In recent years a number of American museums have shifted their collecting priorities to reflect the need to diversify their collections. Two CODART curators, Robert Schindler, Fariss Gambrill Lynn and Henry Sharpe Lynn Curator of European Art, Birmingham Museum of Art, and Lloyd DeWitt, Chief Curator and Irene Leache Curator of European Art at Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum of Art, report on new acquisitions that reflect these new priorities.

Tell us a little bit about your institutional situation that forms the backdrop for this acquisition and your desire to diversify your collection?

Robert Schindler: The Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama is one of the largest encyclopedic art museums in the Southeast United States. Founded in 1951 as a department of the City of Birmingham, the museum is located in the historic city center with the town hall (built 1950), the courthouse (1932), the library (1927), and the municipal auditorium (1924) all bordering on a small public park. Until earlier this year, a confederate monument stood at the park’s most elevated point. The museum opened during the Jim Crow era, when Black residents were systematically disenfranchised and disadvantaged, including at the museum. The museum was only integrated in 1963. Today, the city’s population is over 70% African American, and communities in the city are still largely segregated.

While a more diverse staff has joined the museum in recent years, its staff is still predominantly white; its leadership team and the curators are all-white. Historically, especially Black communities have felt unwelcome or unsafe at the museum and that its collection, exhibitions, and programming had little to offer them. In recent years, the museum has begun a concentrated effort to change this and to work more closely with and for the local community. Diversifying our staff, building trust and patronage, and refocusing our public offerings will be a long process that requires our full commitment.

Lloyd DeWitt: Like the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Chrysler Museum of Art is a municipal art museum that has its roots in the period of segregation. Located at the water’s edge in Norfolk, Virginia, it formally opened to the public during the Great Depression in 1932 as the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Science. Its small group of European art objects were donated by Irene Leache and Annie Wood, two teachers and friends who had run an unusual school for girls that taught classical subjects. Walter P. Chrysler Jr.’s astounding 1971 gift of over 25,000 works of art expanded the museum into an encyclopedic art museum including African, Asian and Mesoamerican art. While he succeeded in challenging local sensibilities by installing a portrait of General Grant in the museum, the museum still had almost no images of Black people, and few works by Black artists.[1]

What did your museum acquire, why, and how did the acquisition process unfold?

Fig. 1. Juriaen van Streek (1632-1687), Still Life with Male Figure, ca. 1650-1680

Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL, USA

RS: Diversifying the museum affects our institution on many levels, including acquisitions. The European collection is installed front and center when entering the museum. Histories of people of color, non-Western perspectives, and colonialism were until very recently virtually absent. This is due both to what the museum has historically chosen to acquire, as well as how we chose to present the collection. In 2018, the museum acquired a still life by Juriaen van Streek (fig. 1) to begin remedying the shortcomings of the collection to tell these stories. The painting shows an arrangement of foreign fruits and valuable objects on a table behind which stands a man dressed in fine, embroidered clothes and wearing a gold earring. He is looking out at the viewer while holding a glass, as if drawing our attention to it. The artist took great care in describing the individual features of the figure, and most likely an actual person modeled for the artist. It is possible, if not likely, that he was a servant and perhaps a enslaved person in anything but name, as slavery officially did not exist in the Dutch Republic proper. Van Streek specialized in still life paintings, several of which include a Black man. But no information seems to survive that could illuminate who this person was or what his lived experience was.

The painting was offered at TEFAF Maastricht that year but remained, surprisingly to me, unsold. Its potential relevance for the museum was immediately apparent: making visible people whose existence and histories have otherwise been erased. However, given limited acquisition funds and the attribution to a little known Dutch painter, I was initially hesitant. After consulting with curatorial colleagues, the Chief Curator, as well as the museum’s Director, we agreed that we wanted to pursue this and began our standard acquisition process. In this case, it included revisiting our traditional acquisition criteria. Particularly, more weight was given to the opportunity the object would present to expand the narratives we explore in the presentation of our collection. Both our staff as well as the members of the acquisition committee were supportive. Some discussion concerned finding an appropriate funding source; in the end, a single-donor fund was used with the patron’s permission. We eventually reframed the painting and included glazing to better protect it from environmental changes and any physical damage.

Fig. 2. Abraham Teniers (1629–1670). Guardroom Scene with African Soldier Cleaning Pistols, ca.1650–65

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, USA

LD: In March 2019 the Chrysler Museum of Art was offered a guardroom scene attributed to David Teniers the Younger (1608–1680) (fig. 2). While Teniers and his workshop produced a large number of such scenes, this one stood out because the central figure was a compelling portrait of a Black man cleaning pistols, and the composition appears to be unique in Teniers’s oeuvre, a body of work which features a great deal of repetition and reuse of his inventive and popular genre motifs. After it failed to sell at auction, the museum was able to acquire this work, an intriguing panel and a rare European painting to prominently feature an African man.

