The long path to curatorial work at the Rembrandt House Museum began for me with drawing. Schoolboy sketches and cartoons led to drawing lessons, which in turn led to study of studio art at the University of Guelph. I was joined by my twin brother Lloyd DeWitt, who like me quickly became fascinated with art history, and specifically Rembrandt and his pupils. It was with the aim of doing original research on an artist in Rembrandt’s circle that I proceeded to Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, for a Master’s. My thesis addressed iconography, biography, connoisseurship and social context, and could even incorporate technical research, owing to the expertise in the Art Conservation program at Queen’s, including infrared reflectography. The subsequent dissertation under Volker Manuth involved extensive study of objects and questions of attribution, but also iconographic and archival research. This prepared me quite directly for the newly-formed position of Bader Curator of European Art at the Agnes Etherington, which I could start in 2001. My main task was to research and catalogue more than 270 paintings that Alfred, Helen and Isabel Bader had donated, or would donate to the museum, to form the Bader Collection. They included many challenges of attribution and interpretation. A highlight of this position was joining the Baders at sales to make new acquisitions. I also organized exhibitions drawn from the permanent collection, and occasionally also loan exhibitions.

With my step to the Rembrandt House Museum in 2014, loan exhibitions took center stage. Here I have been working with a team of experienced and highly motivated colleagues, drawing on the network developed through research and further facilitated in large part by CODART. This remarkable museum, based on the house in which Rembrandt lived and worked for nineteen years, is devoted to telling the story of Rembrandt’s life, work, and his reception over the ensuing centuries. Over its first decades of existence the Rembrandt House focused on the etchings, building and displaying a representative collection, having been established at the tail end of the Etching Revival. It includes multiple states of The Three Crosses, and a superb early impression of the Hundred Guilder Print. One of my favorites is the famous Self-Portrait with Saskia of 1634, which projects an important role for Rembrandt’s new partner in managing their joint art enterprise. It was printed endlessly, underscoring the importance of Saskia’s role in Rembrandt’s art, which remains underestimated.

In recent decades, however, with the historically oriented reconstruction and installation of the house, it became an important “object” in the collection. One of my tasks has been to research the Kunstcaemer, working with talented interns to review the suitability of the objects displayed in it, as well as their provenance with respect to questions of looting and slavery, and lacunae, such as the bust of an African listed in Rembrandt’s inventory.

-

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Self-Portrait with Saskia, 1636

Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam

-

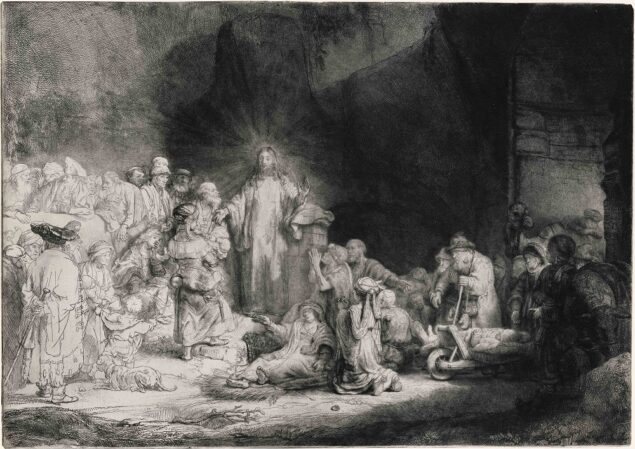

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Christ Preaching (‘The Hundred Guilder Print’), ca. 1648

Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam

By this time, the museum’s purview had already expanded to embrace paintings and drawings. The first major project to which I contributed was Rembrandt’s Late Pupils (2015), followed by ones on nude model studies (2016), on Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck (2017), Rembrandt’s Social Network (2019), the depiction of Blacks in the art of Rembrandt and his time (2020), and two on the Etching Revival (2018, 2022). For the Rembrandt Year 2019 I was also asked (together with Franziska Gottwald) to contribute an essay for the publication for the exhibition Rembrandt’s Light at Dulwich Picture Gallery.

Most recently, in conjunction with our major exhibition on Samuel van Hoogstraten (2025), my colleague Leonore van Sloten and I worked not only on our own presentation, but also with a large team of scholars on a catalogue raisonné of the artist’s paintings, drawings, and prints. We could both contribute more extensive essays to the publication of our wonderful partner museum, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Currently I am working on an exhibition project tentatively entitled Turbans, Carpets, and Rembrandt, on the impact of Southeast Asia, and more specifically the Ottoman and Persian empires, on the art of Rembrandt and his time, in which we will look closely at Rembrandt’s contact points with these cultural spheres, and his artistic responses to them.

The opportunity to carry out research and present the results to various audiences, including the wider public of art lovers, is for me the most compelling aspect of curatorial work at the Rembrandt House Museum. One highlight has been the acquisition of a painting by the late Rembrandt pupil Abraham van Dijck for the museum’s permanent collection: The Old Painter. In my research on the artist for a monograph, an external project supported at the time directly by Bader Philanthropies, this painting formed part of the evidence that Van Dijck had paid a visit to his former teacher around 1656. He studied the further development of Rembrandt’s late style, in a deeply resonant way, picking up on its meditative potential. Besides the insight that the artist was here reflecting on the idea of Vita brevis, ars longa, how the artist could conquer death through lasting fame, the acquisition and cleaning by Lidwien Wösten revealed a painter’s joke, with the tip of the brush just touching the edge of the panel. The compositional lesson in creating tension with contact points at the edge came of course from Rembrandt. Our multitalented colleague Iris Kost knew just how to handle the tricky framing challenge.

Philips Koninck (1619-1688), River Landscape, 1676. Oil on canvas, 92,5 x 112 cm

Rembrandt House Museum, on loan from the Rijksmuseum

There arose a strong wish at the museum to bring my research activity, until then conducted on a freelance basis outside of museum hours, fully into my role at the museum. Bader Philanthropies has now stepped in to make this possible, with a major grant to support the formation of the Alfred Bader Research Center at the Rembrandt House Museum. It consists of my curatorial position, a two-year fellowship, and secure funding for the Kroniek. This is a natural step forward from their generous support of the Samuel van Hoogstraten Catalogue Raisonné project in collaboration with the RKD, and previously a project to translate, edit and publish the last two remaining volumes of Werner Sumowski’s Drawings of the Rembrandt School, to be published by Brill. I will right away embark on a monographic study on Philips Koninck, and investigate the work of Karel van der Pluym, in both cases emphasizing the analysis of their painted oeuvres. At the same time, our first Bader Fellow, Jochem van Eijsden, has already been making rapid progress in researching the life and work of Barend Fabritius, including some exciting new attributions to this neglected Rembrandt pupil, drawing him out of the shadow of his famous older brother.

By researching these important artists who worked directly with Rembrandt over the course of his storied career, we can not only draw the line more clearly between his works and those of his closest and best-trained imitators, but we follow his activity as a teacher and colleague, and trace the issues, techniques and theoretical interests that occupied him at various points in time. Moreover, many of these pupils also spent time in his house, now the Rembrandt House Museum, and thereby earned a place in this venerated space.

David de Witt is Senior Curator at Museum Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam. He has been a member of CODART since 2001.