On 12 September 2019, the Amsterdam Museum announced that it would no longer be using the term ‘Golden Age’ as a synonym for the seventeenth century because the term does not give an accurate representation of that century and creates a barrier impeding efforts to tell the history of that era in ways that are relevant to the entire breadth of the population of Amsterdam and the Netherlands at large. The decision prompted a tidal wave of reactions, some of them positive and some extremely negative. Among CODART members too, it is fair to assume that opinions will be divided. Curator Tom van der Molen of the Amsterdam Museum is pleased with his museum’s decision and has written an essay about his own relationship to the term “Golden Age.” He explains why he now no longer uses the term as a standard way of referring to the seventeenth century.

‘Our Golden Age: need I tell anyone what I mean by this? Is there a single cultivated Dutchman who does not know that those words can only apply to the period of our history that lies between the departure of Leicester in 1587 and the Peace of Utrecht in 1713?’

Such were the opening words of Pieter Lodewijk Muller (1842–1904) in the Preface to his monumental book on the seventeenth century in the Netherlands, Onze Gouden Eeuw – ‘Our Golden Age’ – in 1897. If I ask that same question today, over a hundred years later, I can still proceed on the assumption that most of my readers will immediately understand what I mean when I refer to the Dutch ‘Golden Age’. We still use the term without much thought. However, my museum, the Amsterdam Museum, has decided to stop using it. I am happy about this, since the term is not fit for purpose.

The phrase ‘Golden Age’ became fashionable in the nineteenth century, when history was being framed in a nationalist context that served to unite the nation. It emphazised pride in what were seen as periods of great prosperity and in the country’s heroes. Today, some two centuries later, expressions of pride in that period of power and wealth attract fierce criticism. Rightly so. The nineteenth-century monuments and street names that place that era and its protagonists on a pedestal have come under fire. The term ‘Golden Age’ as a designation for the seventeenth century is rooted in those same feelings of pride, but it also has a longer history, of course, and a wider spectrum of associations, than a particular period in Dutch history. The time has come to explore those associations and to ask ourselves why we still use the term. And whether we should continue to do so.

The Golden Age as a Description of the Seventeenth Century: Muller and Huizinga

The historian Muller whose words are quoted above was the first writer to use the phrase ‘Golden Age’ to express national pride: pride in the art as well as the military and economic power of this small country. It was a competitive pride: the Netherlands was presented as better than all other countries and even as a near-unique marvel in the history of the world:

‘It was when extraordinary intellectual development went hand in hand with unparalleled prosperity and rare vigour. The flowering and glory of Florence and Venice seemed to be combined in the Netherlands. One would have to go back to the mists of antiquity, to the Athens of Pericles, to find a comparable example of such wide-ranging development in such a small tract of land.’

Muller’s Dutch Golden Age, a period that witnessed the unprecedented, unique blossoming of power, wealth and cultural development in a small territory, was an important part of the way in which history was used to cement a sense of national identity. He therefore referred to it emphatically as ‘our Golden Age’ the heyday was our pride, our property, and part of the identify of every ‘cultivated Dutchman’. In other words, ‘Golden Age’ is a term devised to gold-plate Dutch national identity, to dress ‘cultivated Dutchness’ in a coat of excellence – indeed, superiority – with regard to all other nations. This means that ‘Golden Age’ is a term that automatically excludes certain people. If your ancestors did not share in the power and wealth of the seventeenth century, or were actually among the victims of the Dutch Republic’s efforts to increase its power and wealth, the term ‘Golden Age’ is at best irrelevant to you, and at worst a phrase that bristles with hostility.

Long before Muller, the eighteenth-century artists’ biographer Arnold Houbraken had also used the term, but with a far more limited frame of reference, to the period around 1650, in Amsterdam:

‘It was at that time the Golden Age of Art, and the golden apples (now scarcely to be found even through sweat and [by following] daunting paths) fell of their own accord into the mouths of Artists.’

Since Houbraken’s ‘Golden Age’ applied solely to artists, I did not see much harm in it. That artists were able to earn a great deal of money in that period seemed to me quite true, and even a little banal. But art history does not play out in a universe that is cut off from the rest of history. It is part of that context and intimately bound up with it. And once the scope of Houbraken’s remark is widened to embrace not just the arts and artists, but the entire history of the seventeenth century in Amsterdam or the Dutch Republic, you soon find yourself consumed by doubts as to whether ‘Golden Age’ is an apt term for that era.