In this composition the soldier looks out directly at us, interrupted while cleaning the gun. He wears an oversized plumed hat and light undergarment, and has bare feet. He is surrounded by arms and armor, flags and drums while in the background other soldiers (one in armor) gather in a tavern-like guardroom space to drink, sleep and gamble. All these characters evoke the many kinds of foreign mercenary soldiers that were a consistent presence in the Netherlands during the long war between the Protestant Northern provinces and Spain.

Once the painting was acquired, Mark Lewis, Senior Conservator, undertook its cleaning, which uncovered a work of considerable brilliance, and also revealed that the face of the man was painted with a directness, sensitivity and using a dashing stroke that stood out from the rest of the work, forcing us to revisit the attribution question. While the rest of the painting is consistent in style with works signed by and attributed to his studio assistant and younger brother Abraham Teniers (1629 – 1670), this key detail may be by David the Younger! Pierre Terjanian, head of Arts and Armor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, kindly suggested that the bare-legged African man did not wear armor. While the portrait seems taken from life, the painting intriguingly echoes the theme of the fictional c. 1610 play The Valiant Black Man in Flanders by Spaniard Andres de Claramonte, a work of fiction that nevertheless validates the presence of black people in the Spanish Army in Flanders as Teniers depicted.

This was a highly unusual opportunity to acquire a 17th-century genre work from Flanders with a beautiful portrait of African man, and one that shows him in an active role. The acquisition process was partly guided by the advice of a community advisory committee to the Chrysler Museum’s 2018-2019 exhibition project Thomas Jefferson, Architect. This group of community leaders helped guide the interpretation and content of that exhibition around the subject of slavery. They advised focusing on works of art that illustrated and demonstrated the work and creativity of Black people, a principle that has been incorporated into the collection strategy of the European Art department.

How is the museum integrating these paintings into the galleries?

RS: The painting is now on display in the museum’s gallery dedicated to Dutch and Flemish art, where it is the only object relating to the presence of Africans or people of African descent in the Republic or more broadly the Dutch colonial enterprise. Drafting the gallery label that accompanies the painting was a lengthy process that involved a deep and productive collaboration between several education and curatorial staff. Staff brought their personal experiences and expertise to this process. However, external expertise or community involvement was not sought in a structured way at this point mainly because the necessary relationships and mechanism were not in place yet. Concerns included: how to appropriately account for the complex histories and experiences of Africans in the Netherlands and the Dutch involvement in the slave trade; how to navigate the unique weight resting on this painting and its accompanying text given that it would be the only object and gallery text in which colonialism was addressed in the European galleries–at least for the time being; the need to acknowledge the continued impact of this history of colonialism, slavery, and systematic violence against Africans and people of African descent has on the lives of people today; how to address the fact that we can only speculate what the lived experience of the man in the painting was; and how to give the man depicted in the painting, as well as its viewer, agency. We have so far not systematically captured visitor’s feedback to the painting or its presentation.

-

Fig. 3. Salvator Rosa (1615-1673), The Baptism of the Eunuch, ca. 1660

The Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, USA. Gift of Walter P. Chrysler, Jr.

