These days, political satire is blossoming.

No matter where you fall on the political spectrum or how you feel about the current administration in any number of countries around the world, every week there is an abundance of new satirical imagery to enjoy. There are editorial cartoons in newspapers, pundits and sketch comedies on television, and memes and other content on the internet. Unless a person disconnects from all forms of media, there is no escaping it. And while the overwhelming quantity and the digital delivery of this imagery are new, the practice of using pictures to comment on political leaders and events has important and underappreciated precedents in early modern Dutch print culture.

Jan Saenredam (1565-1607), Allegory of the Flourishing State of the United Provinces, 1602

Krannert Art Museum (inv. no. 2018-9-1)

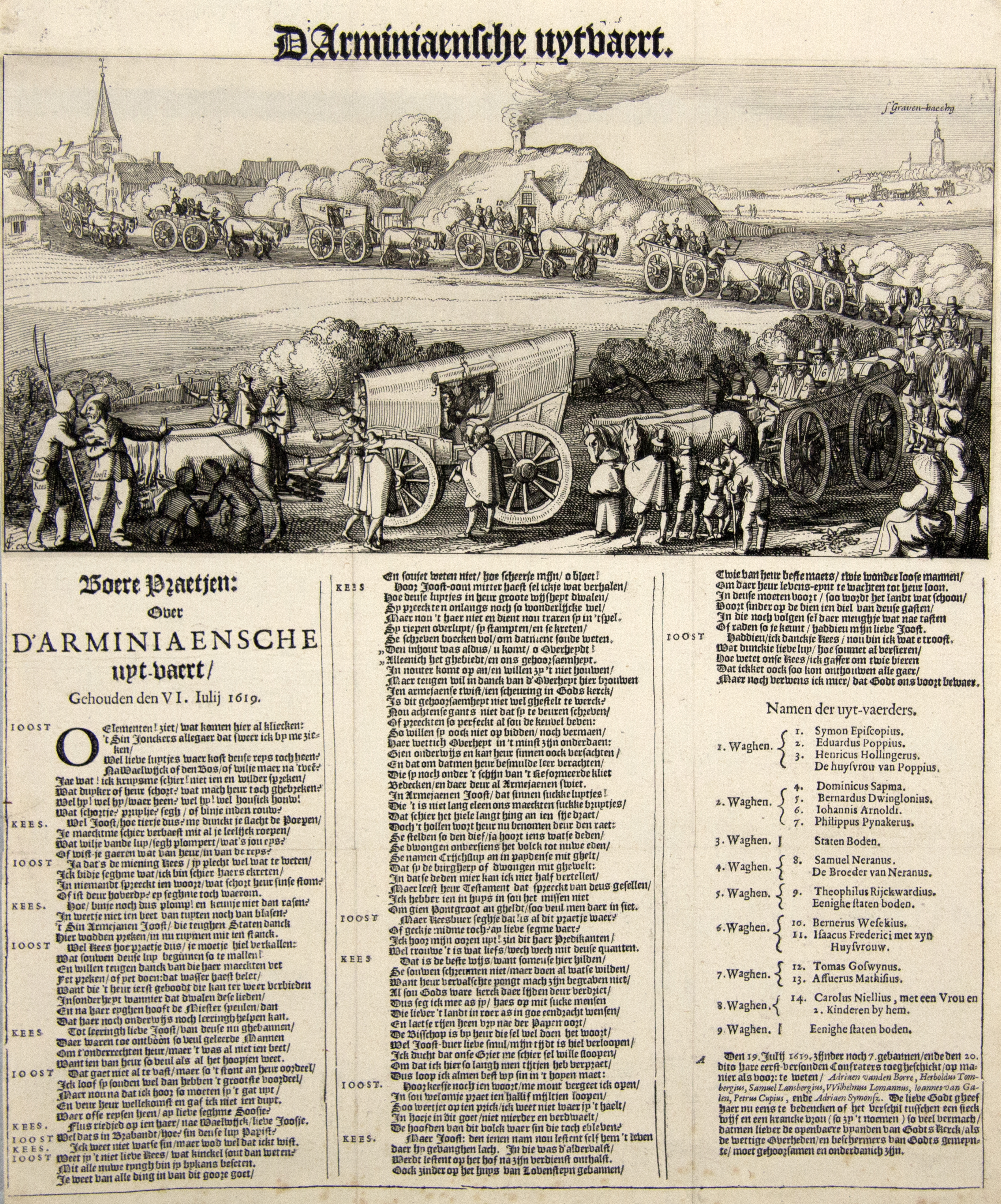

Thanks to several recent and substantial purchases, Krannert Art Museum, located at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has amassed one of the best collections of early modern Dutch political prints in North America. But what exactly constitutes a political print? The category is clearly subjective. Defined broadly, it is any printed image of an event or person related to the state or government. They can be allegories, satires, cartoon strips, portraits, maps, or so-called “news prints,” which claim to be truthful illustrations of recent events. This category includes single sheet ‘fine art’ prints, such as finely wrought portraits of European leaders, which connoisseurs and museums have long cherished. But it also includes prints of lesser standing, such as illustrated pamphlets and broadsides. These text-heavy publications are often found in libraries and archives, and some collectors and collections have been hesitant to consider them to be ‘art.’ Another type of print that is sometimes valued more for the information it contains or its historical significance rather than its artistic value is maps. However, like pamphlets and broadsides, maps were sometimes made by noteworthy printmakers and could incorporate highly innovative decorative components, and even cruder works can tell us something about visual media and politics in early modern Europe.

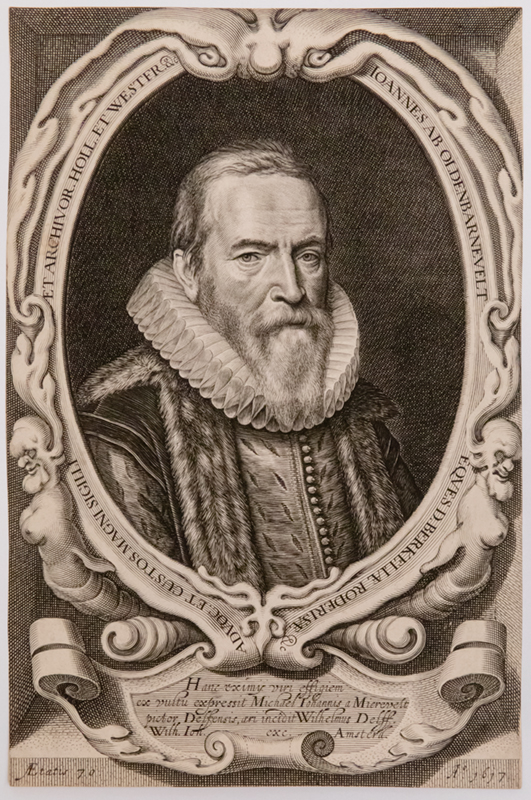

Willem Jacobsz. Delff (1580-1638) after Michiel van Mierevelt (1566-1641), Portrait of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, 1617

Krannert Art Museum (inv. no. 2019-13-1)