In that more general sense, the term ‘Golden Age’ has never been uncontroversial. In 1941, when Johan Huizinga wrote his sweeping cultural description of the seventeenth century, he called it Nederlands Beschaving in de Zeventiende Eeuw (‘Dutch Civilization in the Seventeenth Century’). At the end of the book, he explains why he decided against using the term ‘Golden Age’:

‘It is the term Golden Age itself that is the problem. It evokes the Aurea Aetas, that cloud-cuckoo-land of Greek mythology that already made us feel a little uneasy in Ovid in our school days. If our heyday must needs have a name, let it be about timber and steel, pitch and tar, paint and ink, daring and piety, spirit and imagination.’1

According to Huizinga, then, the term ‘Golden Age’ is wrong because it misrepresents that century. It should be added that Huizinga by no means abandons his pride in that century. He goes on to assert that the virtues of the seventeenth-century Dutch – which he describes as their vigour, purposefulness, their sense of justice and fairness, their compassion, piety and faith in God – still characterise the Dutch in his own day. So, while he endorses the unifying goal of the historical account – ‘our age of prosperity’ – he states that the century cannot be called a Golden Age because his view of the seventeenth century was very far removed from the mythological example. It is quite true that Ovid’s Golden Age has nothing in common with the seventeenth century in the Netherlands: we must certainly agree with him here. In the Dutch Republic, criminal offences met with harsh sanctions, the country was more often than not at war, ships sailed to all corners of the earth to conquer territory and build plantations: in short, this was certainly no glittering, golden Arcadia. The term is not fit for purpose because it does not describe the historical reality.

The Golden Age of Recent Decades

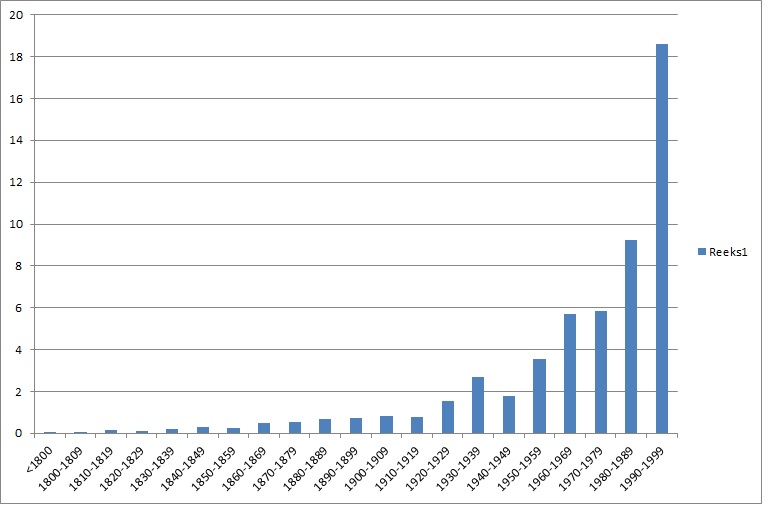

We can perhaps appreciate why the notion of a bygone ‘Golden Age’ was felt to be necessary in the nineteenth-century Netherlands, as a focus of national unity. It helped to bring cohesion to a relatively young nation state – the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Did the term come to be used less frequently, as the need to cement national identity became less acute? I searched the Dutch newspaper database Delpher of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (National Library) for uses of the term and calculated the frequency with which the term was used in each decade. Although the results are admittedly a crude yardstick, the figures reveal such a marked trend that it is fair to conclude that the term ‘Golden Age’ enjoyed a particular revival in the final decades of the twentieth century.

The frequency of the use of the term ‘Golden Age’ throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century in Dutch newspapers

Does this mean that Dutch people still feel a strong need for a national history to take pride in? Or have globalisation, migration, or even the abolition of the old compartmentalisation of Dutch society along religious or socio-economic lines reinvigorated the need, among part of the Dutch population, for a story that provides this measure of cohesion?

International trends suggest a different reason, since we find the term being used more frequently, in recent decades, in non-Dutch publications. Indeed, in Simon Schama’s Embarrassment of Riches (1987) we find one of the first uses of the term with a frame of reference beyond the confines of art. It seems that the ‘Golden Age’ has become above all a marketing tool, used to add lustre to the titles of exhibitions and books.

