CODART members have many things in common. For instance, we all undoubtedly have a copy of the Diary of His Journey to the Netherlands by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) on our bookshelves. This personal journal by one of the great masters of art history, documenting his travels through the Netherlands – the art he saw, the festivities with which he was welcomed, and his meetings with prominent public figures and many other artistic virtuosos – has an irresistible appeal to the imagination.

The notebook was not in fact intended to serve as a diary. It was a factual description of the route Dürer followed, his ports of call, the stock of prints he kept and sold, and his income and expenditure. Occasionally he added particulars relating to art or artists, or very brief artistic critiques. This means that the journal enables us to reconstruct the practical details of his journey as well as providing some unique reflections on his fellow artists. This journey is the subject of the exhibition Dürer was Here: A Journey Becomes Legend, which was on view at the Suermondt Ludwig Museum in Aachen until 24 October 2021, and is now travelling to the National Gallery in London.[1] The exhibition provides an opportunity to trace Dürer’s steps, not just lingering in the cities he visited and dwelling on his diverse encounters, but also following his intellectual and artistic development. The show confirms once again that this journey was of inestimable influence on the art in the Low Countries and Dürer’s art.

It was at the end of 1519, after the death of Emperor Maximilian I, that Albrecht Dürer embarked on this journey, together with his wife Agnes and maidservant Susanne. The Emperor had awarded Dürer an annual pension of 100 Rhenish guilders in 1515, which lapsed after his death. Dürer hoped to safeguard his pension by attending the coronation of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in Aachen Cathedral on 23 October 1520. The first room of the exhibition presents the faces of the political protagonists to whom he addressed himself in his career. Their favors helped to secure the unique status that the Nuremberg artist enjoyed during his lifetime.

