At Drottningholm in Sweden there is a unique collection of sculptures by one of the most celebrated sculptors of the early Baroque, Adriaen de Vries (c. 1556–1626). De Vries, son of an apothecary, originated from The Hague (he signed his works “Adrianus Fries Hagiensis Batavus Fecit”) but he was active as a sculptor at several courts and in cultural centers in Italy and Central Europe during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. He probably started his career as an apprentice to a goldsmith in Delft, after which he spent several years in Giambologna’s large workshop in Florence, one of Europe’s most advanced sculpture studios. Like many other fiamminghi, De Vries stayed in Italy for a long time. His expertise in modeling and his technical skills appealed to Europe’s art patrons, who were eager to obtain bronze sculptures – in sizes ranging from small to monumental – to adorn their Kunstkammern, galleries, and gardens. In 1689 De Vries was commissioned by Rudolf II, in Prague, to execute Psyche Carried by Cupids (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm) and Mercury and Psyche (Louvre). There followed a few nomadic years between The Hague, Augsburg, and Italy, before De Vries eventually became court sculptor to Rudolf II.

-

Adriaen de Vries (ca. 1556-1626), Psyche Carried by Cupids, 1590-1592

Photo: Hans Thorwid, Nationalmuseum

-

Adriaen de Vries (ca. 1556-1626), Neptune, 1617

Photo: Magnus Persson, Nationalmuseum

The fact that most of the De Vries sculptures ended up in Sweden can be explained by the country’s success in the Thirty Years’ War in the seventeenth century. Swedish forces laid siege to Prague towards the end of the war in July 1648, and the spoils of war they seized included the De Vries sculptures from the collections of Rudolf II and Albrecht Wallenstein. The latter had adorned his palace garden in Prague with sculptures by De Vries (eventually replaced with copies made in 1900-1913 by the foundry of Herman Bergman in Sweden). Just over ten years later, Frederiksborg Castle in Denmark was pillaged as a consequence of the Northern Wars. The Neptune Fountain, commissioned by Christian IV from De Vries as an allegorical tribute to himself and to Denmark as the ruler of the Baltic Sea, had been placed in the outer courtyard in c. 1620. In 1659 it was dismantled and removed by the Swedes to signify that the Danes were no longer masters of the Baltic Sea.

It is not known exactly where the sculptures from Prague were taken upon arrival in Sweden. Some were stored at Ulriksdal and Gripsholm. Neptune was installed at Drottningholm at an early stage. However, it can hardly have been the intention to keep it in its original format given its symbolic connotations. The Dowager Queen Hedvig Eleonora, who bought the palace in 1661, had quickly embarked on a plan to transform the garden into a formal baroque garden. It was the architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger (1654-1728) who added sculptures to it in the 1680s. He installed some of the De Vries statues on pedestals at the corners of the parterre de broderie to emphasize the symmetry of the garden.

Adriaen de Vries (ca. 1556–1626), Hercules Fountain

Drottningholm Palace, Photo: Per-Åke Persson/Alexis Daflos, Nationalmuseum

Tessin also created a free fountain composition Hercules fountain, modelled on the De Vries fountain in Augsburg that he had seen on his travels. Tessin placed Hercules Fighting a Dragon (originally from Prague, probably in Rudolf II’s collections) on top of the fountain with several smaller sculptures on and around the plinth, including the naiads and tritons from the Neptune Fountain – in other words, a mixture of sculptures from Prague and Frederiksborg. The original iconography was transformed and Kristian IV’s monogram on the head of the lion groups was removed. Neptune himself from the Danish fountain was placed at the seaside, where it still stands.