In the meantime, the use of this name has become so entrenched, for successive generations, that it has strongly influenced our picture of the seventeenth century. Even Ovid’s naïve dreamscape has left its imprint on that picture, since the Golden Age still has connotations of peace and a progressive ethical and moral ethos. The Dutch Golden Age is not traditionally discussed in terms of conquest, conflict and oppression: yet these are key characteristics of the period. Most writers opt to discuss the seventeenth century as an age of innovation, and moral and cultural superiority, as if trade naturally gravitated to Holland. Where conflict is discussed, the Golden Age narrative deftly casts the Netherlands in role of David versus Goliath. It depicts the waterlogged and diminutive Netherlands standing up to the great powers: first Spain, then England and France. By depicting yourself as small, you suggest that are not the aggressor and that you are fighting in self-defence against the ‘bigger foe’. Small size is suggestive of innocence – just like the people in Ovid’s Golden Age. That this leads to a distorted and incorrect picture of that century will be obvious.

The Golden Age Today

It will be clear that I have stopped using the term. Even so, I was confronted with my own routine use of the term when someone defaced the poster advertising the exhibition Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age, on show at the Hermitage Amsterdam since November 2014. It was a painful experience. Certainly not because I condemn the vandalism – the public space can be – must be! – a place where debate and communication take place, and protests cannot always remain within the letter of the law. Nor is it the case that I disagree with the message: I share (by now) the considerable sense of unease with the term ‘Golden Age’ and the associated – in my view misplaced – feelings of pride in Holland or Amsterdam. It was painful because I understand and endorse the message, but I was one of those who were responsible for the exhibition, including the title. I was one of the curators who organised that exhibition, and I have borne my share of responsibility for it for almost five years.

This poster on Zeeburgerdijk in Amsterdam was defaced. The title Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age was altered to read Portrait Gallery of the Stolen Age and the faces of the men depicted were obliterated.

In curating the exhibition Portrait Gallery of the Golden Age, we did dwell on the painful aspects of that century, but our well-meaning efforts at the time do far too little to truly challenge the narrative of pride in the wealth and power of the age, a narrative that remains quite dominant. I would never have arrived at this realisation without the criticism that has been levelled at us regularly over the five years of the exhibition. The criticism was sometimes difficult to digest, but it unquestionably did a great deal to raise our own consciousness. Personally, I am immensely grateful to people such as Leo Balai, Ida Does, Marian Markelo, Jörgen Tjon a Fong, and my colleague Imara Limon, who invited people to present their own vision of our exhibitions in their ‘New Narratives’ guided tours, and for quite radically transforming my picture of the seventeenth century. All are people of colour, who cannot share in feelings of pride in that century and who see those powerful, wealthy men and women as representatives of a system that abused and oppressed their ancestors and who traded in enslaved people. I knew these historical facts, but did not fully realise what they meant, since they relate to me in a different way.

Arie van Deursen begins his book on the seventeenth century De last van veel geluk (in which, like Huizinga, he avoids the term ‘Golden Age’) with a characterisation of history that rings true to me:

‘History does not prove, it tells. That is what the ancient Romans said. History is an endless debate. That is how the Dutch of the twentieth century saw it. Marcus Fabius Quintilianus versus Pieter Geyl. Who is right? It is a question with no answer. In an endless debate, right and wrong are always impermanent, and everyone can read their own message in a narrative. That is why we will always keep rewriting history.’2

I heartily agree. Every generation and every person must be given the opportunity to tell his or her own story about history and to interpret the stories told by others. But the debates about these issues require space – space for everyone. The name ‘Golden Age’ limits that space for many people who would very much like to take part in this debate. Ultimately, it creates a situation in which everyone loses out. And for that reason too, the term is not fit for purpose.

Tom van der Molen is a curator at the Amsterdam Museum. He has been a member of CODART since 2014.

[1] Johan Huizinga, Nederlands Beschaving in de Zeventiende Eeuw. Orig. Dutch edition Haarlem, 1941, pp 175–176 [transl. here Beverley Jackson].

[2] A.Th. van Deursen, De last van veel geluk: de geschiedenis van Nederland, 1555-1702. Amsterdam 2004, p. 9