The CODART Canon is an overview of the most iconic works of art produced by Dutch and Flemish artists before 1750. Among them is the woodcut Customs and Fashions of the Turks by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502–1550). It can be read as a pictorial travel journal of the Southern Netherlandish artist’s visit to Constantinople in 1533, showing the city’s architecture as well as its inhabitants and their traditions. Twenty years later, after Coecke van Aelst’s death, the drawings he had made on his travels were turned into prints and published by his widow Mayken Verhulst (1518–1600). We believe the series occupies a unique position in art history and has rightly been included in the Canon. Customs and Fashions of the Turks stands out from the other works in the Canon – especially the other eighteen works on paper – by virtue of its exceptionally large format. The ten linked sheets of paper extend to a total length of 4.5 meters. Because of this, very few series have survived in their entirety: only a dozen museum collections have a full set of the giant woodcut. The sheets are preserved there safely, either stacked or rolled up, which means that most of us have never seen the complete work in all its glory.

Fig. 1. Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), Customs and Fashions of the Turks (fragment depicting a wedding procession), 1553, woodcut, 292 x 460 mm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-OB-2304H)

Other large-scale works on paper present similar difficulties in terms of displaying them for museum visitors. Their delicacy and size mean they are usually hidden away in the depot. Jane Turner, former head of the Print Room at the Rijksmuseum, was determined to change this – for once she wanted to place these monumental works from the museum’s own collection in the spotlight. And rather than showing them in the expected surroundings, the intimate print rooms, she set her sights on the exhibition wing, with walls of up to 6.5 meters high – the perfect setting for the huge works on paper. The basic principle for the XXL Paper exhibition was that all museum visitors, whatever their age, would be spellbound by the display extending from floor to ceiling, whether or not they came armed with foreknowledge.

The key selection criteria were “large size” and “paper.” That meant that when we took over the XXL Paper project following Jane Turner’s retirement, these somewhat unconventional and challenging criteria of the exhibition concept guided our process. It meant looking at the collection with different eyes – an approach that led to surprising discoveries. Besides going through the regular boxes in the depots where the prints and drawings are kept, we also explored the largest drawers. We even pulled out the gigantic hanging racks in the Netherlands’ new Collection Center (CCNL), where we found a number of framed works on paper, including a number of composite prints, nestling among the numerous paintings. In the course of this preparatory work, some of the objects were unrolled, studied, and preserved for the first time. The result of all this work was a varied selection of prints, drawings and photographs from 1500 to the present day, each one with a length or width of at least 1.5 meters: the Rijksmuseum Print Room in its full breadth.

-

Fig. 2. Mattheus Borrekens (1615-1670) after Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641), Crucifixion, engraving, 1650, 1961 x 1257 mm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-OB-102.327)

-

Fig. 3. Attributed to Michiel Coxcie (1499-1592), Landing of Scipio Africanus at Carthage, ca. 1555, gouache on paper, 2480 x 2570 mm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-T-2004-1)

It seems that artists had many different reasons for choosing to work of paper on large format. Some objects were designed to depict legendary stories on an impressive scale, others to ensure that political messages were widely disseminated, to boost a city’s image, or to bring distant places closer. Paper was ideal for such purposes, since it was relatively cheap, light, and versatile. So, as we selected the works, we took care to include representative examples of all these various functions. The altarpiece with the Crucifixion that Mattheus Borrekens (ca. 1615–1670) engraved and published in 1650 consisted of eleven separate sheets that could easily be put together, mounted and hung (fig. 2). A perfect example of the democratization of religious art: it meant that these enormous devotional images were available to everyone – in parish churches and conventicles, in hospitals and in workshops. Because these large works on paper were usually glued and nailed to walls and doors, many of such ensembles are rare today.

Fig. 4. Robert Péril (active 1522-1536), Family Tree of the House of Habsburg (fragment), 1535, woodcut, 368 x 480 mm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-1927-426)