Adriaen de Vries remained in Prague after the death of Rudolf II (1612) until his own death in 1626. He executed commissions for princes in Prague and the Germanic territories, but none for clients in his native country, the Netherlands. De Vries had no direct successors, probably because of the Thirty Years’ War. But by the second half of the seventeenth century, every prince or ruler wanted large bronze sculptures in their garden, especially since there was a lack of marble in the north. At the end of the Swedish Era of Great Power, by 1718, there were around thirty bronze sculptures, most of them by Adriaen de Vries, in Drottningholm. Sweden was a sculpture-poor country at this time, and this variety of high-quality bronze sculptures was a major attraction.

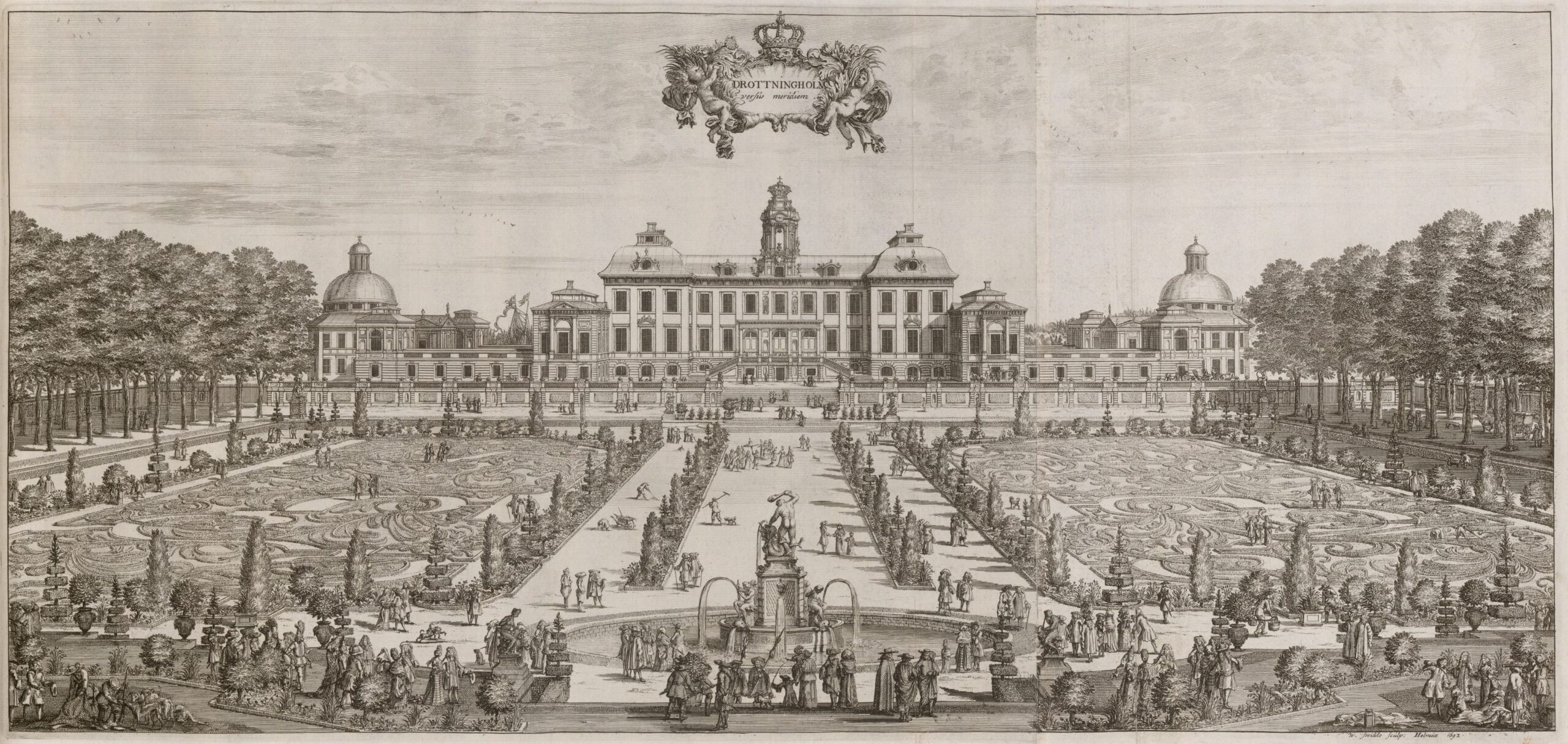

Drottningholm versus meridiem, from Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, Erik Dahlbergh (1625-1703), Willem Swidde (1660-1697) Sculpsit

