Eager to broaden my horizons after finishing school in Sweden, I entered Barnard College in New York in 1978, planning to major in English literature. My studies took a different turn when, through classes in the joint Barnard/Columbia University Art History Department – especially those given by Anne Lowenthal – I discovered the Old Masters. In 1982 I received a Bachelor of Arts degree, and after a year back in Sweden studying medieval English literature at Uppsala University, I decided to return to New York to continue my studies in art history at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. Since then my interests have mainly focused on the art of the Late Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque in Northern Europe.

The Institute had a stellar art history faculty that included Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann, Jonathan Brown, and Colin Eisler, who became my dissertation advisor. The Institute’s location near The Metropolitan Museum of Art meant that our professors frequently taught from the museum’s collection and encouraged the first-hand study of art objects fundamental to all curatorial work. The Institute also had a Conservation Center, where members of the Met’s conservation staff participated in teaching art history students about the materials and techniques of art. Most memorable are classes taught by John Brealey, then Head of Conservation, in the museum galleries. When I received a Master of Arts degree in 1985 – with a major in Northern Renaissance and Baroque Art, and minors in Italian Renaissance Art and the History of Materials and Techniques – Professor Begemann suggested that I begin a student internship with Maryan Ainsworth in the Met’s Paintings Conservation Department. Dr. Ainsworth’s pioneering project, using infrared reflectography to study underdrawings in the museum’s Early Netherlandish paintings, opened my eyes to the possibilities of Technical Art History. It awakened my interest in studying artist’s working processes, and made me aware of the drawing medium as such. I then embarked on a Ph.D. dissertation devoted to the little studied subject of late medieval wall painting in the Southern Netherlands. A Theodore Rousseau Fellowship allowed me to travel to Belgium in 1989, where I spent a year in the photo archives of KIK/IRPA in Brussels and traveled across the country to study and document wall paintings. In 2000 I received a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the Institute. The thesis was later revised and published as a book by Brepols. Following my return to Sweden in 2001, I joined the Research Department of the Nationalmuseum as a translator and researcher, and later as a post-doc fellow, a five-year appointment funded by the Swedish National Bank and the Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities.

The Nationalmuseum is the foremost Swedish collection of pre-1900s European paintings. There are about 800 Netherlandish, Dutch, and Flemish paintings from the fifteenth through the seventeenth centuries – works by Rubens, Van Dyck, Jordaens, and Rembrandt, as well as a broad range of portraits, history, landscape, and genre pieces. Added to this is a renowned graphics collection that includes some 1000 Netherlandish, Dutch, and Flemish drawings. The core of these collections derives from three centuries of royal collecting. King Gustav Vasa (r. 1523-60) began acquiring works by German and Netherlandish artists around 1530. During the Thirty Years’ War, Sweden’s period of military and political ascendancy, the collections were then substantially augmented by war booty. In 1648, for example, a large number of artworks were seized from Emperor Rudolf II in Prague and delivered to Queen Christina (r. 1644-54). In the mid-eighteenth century the royal family acquired the superb art collection of Count Carl Gustaf Tessin (1695-1770), largely assembled while he served as Swedish ambassador in Paris 1739-42. Among its riches are a large number of drawings purchased at the 1741 estate sale of French financier Pierre Crozat, including over 500 Netherlandish, Dutch and Flemish drawings. Art from other privately held collections – including those of Dutch and Flemish industrialists who had settled in Sweden in the seventeenth century – were incorporated with the royal collections when, in the 1780s, King Gustav III (r. 1771-92) set about creating a specially designed art gallery in the Royal Palace in Stockholm. The Royal Museum, founded in the king’s memory in 1792, was one of Europe’s first public museums. The collections later went on display in the new Nationalmuseum, which opened in 1866.

The best way to gain a thorough knowledge of the totality of a museum’s holdings may be through working on scholarly collection catalogues. During my years as a researcher at the Nationalmuseum, I became involved in two major cataloguing projects financed by The Getty Foundation and the Swedish Royal Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities. One involved the museum’s Flemish paintings before 1700, the other the Netherlandish, Dutch, and Flemish drawings in Swedish Public Collections. The first project entailed studying the paintings using dendrochronology, x-radiography, and infrared reflectography. My longstanding interest in artists’ materials and working processes proved invaluable when I was charged with coordinating the technical examinations carried out in collaboration with members of the museum’s Conservation Department and visiting scientists. The paintings catalogue, with comprehensive entries and technical notes, was co-authored with Görel Cavalli-Björkman and published in 2010. In 2018 Börje Magnusson, hired to catalogue the Dutch drawings, published his contribution in the museum’s series on Old Master drawings initiated by Per Bjurström in 1972. Within the next few years I hope to finish my own volume on the sixteenth-century Netherlandish and seventeenth-century Flemish drawings, temporarily put aside when, in 2011, I was appointed Curator of Paintings, Drawings and Prints before 1700 in the Department of Collections.