What did Dutch political prints mean for early modern audiences? Who made them? Who bought them? Why? Were they meant to spur public debate and discussion or were they more partisan, made to incite or uplift a particular group? These are some of the questions I pondered while I was writing my PhD thesis on depictions from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of the executed Dutch statesman Johan van Oldenbarnevelt (1547–1619). While my research focused on images of this one man, I discovered that art historians often neglected the sorts of prints I needed to research as comparative material, even when well-known printmakers were involved. Certainly, this was not universally the case. Several scholars had made vital inroads, including CODART members Christi M. Klinkert and Tanja Kootte. But on the whole, these prints, especially if they contained letterpress text, were often undervalued and understudied. In addition, when text-heavy prints (for example, broadsides by Romeyn de Hooghe) did get more attention from scholars, they were often reproduced with the text cropped off, showing only the image. This can skew people’s perceptions about how early modern prints look and reinforce the idea that text is not desirable or significant for these works. And yet, in early modern Europe such prints—their images and texts—shaped collective memory, played a part in coordinated propaganda campaigns, and caused even international incidents.

Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708), Marriage of William and Mary, 1677

Krannert Art Museum (inv. no. 2019-7-7)

The abundance and innovative quality of these prints had a great deal to do with the unique political organization of the United Provinces. The Republic had much to offer artists: an influx of wealth and innovative ideas from religious and political refugees; new knowledge, commodities, and revenue from global trade and exploration; new art genres and art markets; and more. But as a fledgling republic, the Dutch had limited means of effectively censoring political media, unlike neighboring monarchies in England or France. Printmakers exploited this unprecedented freedom to criticize leaders at home and abroad and to attempt to shape political policy and action. The decentralized nature of the Dutch government also led to chronic infighting between rival factions, as well as to international conflicts about sovereignty, trade routes, and territories. This volatility only provided more fodder for printmakers to create images, which numerous audiences relied upon to stay informed, celebrate victories and mourn defeats, and to stoke the fires of partisanship.

