This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 3 Autumn 2013.

As soon as she completed her degree in art history at the KU Leuven in 1997, Véronique Van de Kerckhof started working as a research assistant at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium for the exhibition The painter and the surveyor: Brussels and the former duchy of Brabant. In 2000 she became an assistant curator at the Rubenshuis and in 2004 at the Museum Plantin-Moretus/Prentenkabinet, where she put together or coordinated several exhibitions. In 2008-09 she joined the team entrusted with preparing the opening of Museum M in Leuven. Since 2010 Véronique Van de Kerckhof has been director of the Rubenianum.

To begin with, would you please tell us about the origins of the Rubenianum and the collections it administers?

The Rubenianum came into being in conjunction with the opening of the Rubenshuis as a museum in 1946. As early as 1919, Antwerp specialists had pointed out the need for a center of excellence that would collect and make accessible all the information available on the art of Rubens and his time. Exactly fifty years ago, in 1963, this center came into being: the Rubenianum was established as an autonomous institution and from the start it had a world-class collection at its disposal, thanks to the scholarly legacy of Dr. Ludwig Burchard. The most important part of Burchard’s archive is his documentation on Rubens, which we have continued to augment for decades. It still provides the scholarly underpinnings of the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, the monumental catalogue raisonné of Rubens’s oeuvre. Soon after its founding, the Rubenianum grew into a renowned institution that welcomes anyone interested in consulting its rich holdings of documentation on Flemish art.

The Rubenianum is both a research institute and a center of excellence. How do the tasks of these two branches differ?

In my view, these branches do not actually differ. We do indeed take most of the responsibility for the center of excellence, while sharing the research tasks with our in-house partners.

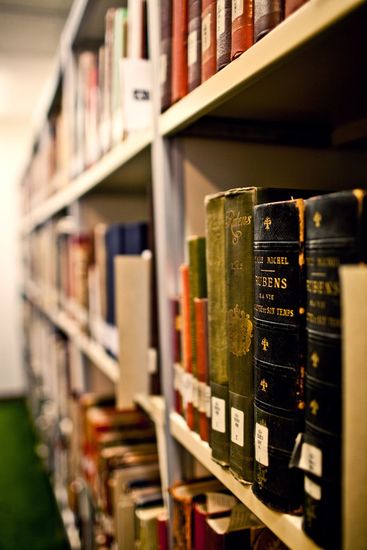

Our primary task as a center of excellence is to offer access to comprehensive, high-quality research collections. The basis, of course, is a reputable library, made thoroughly accessible in the online catalogue of Anet, the network of scientific libraries in Antwerp. As a center of excellence, we are able to add something substantial to this: an extensive collection of visual documentation. We continually monitor new publications and the art market for relevant information on works of art. Since 2012 we have collaborated with the RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History) to make this information available online.

We carry out research and manage our advisory services together with our in-house partners: the Centrum Rubenianum and, since 2012, the Rubens Project of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp. The Centrum Rubenianum publishes the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, while those collaborating on the Rubens Project devote themselves to the technical and historical examination of the Rubens paintings in their collection. To complement the research on Rubens, the Rubenianum has traditionally dedicated itself as well to the broader field of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Flemish art, especially that of Van Dyck and Jordaens. As regards the research carried out here, what I find particularly enriching is the interaction between established senior scholars, who have long been associated with this institution, and new generations of researchers.

In addition to publishing the prestigious Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, what does the institution do to facilitate or stimulate research?

In the first place, we facilitate research by constantly improving access (both physical and virtual) to our collections and by providing a reading-room service. We recently decided to go a step further by encouraging visiting scholars to come to our institution for longer or shorter periods of research, during which they enjoy the privilege of enhanced working facilities. Together with a number of Flemish partners, we are also planning summer courses on Flemish art history, which will take place for the first time in 2015. We regularly hold our own colloquia and also host scholarly activities organized by other national and international institutions. It is part of our role as a center of excellence to bring together scholars and stimulate the exchange of ideas and expertise among researchers and museum professionals. Antwerp – in particular the Rubenianum – is obviously an outstanding meeting place for those studying the art of the Southern Netherlands.

The Rubenianum, like the RKD in The Hague, is an institution that plays a supporting role. How do you engage with researchers at museums and universities?

