODART since 1998.

Notes

1 The sovereign rulers of the Spanish Netherlands (1598-1622).

2 David Hockney, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the lost techniques of the Old Masters, London, 2001.

3 In “Notre Dame de Paris” Victor Hugo portrays the “Flemish ambassadors” on their 1482 mission in the midst of the squabbles of the notorious Paris public.

4 Carl van de Velde and Prisca Valkeneers, De Geboorte van Rubens, Ghent-Kortrijk, 2013.

5 Svetlana Alpers, The Making of Rubens, New Haven and London, 1996, p. 51.

6 Jos Van den Branden, Geschiedenis der Antwerpsche schilderschool, Antwerp, 1883, pp. 649-50: “The great Rubens himself had paid splendid tribute to Metsijs by purchasing for large sums of money the scarce creations of the smith-painter and giving them pride of place in his magnificent Kunstkammer” (“De groote Rubens zelf had Quinten Matsijs eene schitterende hulde gebracht door de schaarsche gewrochten van den smid-schilder tegen groote sommen aan te koopen en hun eene eereplaats te schenken in zijne prachtige kunstkamer”).

7 Max P. J. Martens and Nico Van Hout, “‘Dun ende spaerlyck’. Painting transparently in the Low Countries 1450-1650,” Symposium Embattled Territory: The Circulation of Knowledge in the Spanish Netherlands, Ghent, KANTL, 9-11 March 2011.

8 The Antwerp art academy was founded in 1663.

9 Nils Büttner, Herr P.P. Rubens, Von der Kunst, berühmt zu werden, Göttingen, 2006.

10 Achmy Halley and Sandrine Vézilier-Dussart, Marguerite Yourcenar en de Vlaamse schilderkunst, 2012, p. l.