My new position proved to be both demanding and rewarding, as we immediately had to plan for the evacuation of the collections before closing the museum in 2013 for a major renovation campaign. The creative and challenging activity of rearranging exhibition spaces and rethinking displays is truly a team effort. The close collaboration with other staff members – curators, conservators, educators, scenographers, and technicians – over the next five years was a thoroughly enjoyable experience. By the reopening in 2018 we had completed new hangings in all the Renaissance and Baroque rooms. Early on the decision was made to depart from a traditional arrangement by schools, and instead combine works from the Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, to underline the cross-fertilization that results from the flow of artists, artworks, and ideas across Europe. Visitors to the Baroque galleries, for example, can now view works by Rembrandt next to those by Caravaggists of various nationalities active in Rome and Naples in the first decades of the seventeenth century. Another major change involves the decision to mix different object categories – paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts – throughout the displays. In the more intimate spaces of the cabinets thematic hangings were introduced, on subjects ranging from ‘art for private devotion’ to ‘scenes of everyday life,’ with changing displays of drawings, prints, and illuminated manuscripts. Showcases for smaller-sized paintings and sculptures enable visitors to view works from close-up.

-

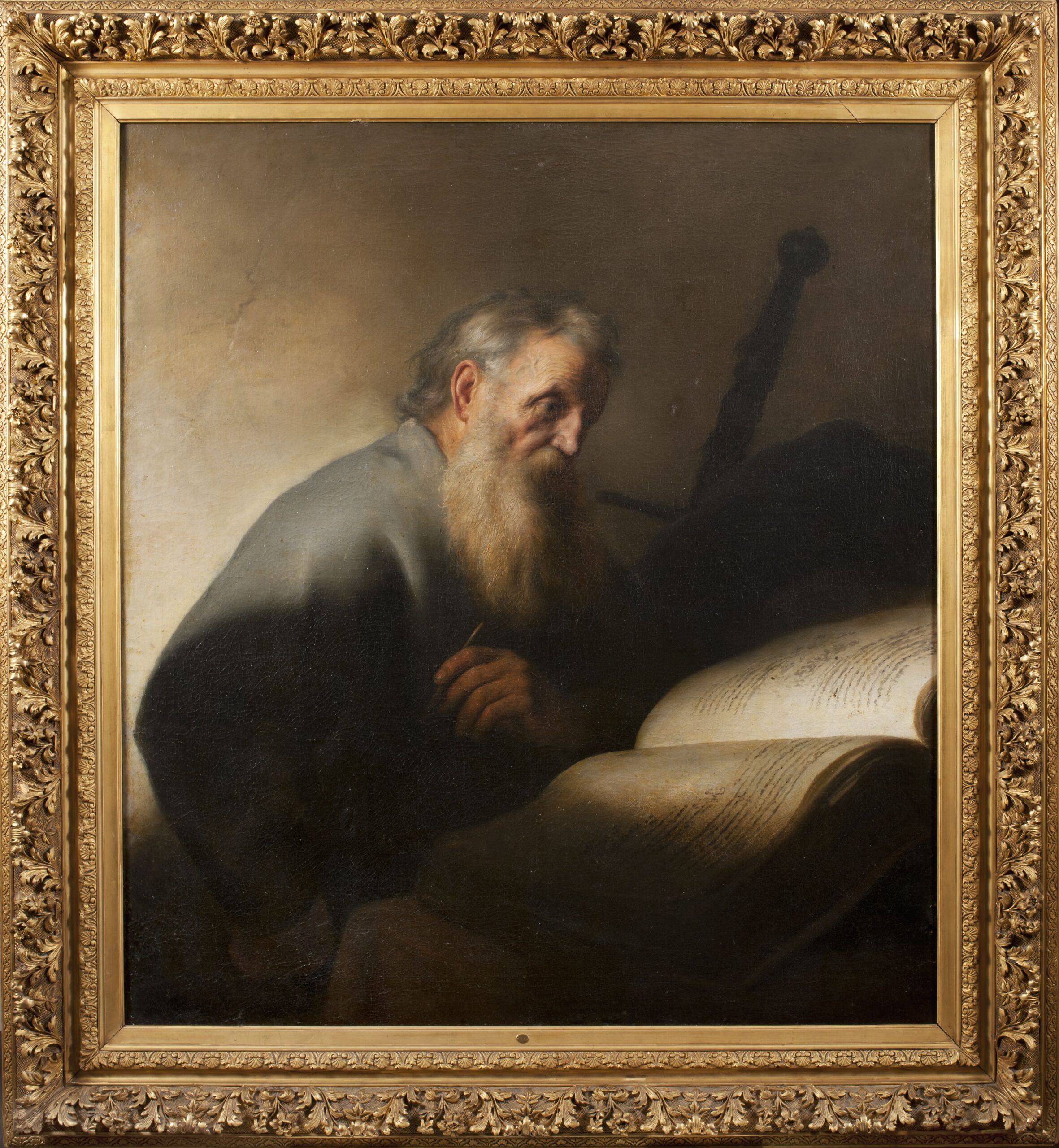

Jan Lievens (1607-1674), The Apostle Paul, ca. 1627-1629

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

- Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert (1613/1614-1654), Study of a Boy’s Head, ca. 1644-1645 Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

With such a quality collection of Northern European sixteenth– and seventeenth-century art, it can be a challenge to expand this area of the collection. Funding provided by a generous donor allowed us to augment the paintings collection with Jan Lievens’ poignant Apostle Paul at His Writing Desk, which exemplifies the artist’s close connection with Rembrandt in the late 1620s. This painting, acquired in 2012, has an early Swedish provenance from the collection of Count Gustaf Adolf Sparre (1746-94). There followed the acquisition at TEFAF in 2015 of Thomas Willeboirts Bosschaert’s charming Head of a Boy, a study for the museum’s suave Amor Triumphant Amongst the Emblems of Art, Science, and War of c. 1644/45. In 2016 we were able to purchase Isaack Luttichuys’ fine Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Pair of Gloves (1661) at a sale in Stockholm. More recently, we acquired a beautifully preserved Flower Garland with a Standing Virgin and Child of c. 1645-50 by Gerard Seghers and Erasmus II Quellinus. Among the drawings purchased at the important sale of I.Q. van Regteren Altena’s collection in 2014-15 are two impressive nature studies: A Male Lumpsucker of the 1590s by an artist from the circle of Hendrick Goltzius; and A Sticky Nightshade of 1683 by Herman Saftleven.

