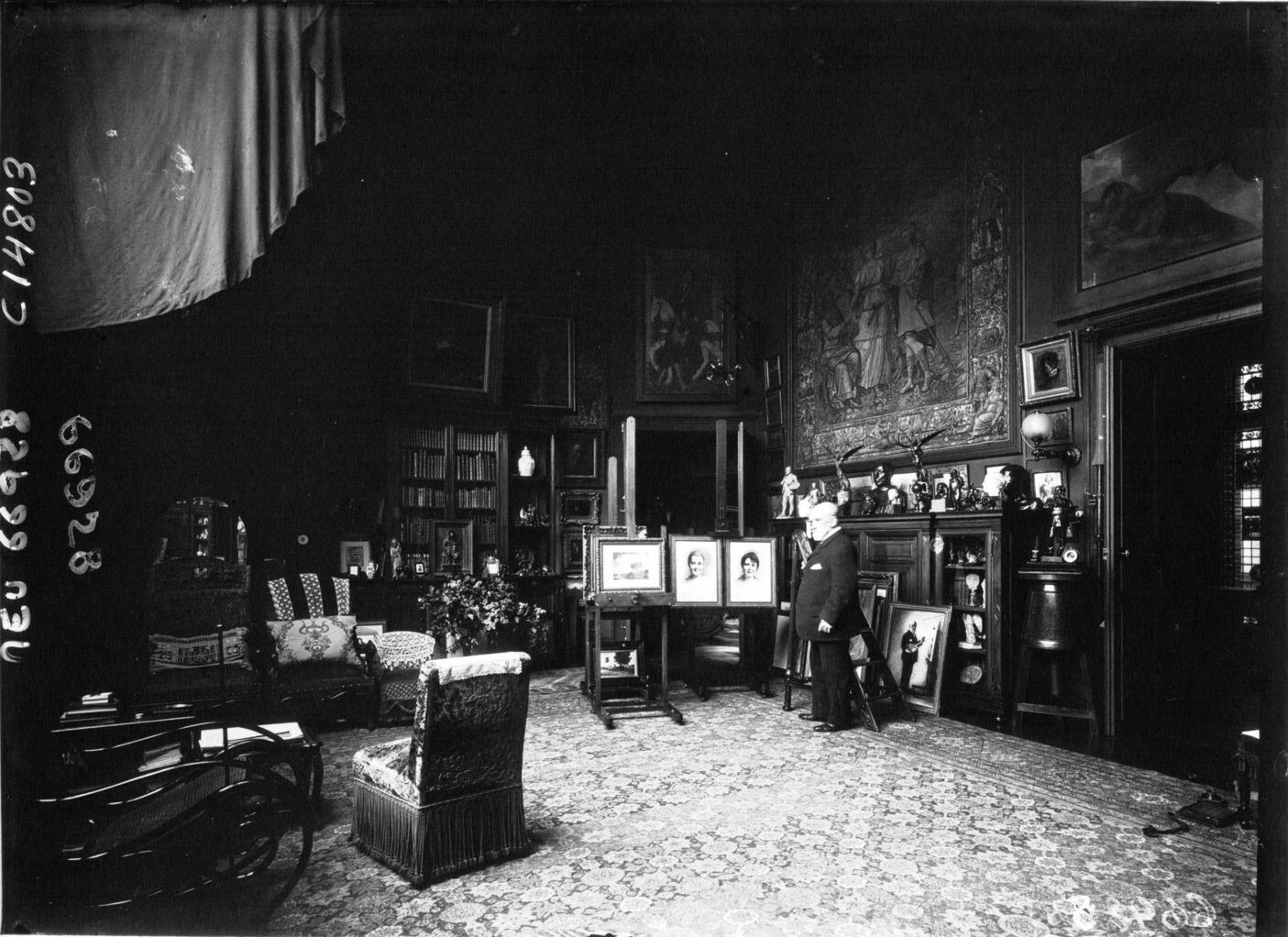

Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) is one of the great French academic portraitists of the late nineteenth century and his importance as a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris – and later as its director – was enormous. An old photograph shows him in his Parisian atelier, where he lived surrounded by his collection (fig. 1). He spent much of his substantial income as a high society portraitist on drawings. His demands were simple: he wanted only the best drawings by the greatest artists since the Trecento.