A characteristic of an institution like ours is our support of and/or interaction with all the universities and museums that give courses in, or possess collections of, old Flemish art, while also maintaining ties to collectors and the art market. So we stand at a crossroads, as it were, acting as a versatile facilitator of expertise by making the information at our disposal accessible to everyone. And, like the RKD, we take a comprehensive view of our field, striving for completeness in documenting the art produced in Flanders in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This means that we must go beyond the collection-oriented approach commonly adopted by museums. Curators and exhibition organizers can make use of our extensive research library, which often contains unique information on paintings that are otherwise hard to trace. With regard to our profile as an institution, the difference between us and the RKD is our clearly delimited scope. If you’re working specifically in the field of Flemish Renaissance or Baroque art, then the Rubenianum is an obvious place to start.

My impression is that, in the past, museum professionals had more time to carry out research on location, whereas now they increasingly expect information and support to be available remotely. We, of course, must keep up with these trends and accommodate their needs.

As far as universities are concerned, students of art history have traditionally been important users of our resources. For a long time we have been offering them introductory sessions and tours of the institution. More recently, we have had great success with students to whom we offer internships and other kinds of work experience. We have come to cooperate with our academic partners in wide-ranging ways, while placing the emphasis on project-oriented collaboration. But there are additional opportunities for structural collaboration that are definitely worth exploring.

The Rubenianum and the RKD recently began to collaborate on enhancing digital access to their collections. Does this have advantages for both institutions?

I’m particularly happy about this intensive and enduring collaboration. Despite the difference in size between our institutions, our tasks are pretty much the same. We’re both active in the field of early-modern art of the Southern Netherlands: this is the sole focus of the Rubenianum, but it has traditionally been a core area of the RKD as well. So it stands to reason that we would seek to join forces. The benefit to a small institution like the Rubenianum is plain to see. For more than fifteen years, RKDimages has been a point of reference that we are happy to reinforce through our collaboration. This allows us to model one of our core tasks on the sound working procedures and high standards maintained by our colleagues in The Hague. Conversely, RKDimages can profit from the knowledge we supply from the perspective of our specialism: Southern Netherlandish painting and drawing. The collaboration offers us ample opportunity to safeguard our own visibility and identity. For example, in the Rubenianum’s forthcoming search interface we will be able to provide more in-depth information, such as Burchard notes or digitized Corpus entries, to specialists researching Rubens and his art.

What does a network like CODART mean to an institution such as the Rubenianum?

As a center of excellence we provide a service to everyone engaged in high-level research into Flemish art, including, of course, professionals employed by museums. It is to our advantage that this important group is so opportunely united within CODART. The value of this network is increased, moreover, by CODART’s efforts to stimulate the active involvement of its members through its events and notification service. It is important that centers of excellence such as ours can become members, because CODART provides us with a valuable platform for publicizing our services, collections and initiatives, and for discovering what museum professionals need and what they expect of our institutions. In recent years I’ve been happy to see CODART’s increasing involvement with the Rubenianum, and I look forward to expanding our fruitful collaboration.

What objectives would you like to see realized in the next five years?

We have recently formulated ambitious plans for the period 2014-18. In general, I expect that the dynamism generated by the Rubenianum Fund since 2010 through its support of the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard will only increase, given the plans to accelerate the pace of publication. In addition, the Antwerp city government decided earlier this year to promote Antwerp in the coming five years as the pre-eminent center of excellence for Rubens research.

I’ve already mentioned a number of concrete goals, such as attracting visiting scholars and holding colloquia and summer courses. With regard to our core task – documenting works of art – it is clear that we will make the most of our partnership with the RKD. We also plan to accelerate the inventorying and conservation of the private working archives bequeathed to us by eminent art historians, in order to increase their accessibility for research. Another explicit goal is to implement collaboration, in the first place with the “Rubens partners” on our premises, as well as with closely allied institutions both at home and abroad.

What are your long-term goals?

That perspective, too, involves the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, the flagship of our institution, which is scheduled for completion in 2020. In the coming years we and our stakeholders must reflect on new avenues of research that could enrich this catalogue or even provide it with a sequel. We have no concrete prospects as yet, but nothing can prevent us from reflecting on our quarters on the Kolveniershof and how they could be better adapted to the needs of the collections, the public and the staff.

In fact, in the here and now we are usually more involved with the long term than we realize: investing in expertise and research is, after all, the most enduring basis for the future understanding of, and interest in, the artistic heritage to which we are all devoted. By administering solid art-historical resources and stimulating the exchange of knowledge, we can strengthen the basis for new research projects, which in turn will give rise to new publications and exhibitions, and thus, most importantly, allow us to reach new audiences.

Véronique Van de Kerckhof is Director at the Rubenianum in Antwerp, Belgium. She has been a member of CODART since 2002.

Suzanne Laemers is Curator of Fifteenth and Sixteenth Century Netherlandish Painting at the RKD (Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie) in The Hague, The Netherlands. She has been a member of CODART since 2007.