A deeply rewarding task of the curator is the planning of exhibitions, large and small, for which our own collections often serve as the starting point. Collaboration with other departments of the Nationalmuseum as well as with other museums internationally is always a goal. In 2009 we were approached by Friso Lammertse of the Museum Boijmans-Van Beuningen with a proposition to jointly undertake an in-depth technical study of Anthony van Dyck’s two versions of Saint Jerome with an Angel of c. 1618-21, one of which is owned by the Boijmans, the other by the Nationalmuseum. The results were presented in a focus exhibition on the artist’s early work and use of replicas, shown in Rotterdam and Stockholm in 2010. Another favorite exhibition is one produced in 2017, working with our colleagues from the Louvre to present a broad overview of Count Tessin’s rich collection of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and decorative arts. A different version of this exhibition was organized in collaboration with The Morgan Library and Museum and shown in New York the following year. This offered the American public a view of Tessin’s important eighteenth-century French paintings, together with broad selection of Old Master drawings. Currently we are once again working with our French colleagues on a dream project, this time an exhibition of Giorgio Vasari’s drawings collection, focusing on the role of the Libro de’ Disegni as the visual complement to his famous Vite. For this event, scheduled to take place in 2022, we will be reuniting for the first time those parts of Vasari’s vast drawings collection housed in the Nationalmuseum and the Louvre. For me personally this project is a way of honoring the legacy of my great predecessor Per Bjurström, and of Oswald Sirén, pioneering Swedish scholar of the Renaissance.

Recently I was happy to see that Judith Leyster’s sensitive rendering of a Boy Playing the Flute had been selected for inclusion in the CODART Canon! This is one of my personal favorites, and I will have the pleasure of writing about it for the HerStory blog. Since becoming a member of CODART in 2003, I have attended most of the annual conferences held in various European cities. Over the years membership has led not only to invaluable professional contacts but also lasting friendships. It is an honor to be able to welcome the members to the Nationalmuseum for the CODART 23 Congress from 30 May until 1 June 2021.

Carina Fryklund is Curator of Old Master Paintings, Drawings and Prints before 1700 at the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, Sweden. She has been a member of CODART since 2003.

In 2013, she wrote an article about the Dutch and Flemish collection at the Nationalmuseum for the CODART eZine, find it here. She has also published articles on the acquisitions mentioned above, all available (Open Access) through the following links: A Male Lumpsucker (here), Saftleven’s A Sticky Nightshade (here), Willeboirts Bosschaert’s Study of a Boy’s Head (here) and Luttichuys’s Portrait of a Young Man Holding Gloves (here).