Bonnat acquired most of his collection between 1880 and 1900. Around the turn of the century, when Old Master drawings gradually increased in price while the market for his portraits was shrinking, he was compelled to stop making new purchases. Bonnat’s home town of Bayonne had given him a scholarship to study in Italy. For that reason, towards the end of his long life, between 1902 and his death in 1922, he donated the bulk of his art collections to the city. The catalogue raisonné of the Netherlandish and German drawings and prints of the Musée Bonnat-Helleu – 220 works in total – will be published this year. The catalogue will conclude with lists of Bonnat’s drawings from Northern Europe that are not in Bayonne but are now in other museums or private collections.

The entries on the Dutch and Flemish works were written by Olivia Savatier, curator for the Dutch and Flemish drawings in the Louvre, and myself. Those on the German drawings and prints were written by the art historian Franck Guillaume, Hélène Grollemund, exhibition manager at the Louvre, and Sophie Harent, director of the Musée National Magnin in Dijon. We are grateful for the sponsorship of the city of Bayonne and the Ratjen Foundation, and we also want to thank David Lachenmann, the two consecutive directors Sophie Harent and Benjamin Couilleaux, and all the staff of the Musée Bonnat-Helleu for their help and enthusiasm in supporting this project.

The Bayonne drawings were already well known during Bonnat’s lifetime, and he was extremely generous in making them available to art lovers. He sent photographs to diverse specialists and lent his drawings to major exhibitions of the day like the Rembrandt exhibition in Leiden in 1906. All this changed after his death. His will contained a clause stating that the drawings could no longer be displayed outside Bayonne. Before he sent them there from Paris, they were added meticulously to the Louvre’s inventory lists and then sent on permanent loan to Bayonne (but without any possibility of the Louvre reclaiming them). Only three exceptions have been made since 1922: a selection of French drawings from the nineteenth century were shown in the Louvre in 1979 and all the drawings by Leonardo da Vinci are currently exhibited there in the show devoted to the Italian master. The third exception was in 1985, when the French culture minister Jack Lang agreed to send two works to Vienna – the famous Head of a Stag by Albrecht Dürer (fig. 2) and Wing of a Blue Roller by Hans Hoffmann – for inclusion in Fritz Koreny’s wonderful exhibition featuring Dürer’s drawings of animals and plants in the Albertina.

In 1992, the Musée Bonnat acquired several new Flemish drawings, with the major donation from the famous Parisian art dealer Jacques Petithory (1929–1992). The most important drawings from northern Europe in his collection date from the latter half of the sixteenth century and are by Flemish artists who were active in Italy, like Hans Speckaert and Lodewijk Toeput (Pozzoserrato). The earliest Netherlandish drawings in Bonnat’s collection are from the fifteenth century. Bonnat bought several of them at Christie’s in London in July 1884, when the auction of the collection of Andrew Fountaine (1676–1753, Narford Hall, Norfolk) was sold by his descendants. The Head of the Virgin, by a follower of Rogier van der Weyden, came from this collection (fig. 3). It illustrates superbly Rogier’s enduring influence, decades after his death in 1464.

- 3. Follower of Rogier van der Weyden, Head of the Virgin, ca. 1480-1490, silverpoint and red chalk, 19.8 x 14.4 cm, inv. 214

- 4. Bernaert de Rijckere (ca. 1535-1590), Head of a Man, ca. 1560, red and black chalk, 15 x 13.7 cm, inv. 1493

The sixteenth century is represented only by a small group of Netherlandish drawings, such as one by Pieter Cornelisz. Kunst. Bonnat had no luck with his little group of drawings then attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Elder, as all five are now regarded as copies made in the late sixteenth century. In the Gigoux sale (1882) he paid a large sum to purchase a very impressive Head of a Man by Bernaert de Rijckere (c.1535–1590) that came from the prestigious collection of the Amsterdam dealer Jan Pietersz. Zomer (1641–1724) (fig. 4). The drawing was sold as by an anonymous Dutch artist and is attributed here to Rijckere for the first time.

5. Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Death of Hippolytus, ca. 1610, pen and brown wash, 22 x 32.1 cm, inv. 1441

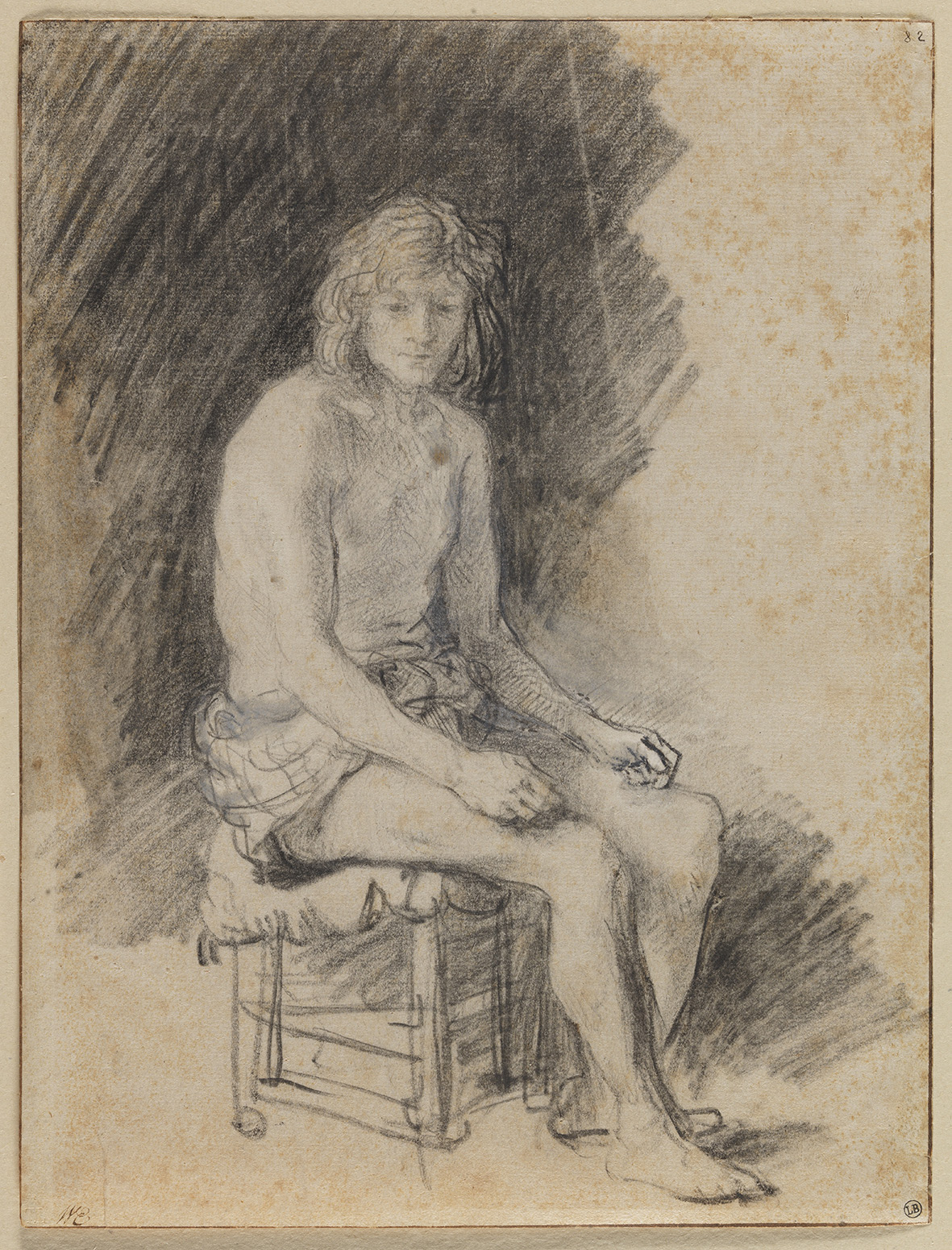

Léon Bonnat focused on the Flemish and Dutch drawings of the seventeenth century. Particularly famous today are those he owned by Rubens, Van Dyck, Jordaens, and Teniers. Besides Rubens’s celebrated sheet with studies for the Erection of the Cross, this ensemble includes other important drawings by the master, such as the Death of Hippolytus from c. 1610 (fig. 5). Léon Bonnat was one of the first collectors of his day to appreciate the genius of the spontaneous, rapidly-executed pen-and-wash drawings which Rubens produced in the first few years after returning from Italy. It would not be until the 1920s that this technique won general acclaim. The second group of seventeenth-century drawings from northern Europe on which Bonnat focused his attention consisted of works by Rembrandt and his circle. Bonnat’s collection contained over 120 drawings by the master and his workshop – most of which were given to the Louvre in 1919 – including examples of each of his themes. A Young Man Seated was executed by one of the master’s pupils; the sheet shows many corrections in pen by Rembrandt himself (fig. 6). The young man depicted in this drawing frequently sat for Rembrandt and we find him in other works by the master and his workshop.

- 6. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and an unknown pupil, Young Man Seated, black chalk, brown wash, heightened with white, 25 x 19 cm, inv. 646

- 7. Adriaen van de Velde (1636-1672), Seated Female Nude, ca. 1660-1670, red and black chalk, 26.6 x 21 cm, inv. 160

Adriaen van de Velde’s Seated Female Nude in red and black chalk is a fine example of work by the Dutch masters of the seventeenth century outside Rembrandt’s circle (fig. 7). In addition, eighteen drawings by Van Goyen, Backhuysen, Cornelis Visscher, Cornelis Saftleven, and Adriaen van Ostade in Bayonne illustrate other aspects of the Dutch Golden Age. Van Goyen is represented with two characteristic landscapes and Backhuysen with two seascapes – one of which Bonnat misattributed to