-

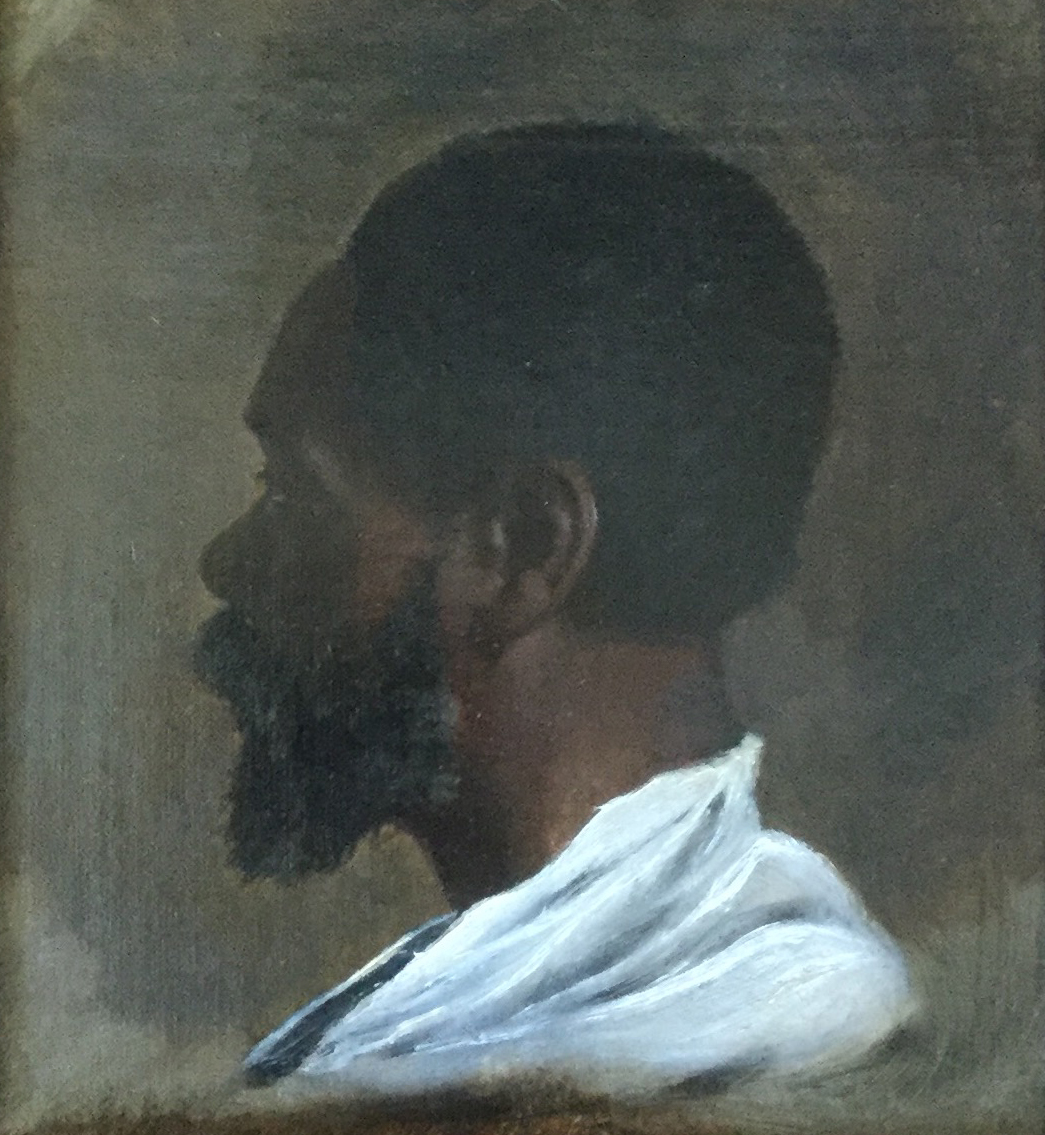

Fig. 4. Thomas Mervyn Bouchier Marshall (1830 – 1859), Portrait of a Black Man in Profile, presumably Zeno Oreno, ca. 1850-55

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA, USA

LD: This new acquisition joins the Italian Baroque artist Salvator Rosa’s remarkable Baptism of the Eunuch, in which the apostle Philip meets a representative of the nearly contemporary work featuring two dignified African male figures, the eunuch emissary of Queen Candace of Ethiopia (identified as Kandake Meroe of Kush, d. 10 CE) and his youthful servant page or servant, at its center (fig. 3). More recently the Museum has acquired an intriguing small portrait of a free black man, possibly the Guadalupan traveler Zeno Oreno, painted by the British artist Thomas M. B. Marshall c. 1850 (Fig. 4). The museum is also embarking on a plan to decolonize and reinstall its European art using a highly collaborative process involving all parts of the museum team, and in consultation with its IDEA committee. Guided by its strategy document the Chrysler continues to diversify its European collection by adding artists and subjects of color and bolstering the small group of works by women artists.

RS: The acquisition of the Van Streek is part of a reimagining of the European art department and the museum as a whole, as well as a reckoning with the erasures that have occurred within this institution. Much work still needs to be done. This will also include revisiting who partakes in these processes, how decisions are made, and who is making them; these questions were not sufficiently addressed at the time. Change is happening but diversifying the collection will take time. Thankfully, there is a lot of buy-in at my museum for this change. It is a long road, so to speak, and yet one that we can’t travel on fast enough.

[1] Following the recent decision of the New York Times and hundreds of other American media institutions, in this article we capitalize Black. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/05/insider/capitalized-black.html. https://apnews.com/article/7e36c00c5af0436abc09e051261fff1f

Robert Schindler is Fariss Gambrill Lynn and Henry Sharpe Lynn Curator of European Art at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Birmingham, Alabama, USA. Lloyd DeWitt is Chief Curator and Irene Leache Curator of European Art, at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, USA.