This article was originally published in the CODART eZine, no. 7 Winter 2015.

John G. Johnson bequeathed his collection of 1,279 paintings to the city of Philadelphia in 1917. Among his primary interests were early Netherlandish and seventeenth-century Dutch paintings. Indeed, the Johnson Collection has over 425 early northern European paintings. When combined with the nearly 100 paintings that entered the museum from other sources, the Philadelphia Museum of Art hosts one of the largest collections of its kind in the world.

The size of the collection is imposing. Having only joined the museum in 2012, I am still very much in the process of discovering its treasures. This task is made more difficult by the lack of a current catalogue of the early northern pictures. Peter Sutton produced a magisterial catalogue in 1990 of all the northern paintings in the museum’s permanent collection, excluding those in the Johnson Collection. The latter were catalogued early on, in 1913 and 1914, by Wilhelm Valentiner, who advised Johnson on his purchases. Barbara Sweeney updated his catalogue in 1972, and hers is an exercise in brevity. Readers find only dimensions, inscriptions, published references and provenance. Well, I should say that each picture has a section labeled ‘provenance’. Many entries identify the provenance as ‘unknown’, ‘completely unknown’ and ‘entirely unknown’, without clarification as to what distinguishes an unknown provenance from entirely unknown one. And no discussions, interpretations or other forms of analysis are offered. As a result, the 1972 catalogue serves primarily as an illustrated checklist. Furthermore, it is pushing 50 years old at this point. Many attributions were updated for the concise catalogue of the European and American paintings in the museum’s collection that was published in 1994. However, that is merely an illustrated summary catalogue, and is itself over two decades old now.

A long line of distinguished curators at the museum have focused on the northern European paintings, among them Peter Sutton, Katie Luber, Larry Nichols and Lloyd DeWitt. Fortunately, their research and insights are reflected in the collection files. While this information is not readily accessible to others, the accumulated knowledge in those files has been a tremendous resource for me as well as for visiting scholars. Even so, due to the great size of the collection there remains much to do. The following remarks sketch some recent advances in studying the Johnson Collection; ideas for progress beyond these recent projects are also included.

Fig. 1: Copy after Hieronymus Bosch, The Adoration of the Magi (After the center panel of a triptych in the Museo del Prado, Madrid), early 16th century, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art

The museum can count 11 Boschian paintings among its holdings, all but one of them in the Johnson Collection. Unfortunately, the best of the lot, The Adoration of the Magi (inv. no. 1321), is also the one in the poorest condition (fig. 1). In preparation for the exhibitions in the Noordbrabants Museum and the Museo del Prado marking the 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death, we have undertaken a full conservation treatment. After removing layers of discolored varnish and later campaigns of in-painting, the picture offers opportunities for fresh appraisals. The paint surface was abraded, significantly in some passages, but much of those passages, including the figures, remained in good condition. The standing, forward-facing magus on the right, for example, is well-preserved and extremely fresh. The lively facial expression and confidently assured execution suggest the hand of the master. The opportunity to see it alongside the other paintings in s’Hertogenbosch and Madrid will present a chance to reconsider its attribution.