Printmakers of the period experimented with graphic visual language in a daring and subversive fashion. They supplemented conventions and tropes inherited from medieval and Renaissance maps, city views, book illustrations, news prints, and polemical prints and established new forms of expression. While some of their prints employ visual puns and humor that even the illiterate could enjoy, others were captioned in Latin, French, or German as well as Dutch, enticing educated elites across Europe to explore the relationship between text and image. Through mercantile and diplomatic channels, Dutch political prints transcended national and temporal boundaries to make a lasting impact.

Many of the political prints that Krannert Art Museum has amassed will feature in an exhibition tentatively titled “Fake News and Lying Pictures: Political Prints in the Dutch Republic,” which will be on view from August 26 to December 4, 2021 before traveling to other venues. The exhibition will include approximately 100 prints and illustrated books. They range from monumental engravings by celebrated artists to cheap broadsides, demonstrating that people across classes and throughout Europe participated in robust and sometimes violent debates by means of print media. The prints date from the late sixteenth century, coinciding with the onset of the Eighty Years War in 1568, to the early eighteenth century, with the death of William III in 1702. This was an especially rich period for political printmaking, with gradual, marked changes in the style, iconography, and viewership of these images.

Organized in six sections, the exhibition will explore the continuity and development of various tactics and themes used to picture political beliefs and events, from the late sixteenth century to the early eighteenth century. These include: Dutch Lions and Other Political Animals (animal satire); Founding Fathers/Fallen Fathers (murdered politicians); Spoils of the Seas (the Dutch East and West India Companies, seafaring, naval warfare, etc.); Face of the Enemy (foreign adversaries, war crimes, criminals); Men of Action/Women of Honor (Dutch men, women, and children); and Romeyn de Hooghe: Propaganda Master (arguably the most important political printmaker in seventeenth-century Europe).

The project has received a Getty Foundation Paper Project Grant, which will be used for international loans and the accompanying publication. The Paper Project is a multiyear initiative that seeks to enhance the training and professional development of early- and mid-career curators through support for workshops, seminars, symposia, fellowships, exhibitions, and publications. Given that many of the most rare and spectacular Dutch political prints can only be found in European museums, the Paper Project Grant will expand the scope and depth of the exhibition considerably. In addition, while the exhibition and its label copy will be intended for a general audience, the accompanying publication will be scholarly in nature and geared more toward researchers in the fields of early modern European art and history.

Jan Wierix (1549-c. 1620) after Crispin van den Broeck (1524-1590), Perseus and Andromeda; an Allegory of William of Orange Saving the Dutch Republic of Habsburg Spain, ca. 1577

Krannert Art Museum (inv. no. 2016-1-1)

You might wonder why Krannert Art Museum, a university art museum in the Midwest, would chose to aggressively collect this particular type of artwork. There are a number of factors at play. Like any museum, we aim to collect works that meet a high standard and are compelling to and relevant for various audiences. As such, aesthetic value and quality remain one of our considerations. Another factor is the potential for study. Because we are part of a larger research institution, the University of Illinois, our acquisitions and exhibitions are expected to generate new knowledge and be presented in a format accessible and useful to a wide range of visitors, from school children to university students and professors to members of the community. We strive to create exhibitions and programming that appeal to diverse departments across campus. These prints can appeal to students of history, law, political science, and others as well as the studio arts and art history. Another factor was the cost. The underappreciation of some of these prints makes them more affordable. In addition, my own expertise in this subject is another reason for KAM to collect this kind of print. Additionally, as a university art museum, Krannert Art Museum has more leeway to choose works of art that fall outside the traditional definition of “high” or canonical art. We enjoy the freedom to consider the margins of art history, as it has traditionally been told. Finally, these prints are attractive because they resonate so deeply with current issues. Their impact goes beyond the seventeenth century, to prefigure contemporary visual culture. Dutch printmakers used trolling tactics long before the invention of the internet; they concealed damaging information, told outright lies, and ridiculed public figures using an array of strategies akin to those of today’s cartoonists and sketch comedians. Their prints stoked collective unrest, scorn, and even violence for political gain—functions that images continue to serve.