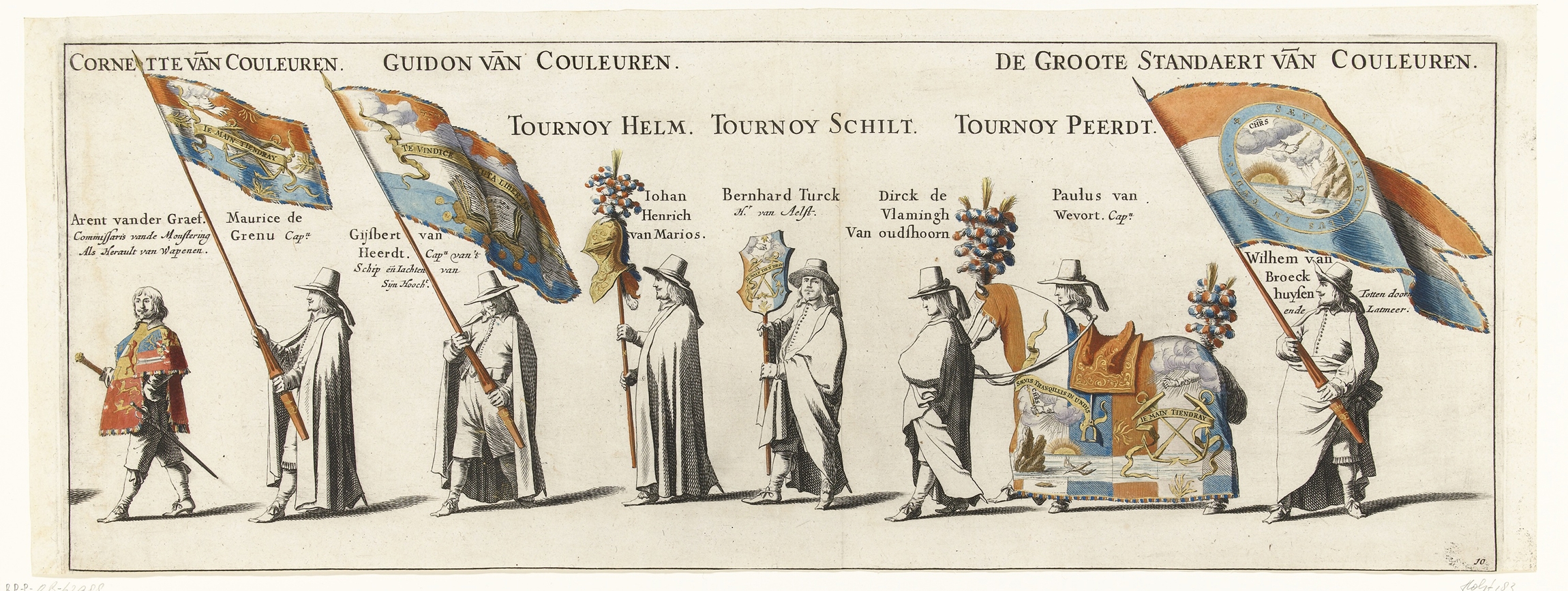

The same applies to preparatory or preliminary works. After all, the artist would often be unconcerned with the successive stages in the creation process: what mattered was the final result. Preparatory work was therefore often destroyed or cut up and reused. The exhibition nonetheless includes several examples – such as the cartoons with the designs for the stained-glass windows in the north transept of Utrecht Cathedral (1934) and those for St. Bavokerk in Haarlem (1541). Another exhibit, from the studio of Michiel Coxcie (1499–1592), is a design for a tapestry depicting the landing of Scipio Africanus at Carthage (fig. 3). The figures on the ship are almost life-sized, as a result of which they appear to directly engage the visitor. For the weavers, this cartoon, measuring 2.6 x 2.5 meters, served as a full-scale model, executed with astonishing precision in composition and use of color. The many small tears in the paper and the fact that the sheets were eventually lined demonstrate that the painting was constantly re-used. An example of an object without any artistic connotations is the map of the region known as Delfland Hoogheemraadschap. It was a masterpiece by the cartographer and land surveyor Nicolaas Cruquius (1678–1754). The 25 sheets made it possible to formulate and enforce policy. In the case of city plans and profiles, the large format often served a more promotional purpose: from about 1500, cities sought to put themselves emphatically on the map and display themselves in all their glory, for instance in council meeting rooms. Technical innovations, such as woodcuts and the possibility of using larger paper sizes, were key to these strategies. Propaganda intended to emphasize and validate power also played a role in the seven-meter-long family tree of Charles V (1500–1558), executed by Robert Péril (act. ca. 1522–1536) (fig. 4). Another example: the image of the funeral procession of Stadholder Frederick Henry (1584–1647) (fig. 5), which departed from the Binnenhof in The Hague for the Nieuwe Kerk in Delft on 10 May 1647, required 16 meters of paper to record the names of the hundreds of attendees. The only way to fit the procession into the museum’s Philips Wing is by displaying it above the doors and having it extend around the corner.

Fig. 5. Pieter Nolpe after Pieter Jansz. Post, Funeral Procession of Frederick Henry (fragment), 1651, etching, hand-colored, 203 x 550 mm

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-OB-67.988)

The difficulty of getting such monumental works onto the walls of the exhibition galleries should not be underestimated. Close cooperation with the art handlers and the team of paper conservators led by Idelette van Leeuwen (Head of Paper Conservation) was essential, and they were therefore closely involved from the very beginning. Even then, the project ran into numerous practical problems: doorways were too narrow, elevators too small, and traditional frames too constraining. For each object, suitable alternatives had to be found: such as Perspex, Velcro and cover strips. The preparations led to new, innovative solutions. Scaffolding and aerial platforms were not only used by art handlers, but even some conservators overcame their fear of heights and attended a training course that enabled them to work at great heights.

The exhibition design (fig. 6) by Irma Boom was another indispensable link in the process. The color and typographical design of the walls and captions were important factors in creating a unity between the great diversity of the works on show, without obscuring their individual characteristics. First, it was decided to display each exhibit’s dimensions boldly on the wall. The object information on the wall would not normally include information about its size, but in this case, the size is central to the exhibition. Visitors will therefore want to know exactly how large each work is, and how it compares in this respect to the others. In addition, it was decided to display the text labels on the walls on white A4 sheets of paper: this familiar size offers a welcome frame of reference. The walls’ green background proved to work surprisingly well with both the old paper and with modern inkjet printing, and therefore served as a refreshing way to provide continuity between the works.

Ultimately, of course, it is up to you to judge the final result. As the visitors to this exhibition, only you can determine whether all the plans made at the drawing board have the desired effect in practice. It goes without saying that you are warmly invited to visit XXL Paper this summer!

Maud van Suylen is Junior Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. She has been a member of CODART since 2018. Manon van der Mullen is Head of Collections and Research at the Dordrechts Museum in Dordrecht.