Photo: Kungliga Biblioteket/Royal Library, Sweden

With few exceptions, the sculptures remained in place until modern times. Once it became clear how much damage they had suffered from exposure to the elements, they were replaced by new bronze casts from the 1990s onward. In 2001, a new museum was opened in the old Dragoon Stables, a building from c. 1815 at Drottningholm Palace, where the originals were placed on display. The museum is a partnership between the Royal Court, the Nationalmuseum, and the National Property Board in Sweden (Statens Fastighetsverk). The display was planned by Magnus Olausson, Director of Collections at Nationalmuseum and designed by Henrik Widenheim and Rebecka Forssberg. The landscaping is somewhat reminiscent of Tessin’s formal garden, with plinths made of sandstone from Gotland. Above all, the exhibition focuses on the artists’ technique, as studied and emphasized at the exhibition Adriaen de Vries 1566-1626: Imperial Sculptor (from 1998-2000, shown in Amsterdam, Stockholm, Los Angeles, and Augsburg with an extensive catalogue edited by Frits Scholten). Technical research was then undertaken by Jane Bassett at the Getty Conservation Institute and Elisabet Tebelius-Murén at the Nationalmuseum to find out more about De Vries’s working methods and the materials he used.

De Vries’s sculptures were cast in one piece, and required only a minimum of chasing and afterwork, testifying to the sculptor’s great skill. He applied direct casting, and part of the core of clay and the armature was never removed from the inside. In the cold and changeable climate of the North, water seeped into the sculptures and marred the core, creating cracks. In the Museum De Vries, visitors can inspect the sculptures at very close range in a way that was not possible before. They can now see the amazing detail work that was originally executed in wax (on the core in clay). Museum de Vries is accessible to the disabled and visually impaired. Labels and texts are in large font and Braille and in some cases relief images. There are also special information posts that clarify De Vries’s technique and the principle of bronze casting with the lost-wax process.

Other sculptures by De Vries are on display at the Nationalmuseum in the permanent exhibition which opened in October 2018. The collections are organized chronologically, and sculptures are exhibited alongside with paintings, textiles and decorative arts from each of the different periods. Psyche Carried by Cupids is the first sculpture encountered by visitors as they enter the permanent exhibition on the top floor. It represents the beautiful Psyche, carried by winged putti to Mount Olympus, the abode of the gods, to be reunited with her beloved Amor. The statue was cast for Rudolf II in 1590–1692 and was the first bronze listed in the emperor’s Kunstkammer. It is one of a pair with Mercury and Psyche, cast in 1593. They were transferred to Sweden in consequence of the Peace of Westphalia (1648), and were listed in the 1652 inventory of Queen Christina’s collection. Psyche carried by Cupids was never installed in Drottningholm, but passed through different collections in Sweden before it was eventually offered to the future Nationalmuseum by the Von Wahrendorff family in 1863. Mercury and Psyche, on the other hand, was given to the French diplomat Abel Servien by Queen Kristina after her abdication in 1654 and eventually ended up in the Louvre.

Renaissance Galleries, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, October 2018

Photo: Anna Danielsson, Nationalmuseum

The De Vries sculptures with Swedish connections also include a Triton on long-term loan to the Rijksmuseum. It is one of three tritons originally from the Neptune Fountain in Frederiksborg and later the Hercules Fountain in Drottningholm, which have since been replaced by copies in the gardens.

Linda Hinners is Curator of Sculpture at the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

The Museum De Vries is open to the public on the annual “Museum De Vries Day.” It is open all year round for guided tours for groups, provided these are booked in advance.