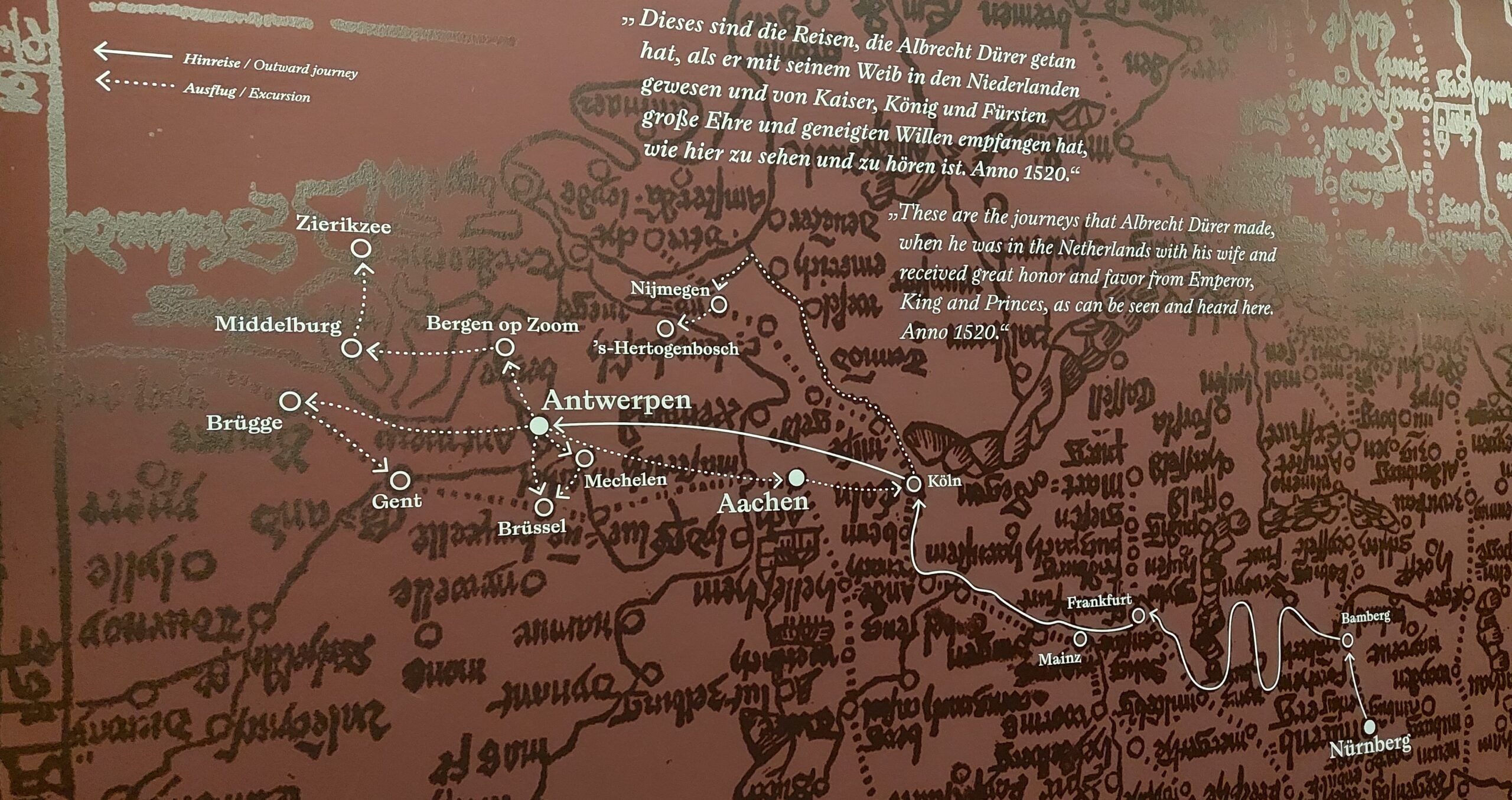

Dürer’s route through the Low Countries, as displayed in the exhibition in the Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum in Aachen

The obligatory visit to Aachen was the start of the journey around the Low Countries that would take up an entire year. He travelled by way of Cologne to Antwerp, which served as a base for visits to cities including Nijmegen, s’-Hertogenbosch, Ghent, Bruges, Middelburg, and Brussels. In the nineteenth century, the travel journal inspired artists to depict scenes showing Dürer soaking up the art and customs of the Low Countries. Displaying these works helps to peel away the layer of historical over-interpretation of the travel journal, after which the influence of the journey is assessed with more nuance, on the basis of source material. All but a few pages of the original journal have been lost, but the copy made around 1550, which is preserved in Nuremberg State Archives, is part of the exhibition. A second copy, from Bamberg State Library, can be accessed and browsed online in the show.