Willem van de Velde. The drawing by Visscher is one of his heads of a woman, a study on paper, and there are two compositions with peasants by Van Ostade. One of these, from the collections of Dezallier d’Argenville and Peter Adolf Hall, depicts a group of peasants making music and has been unknown until now. For French collectors of the nineteenth century it would have been unthinkable to have a collection of Dutch drawings without including images of animals. Bonnat thus purchased a beautiful picture of a duck by Cornelis Saftleven from the collection of the great collector Horace His de la Salle, a major donor to the Louvre, to whom the museum is now devoting an exhibition.

8. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), The Three Trees, 1643, etching with drypoint and burin, 21.7 x 28.5 cm, inv. 2567

The handful of prints from the Bonnat collection are virtually unknown today: The Milkmaid by Lucas van Leyden (with a characteristic watermark of a unicorn) probably only entered the collection because Bonnat was unable to acquire a drawing by the master; Bonnat also acquired 19 prints by Rembrandt and several others by or after Rubens and Van Dyck. The Rembrandt etchings came from leading English collections and Bonnat probably acquired them through Colnaghi. It was a great surprise to see that they had been completely overlooked until now. The Three Trees by Rembrandt came from the collections of John Sheepshanks (1787–1863), Joseph Maberly (1783–1860) and John Griffiths (1806–1885); the Portrait of Ephraim Bonus originated from the collections of Edward Astley (1729–1802) and Charles Rogers (1711–1784), and the Hundred Guilder Print from Pierre Rémy (1715–1797). The quality of the impressions is very high and Frits Lugt even mentioned some of them in his first volume on the Marques de Collection (“Collector’s Marks,” 1921). One of these was Rembrandt’s Three Trees, an etching that Bonnat held in high esteem (fig. 8): The view of his atelier shows us the engraving displayed on an easel in the middle of the room (fig. 1).

David Mandrella is a professor at IESA Arts & Culture – International studies in history and business of art & culture.