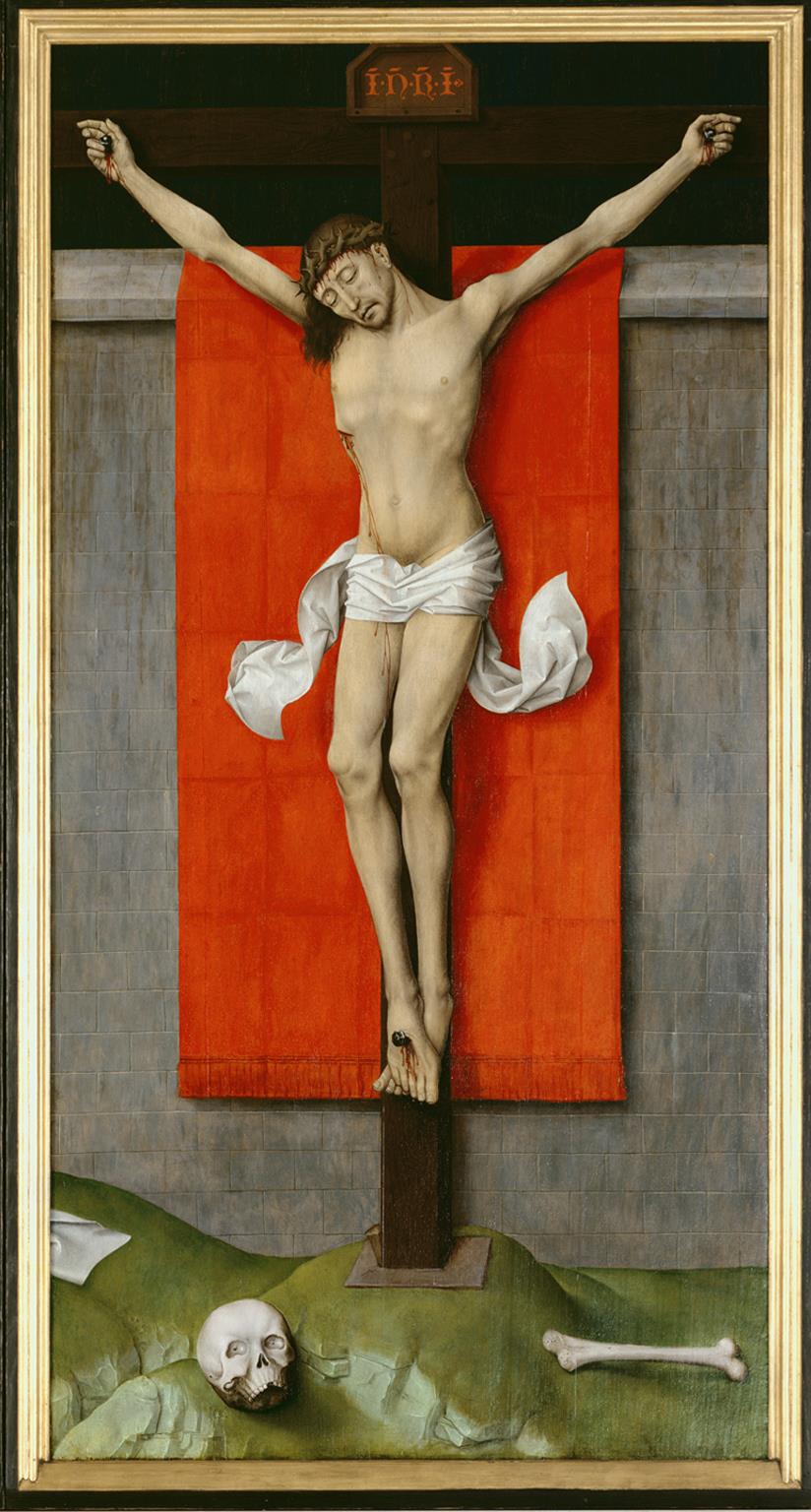

Although not on show in Madrid, the Philadelphia’s great Rogier van der Weyden panels (cat. nos. 334 and 335) have also been the subject of recent exhibition-related research, this time for the monographic exhibition of the artist’s work in the Prado (figs. 2 and 3). Mark Tucker, The Aronson Senior Conservator of Paintings and Vice-Chair of Conservation at the museum, and Griet Steyaert co-published a provocative essay on the panels and the ensemble of which they were a part in the most recent Boletín del Museo del Prado. This essay argues that the panels in Philadelphia originally formed part of the exterior of a carved altarpiece. It also presents the case for the identification of the reverse of the Philadelphia works. Steyaert identified paintings now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., as coming from the backs of the Philadelphia panels and thus being the far left and right panels of the open interior. In preparation for this essay, I happily studied not only our paintings but also the cited example in Washington, together with Tucker and Steyaert. We reviewed the relevant images and IRRs of all manner of Rogierian panels together as well. As significant as their findings are as regards original function and context, they merely open the door to further research into the components of the proposed painted and sculpted ensemble.