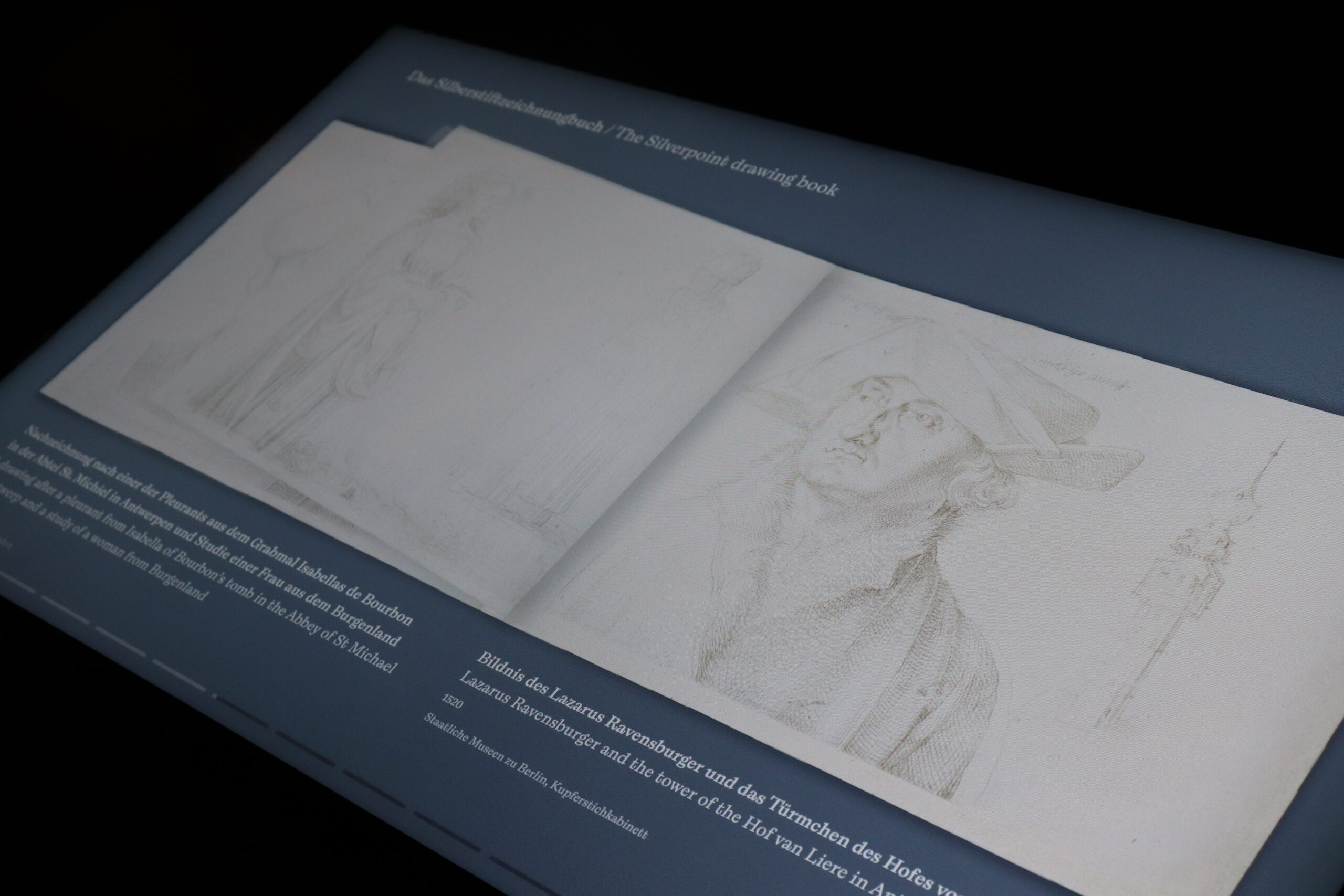

The second part of the exhibition focuses on the artworks – primarily drawings – that Dürer produced in the course of his journey. We get to know an artist who registers everything that fascinates or appeals to him in pen and brown ink: Antwerp harbor, the Zoological Gardens at Coudenberg Palace, the exuberant winter clothing worn by Livonian women, the head of a stuffed walrus, the Deposition by Jan Gossaert in Middelburg (new attribution), a lion, a dog, cityscapes, and so on. He worked in a sketchbook with prepared paper, wielding his silverpoint with dazzling skill. This sketchbook has been digitized. You can browse it in digital form in the exhibition, which will give you a sense of looking over the master’s shoulder during the process of artistic creation.

That Dürer also set his sights on producing an artwork for Margaret of Austria, Governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, is clear from a series of preliminary studies for a Virgin and Child Surrounded by Saints. As far as we can see, this was Dürer’s only artistic setback on his journey, since he was unable to interest Margaret in his designs, which therefore never progressed beyond sketches.

An impressive portrait gallery in charcoal bears witness to encounters with people from all walks of life. His working method, style, and the scale of his portraits were all innovative – these drawings are end products. Dürer used the money earned from sales of these portraits and his prints to finance his journey. His was a highly unusual way of working, which only Lucas van Leyden would dare to emulate. One of the portraits in this room does not belong to this series, but nonetheless merits particular attention. That is the portrait of 20-year-old Katherina, which is elaborated with marvelous subtlety and delicacy in silverpoint. This is the first portrait of a black woman in Western art history.

A series of painted portraits of Dürer’s fellow artists from the Low Countries gives an impressive overview of the state of portraiture at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Although Dürer was influenced by Netherlandish art, the main thing to emerge from this series is that the great German master did not allow the work being produced to the west of his country to influence his portraiture. Influence in the opposite direction is clear, however, in the series depicting St Jerome in his study. The model for this painting was a 93-year-old man, who according to the journal was paid three stuyvers for posing. A copy of the portrait drawing and painting are shown together in the exhibition. Works by Joos Van Cleve, Lucas van Leyden, Jan Sanders van Hemessen, and Marinus van Reymerswale demonstrate the influence of this important composition.

Dürer’s St Jerome of 1521 from the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga in Lisbon and a copy by Hans Hoffmann of Head of a 93-year-old-man from the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford

This series is a perfect segue into the final theme of the show, which demonstrates the great influence of Dürer’s prints. While his imitators repeated the compositions he had produced in many different media, Dürer also encouraged artists to branch out and explore other media. For instance, Jan Gossaert was led by his admiration for Dürer’s prints to take his first tentative steps in printmaking. Lucas van Leyden, on the other hand, was locked into constant competition with his German counterpart.

The exhibition concludes with the many imitations of the large Calvary that Dürer designed in 1505. The scene was not innovative, yet several important artists such as Lucas van Leyden, Pseudo Jan Wellens De Cock, and Jan Breughel the Elder, copied part or all of it – undoubtedly because Dürer was so well known.

Organizing an exhibition like this amid a global pandemic is no mean feat. Although the museum was obliged to postpone the project for a whole year, in the end only one loan had to be withdrawn. The extra year was used to publish a new, scholarly standard work on Albrecht Dürer, which explores, analyzes and re-emphasizes the journey’s enormous impact. In accordance with this vision, the exhibition provides an in-depth picture of the exchange of artistic ideas at the beginning of the sixteenth century, supported by carefully-chosen masterpieces. About a great master such as Albrecht Dürer there is always more to say. It is an endlessly fascinating subject, and it is fortunate that the show is now travelling to the National Gallery, London.

[1] The London exhibition Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist (20 November 2021 – 27 February 2022) extends to cover the influence of all the artist’s travels around Europe.

Anne van Oosterwijk is Director of Collection at Musea Brugge in Bruges. She has been a member of CODART since 2007, and a member of the editorial board of CODARTfeatures since 2020.