- Fig. 2 and 3: Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464), The Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning , c. 1560, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Fig. 2 and 3: Rogier van der Weyden (1399-1464), The Crucifixion, with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist Mourning , c. 1560, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art

This past spring we completed a reinstallation of our gallery devoted to small-scale fifteenth-century early Netherlandish paintings. In the new presentation we use Jan van Eyck’s St Francis Receiving the Stigmata (cat. no. 314) as a focal point and interpretive anchor (fig. 4 and fig.5). In so doing, thanks to an interpretation grant from the Kress Foundation, we built an interactive touchscreen that presents information on the subject, style and impact of the painting, as well a pinch and zoom feature that enables deep exploration of the picture’s minutely detailed surface. In total, the touchscreen enables us to present far more information than is possible on a label or dive card, while also allowing visitors to explore the subjects that interest them most. The topics and themes explored in the interactive are then continued in the labelling of other objects in the gallery, so that the entire installation coheres.

- Fig. 4: Jan van Eyck (1390-1441), St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata , 1430-1432, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Fig. 5: Jan van Eyck’s St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata in the gallery

Though the reinstallation and digital interactive have been geared primarily to general visitors, the project has reinvigorated our scholarly research into St Francis. We reexamined the publications issued on the occasion of 1997 exhibition that united the picture in Philadelphia with the version of the subject now in the Galeria Sabauda in Turin. As exhaustive as this study was, new questions have arisen. We very much hope to conduct new scientific examinations and documentations of the Philadelphia and Turin paintings together in the not too distant future. Likewise, I intend to investigate more deeply the support for the Philadelphia picture. Unlike the one in Turin, which was painted in oil on panel, it is in oil on vellum mounted on panel. This is not a later mounting, as the panel has been shown to have been cut from the same tree as that of the two portraits by Van Eyck now in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. Indeed, preliminary research suggests that such painterly experimentation with oil and other paints on vellum mounted on panel explored the boundaries and intersections between panel paintings and illuminations and, further, that this medium was particularly vital during the first half of the fifteenth century in the Burgundian Netherlands. Indeed, the museum has a related picture by Simon Marmion that was painted in tempera on vellum mounted on panel (fig. 6). I very much look forward to investigating the techniques and motivations for this overlooked pictorial phenomenon.

- Fig. 6: Simon Marmion (1420-1489), Pietà , late 15th century, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Fig. 7: Copy after Johannes Vermeer, Lady with a Guitar , late 17th century, John G. Johnson Collection, 1917, Philadelphia Museum of Art

The storage depot of the museum’s collection of European paintings, including the Johnson Collection, contains many unsolved mysteries. Among those that intrigue me the most is the Lady with a Guitar (cat. no. 497), which follows Vermeer’s painting in Kenwood House (fig. 7). The Philadelphia picture almost exactly reproduces the Kenwood one with the exception of the woman’s hairstyle. Johnson acquired the picture as a Vermeer but it was gradually removed from the artist’s accepted oeuvre over the course of the twentieth century. The painting’s compromised condition prevents its installation and exhibition. As a result, few current specialists have actually seen it in the flesh, and it has only been reproduced with black-and-white photography. Pigment analysis also banned it from the oeuvre. An old study seemed to have identified Prussian blue, but more recently that has been dismissed as a false positive. The same study also found the presence of lead-tin yellow, so it seems that the Johnson picture was completed before 1715, making it an extremely early, and rare, variation on Vermeer. Indeed, early copies and reproductions of Vermeer paintings are rarer than are paintings by the master himself. I look forward to pursuing whether any further insights into the authorship of the painting can be made.

For now, at least, we are operating on a case-by-case basis. There are no immediate plans for a systematic catalogue, although such a project is certainly merited by the unexplored riches of the collection. I am hoping, however, that the upcoming centennial of the Johnson Collection in 2017 will offer some additional opportunities to dive in more deeply. We are in the process of developing our plans to mark the occasion, but I hope that we can devise a framework for presenting more collection information online in addition to sharing research into specific case studies.

Christopher D.M. Atkins is Agnes and Jack Mulroney Associate Curator of European Painting and Sculpture before 1900 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He has been a member of CODART since 2012.